- Facebook177

- LinkedIn2

- Threads1

- Bluesky2

- Total 182

There is a huge body of research that suggests that people are not very susceptible to good arguments. Apparently, we believe things for unexamined reasons, cherry-pick evidence to support our intuitive beliefs, and minimize the significance of inconvenient evidence.

These findings contribute to a general skepticism about people’s capacity for democracy, and I fear that this skepticism is self-reinforcing. If we presume that humans cannot reason well, why would we try to build institutions that promote reasoning? Only half jokingly, I sometimes say that the theme of current social science is: people are stupid and they hate each other.

But I also argue that at least some of this research employs methods that are biased against discovering rational thought. In particular, if you ask random samples of people disconnected survey questions that interest you (not them) and then use techniques such as factor analysis to find latent patterns, you will, indeed, often discover that people are stupid and hate each other. More prosaically, you will develop scales for latent variables like knowledge or tolerance that yield poor scores. But such methods may overlook the idiosyncratic ways that reasons influence individuals on the topics that matter to them.

Of all people, those who believe in false conspiracy theories are generally seen as the least susceptible to good reasons; and previous efforts to convince them have often failed. However, in a 2024 Science article, Thomas H. Costello, Gordon Pennycook, David G. Rand report results of an intervention that substantially reduced people’s commitment to conspiracy theories, not only in the short term, but also two months later.

In this study, holders of conspiracy theories wrote about why they held their beliefs, and then an AI bot held a conversation with them in which it supplied reliable information directly relevant to the specific factual premises of each respondent. For instance, if a person believed that 9/11 was an “inside job” because Building 7 collapsed even though no plane hit it (see Wood and Douglas 2013), the AI might provide engineering information about Building 7. Many people were persuaded.

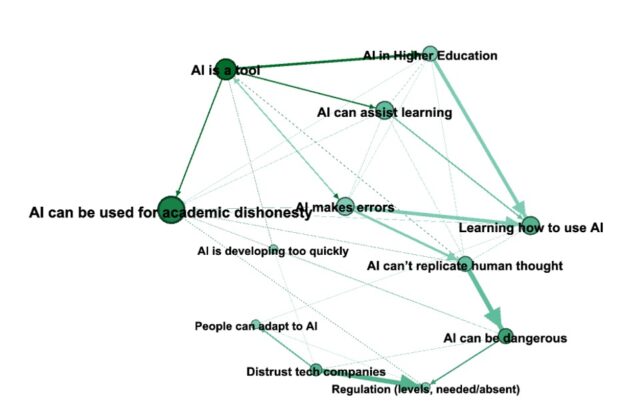

These results are consistent with a study of conversations with canvassers who succeeded in persuading many voters “by listening for individual voters’ … moral values and then tailoring their appeals to those moral values” (Kalla, Levine, A. S., & Broockman 2022). The two studies differ in that one used people and the other, an AI bot; and one emphasized facts while the other focused on values. But both results point to a model in which each person holds various beliefs that are more-or-less connected to other beliefs as reasons, forming a network. Beliefs may be normative or empirical–they function very similarly. Discourse involves stating one’s beliefs and their connections to other beliefs that serve as premises or implications.

People actually do a lot of this and are relatively good at assessing the rigor of such conversations when they observe them (Mercier and Sperber 2017). However, many of our methods are biased against discovering such reasoning (Levine 2024a and Levine 2024b), leaving us with the mistaken impression that we are a bunch of idiots incapable of self-governance.

Sources: Costello, T. H., Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2024). Durably reducing conspiracy beliefs through dialogues with AI. Science, 385(6714); Wood MJ, Douglas KM. “What about building 7?” A social psychological study of online discussion of 9/11 conspiracy theories. Front Psychol. 2013 Jul 8;4:409; Kalla, J. L., Levine, A. S., & Broockman, D. E. (2022). Personalizing moral reframing in interpersonal conversation: A field experiment. The Journal of Politics, 84(2), 1239-1243; Mercier, H. & Sperber D, The Enigma of Reason (Harvard University Press 2017; Levine, P. (2024a). People are not Points in Space: Network Models of Beliefs and Discussions. Critical Review, 1–27 (2024a), and Levine, P. (2024v). Mapping ideologies as networks of ideas. Journal of Political Ideologies, 29(3), 464-491.