- Facebook54

- LinkedIn4

- Threads4

- Bluesky3

- Total 65

Crime’s power as a political issue is troubling.

On one hand, the US experiences far too much crime. Our homicide rate is almost five times that of Britain, almost three times that of Canada, and 17 times that of Japan.

On the other hand, crime rates have tended to fall in the USA since 1992, and today many people assess crime as much more pervasive than it is. Many voters seem to have the idea that urban communities were safe earlier in their own lifetimes but are now very dangerous, even though crime rates were distinctly higher in the late 20th century, and most urbanites are doing fine today. This belief motivates reactionary and authoritarian policies.

An obvious explanation for the mismatch between public opinion and trends is … the media. If it bleeds, it leads. Some major news sources evidently want to fuel hostility to migrants, people of color, and cities by relentlessly presenting crime. And politicians, such as the current president, amplify the media’s attention to crime.

In 2016, the Cooperative Election Study (now housed at Tisch College!) fielded an extensive battery of questions about crime. As one might expect, whether respondents viewed crime as a very important issue was related to which kinds of news they watched. The percentage who rated crime very high was 52% among local news viewers, 49% among national TV news viewers, 49% among readers of print news (which usually means a local newspaper), 34% among readers of an online news source, and 45% among those who followed no news at all. These differences are not very large but would probably expand if we compared specific outlets, such as Fox News versus the online New York Times.

However, it is always worth trying to put media effects in context. No one has to watch Fox News or the local TV news; that is a choice. Media effects probably connect to other factors, such as demographics and values, in a complex system that has no single “root” cause.

I am not an expert on this topic, but I wanted to get a rough handle on it, so I ran a regression using the 2016 CES data. This method purports to predict how highly people will rate crime as an issue based on a set of variables taken together.

For example, I included both whether a person was a victim of crime in the last four years and their education level. We know that people with less education are more likely to be victimized, but a regression disaggregates such relationships so that you can see how much education matters regardless of whether people are victimized by crime, and vice-versa.

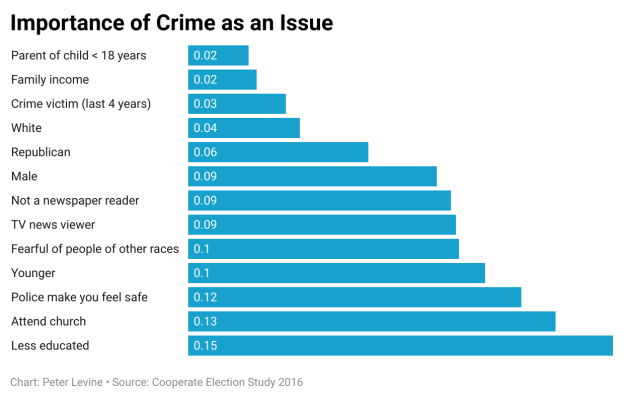

The results are shown above and can be explored a bit more here. The units are standardized Betas, a measure of how much each factor matters compared to the others. All the results are statistically significant at p <.05. I had included two variables in the model that I omitted from the graph because they were not significant (social media use and approval of the local police department).

Most of the patterns are intuitive. People are more likely to view crime as a major issue if they are white, Republican, male, less educated, and willing to admit that they fear people of other races. Watching the TV news is related to greater concern about crime, even when considering the other factors separately. And reading a newspaper is related to less concern. Younger people, parents, and richer people are more concerned.

The whole model is not very predictive, explaining only 16% of the variance. That is interesting in itself, suggesting that these factors–including TV viewership, race, and partisanship–do not really explain what is going on. Perhaps more depends on which specific channels and social media accounts people watch–but that would have to be shown.

(The labels on the graph suggest that these are binary variables, e.g., either watching TV or not watching it at all. But the questions were multiple-choice scales, so the labels are really my shorthand.)

See also: what voters are hearing about in the 2024 election; what must we believe?; civic responses to crime; and more data on police interactions by race