Yuval Levin offers an important perspective on the second Trump Administration so far.* I anticipate several reasons that Trump opponents will be skeptical, but I think that Levin’s argument should influence the strategies of the left and the center-left.

Levin’s key points:

- “Trump signed fewer laws in this first year of his term [2025] than any other modern president, and most of these bills were narrow in scope and ambition. The only major legislation was a reconciliation bill that contained a variety of provisions but was, at its core, an extension of existing tax policy.”

- Trump has signed fewer regulations of economic significance than Clinton, Bush, Obama, or Biden had by this point in their presidencies. Of course, regulations can have significance that is not economic, but this measure (from the Regulatory Studies Center at George Washington University) has the advantage of roughly distinguishing between important regulatory changes and documents that may be purely symbolic or even trivial. Based on this method, it appears that Trump has done less with regulations than his predecessors so far.

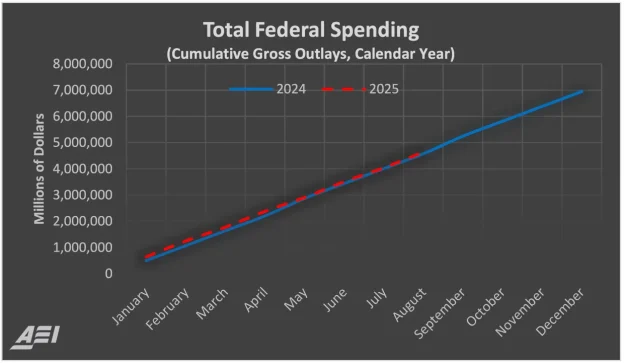

- As shown in the graph above, federal spending has been very similar as it was under Biden. It’s true (as Levin shows) that Homeland Security has more money and Education has somewhat less. But the reduction in Education seems to reflect planned sunsetting of COVID relief payments. In some cases, there were dramatic announcements of spending cuts (which may have caused substantial immediate damage) followed by a quiet resumption of spending. This seems to the case, for example, at NIH.

- Many federal employees were laid off, and many quit, for a total of about 317,000 “departures.” This matters to those people, to the capacity of federal agencies, and to the quality of public service right now. But since the positions are still authorized in law, it also means that the next president will be able to hire hundreds of thousands of civil servants.

- Trump has announced dramatic deals with various private entities, such as law firms, universities, and pharmaceutical companies. These deals raise serious constitutional questions and may intimidate other entities. Alas, there has been a lot of cowardly preemptive compliance. At the same time, these deals often turn out to be less consequential than they sound at first; and to a significant extent, everyone else in these sectors is proceeding as usual. Battling selected opponents makes great symbolic politics but is not an effective way to change a society. Levin says, “this approach of deal making has definitely expanded the distance between perception and reality. It has created an impression of an enormous amount of action when the real amount is — not zero, by any means. But we’re living in a less transformative time than we think in this way.”

Important caveats are required, and Levin acknowledges most of them.

First, immigration appears to be a major exception. Money is flowing to ICE, agents are being hired, and individuals and communities are being irrevocably harmed by tactics that are new or at least substantially worse than under Biden.

Second, Trump’s abuse of the Department of Justice to harass enemies is not captured on the list above.

Third, Trump style of governance may permanently change our political culture. His abuse of prosecutorial power is an important example.

Fourth, we don’t know what will happen next. Trump has won the power to replace members of regulatory commissions. Maybe these replacements will begin to enact actual regulations that matter.

Finally, his strategy may not be to change policies but to set the conditions for what Ezra Klein calls “power consolidation.” For instance, the right question may not be whether Trump’s tariffs have changed the economy. Rather, by levying tariffs at will and then excusing selected industries, countries, and firms from some tariffs, Trump has amassed power. This matters if–and to the extent that–he then uses his consolidated power for tangible purposes, such as suppressing the political opposition.

Using his power to protect himself is possible but will not be easy for Trump to accomplish. For example, his effort to interfere with the 2026 election by cajoling state legislatures to gerrymander may have produced a net Democratic advantage of about 2 or 3 seats.

Backlash to Trump may create opportunities to rewrite the rules in ways that curtail future presidents. ICE was already problematic under previous administrations. Migrants often present opportunities for governments to to abuse power. Hannah Arendt says that when World War I left a wave of stateless refugees, governments empowered their police in ways that led to dictatorship: “This was the first time the police in Western Europe had received authority to act on its own, to rule directly over people; in one sphere of public life it was no longer an instrument to carry out and enforce the law, but had become a ruling authority independent of government and ministries.”** This passage is eerily reminiscent of ICE in Minneapolis right now. However, the US public’s turn against ICE has been dramatic, and the current structure is now entirely dependent on Trump or a MAGA successor. It is quite plausible that ICE will be abolished in 2029 or at least much more constrained in then than it was in 2020.

Here are some strategic implications of Levin’s argument.

Don’t be tempted to emulate Trump. I’ve talked with progressives who basically say, “I hate Trump’s values and goals, but he has shown us how to make change.” Levin suggests that Trump is not making sustainable or coherent change. Indeed, he is making much less tangible policy than Biden did. If you want to shift the country, there is no alternative to passing actual laws.

Work against preemptive compliance. Trump’s retail deal-making doesn’t affect the society as a whole except insofar as organizations pre-comply out of fear that he will turn to them next. All of us who have stakes in organizations must buttress their independence and press them not to acquiesce in advance.

Plan for governing when Trump is gone. For example, how should the next administration fill more than 300,000 vacancies with young talent? Now is the time to plan for that. The statutory and regulatory framework that existed under Biden may still be largely in place, offering many opportunities for hiring and spending (even if total federal outlays are trimmed).

Focus resistance on the areas where Trump is actually effective. The top of that list is immigration, and I think most of the resistance realizes this.

Bear in mind that most citizens may not see much change. Progressives are rightly alarmed about Trump and often frustrated that the electorate does not see him as we do. Trump’s popularity has declined, but the rate of decline has been less than one percentage point per month. Voters may be turning gradually away from him because they perceive high inflation, which is not a wise basis for assessing Trump or any president. One reason that low-attention voters are not more critical of Trump is that their actual lives have not changed dramatically due to the Administration. At a meeting that I attended in the industrial Midwest last fall, grassroots activists (almost all Black and urban) viewed their community’s problems as perennial and unrelated to Trump. This has implications for how the opposition should criticize Trump–not by claiming that the president has wrecked everything but by accusing him of failing to act effectively.

*Levin, “Status Quo or Revolution?” The National Review, Sept. 25; interview with Ezra Klein, “Has Trump Achieved a Lot Less Than It Seems?,” Jan 16; and “The Levers Trump Isn’t Using,” The Atlantic, Jan 20.

** Arendt, Hannah. The Origins Of Totalitarianism (Harvest Book Book 244) (p. 287). (Function). Kindle Edition. But the public backlash to ICE under Trump has been extraordinary. As part of the reaction, the federal government may be pushed back out of immigration enforcement.