- Facebook192

- Threads

- Bluesky

- Total 192

Almost every day, I am in conversations about protests on US college campuses. Some of these encounters take place at Tufts (in committees or one-on-one with students and colleagues), but I have also been part of discussions at Stanford, Harvard, and Providence College, and in DC–just to mention events during April.

In decades past, I would have posted frequent reflections here. These days, I am relatively quiet. I hear the argument that people in positions like mine should speak out more. I think I disagree, for four reasons.

First, although taking positions can be appropriate, or even obligatory, it can create challenges if one wants to facilitate open discussions in settings like classrooms or if one wants to advise and help people who have divergent views. I am privileged to receive requests for advice from people with almost the full range of positions on Israel/Palestine, and my interpretation of my own professional role is that I ought to try to help them all.

Second, I often find myself wrestling with what individuals have said in various settings. Sometimes I am moved, challenged, and educated, and sometimes I am somewhat appalled. However, these tend to be confidential statements that are not suitable for public assessment.

Third, although I believe that everyone has a right to form and express opinions, there is also value in talking when you have a solid basis for your views and listening when you don’t. Restraint is especially important for people in my kind of position (as a full professor and associate dean)–people whose opinions may have more weight than they deserve. Just because I teach Civic Studies does not mean that anyone needs to listen to me about Israel/Palestine.

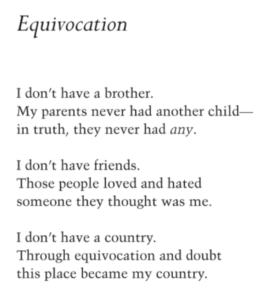

Fourth, there are other people who should be heard: those whose views are well-informed, complex, and challenging in various ways. I feel an obligation to find and share those voices but not to compete with them. (Just as one example: “Najwan Darwish on living in doubt.”)

For whatever it may be worth, my views on Israel/Palestine would probably align best with “What being pro-Palestine means to me / my platform” by Ahmed Fouad Alkhatib. He is sharply critical of both Hamas and the Israeli government. My views on campus speech and civil disobedience are libertarian, with a strong tilt toward countering speech with speech instead of banning or punishing it. (And yes, that does also apply to really nasty speech.) In thinking about movement tactics and strategy, I’d go back to Bayard Rustin’s “From Protest to Politics” (1965). I’d interpret nonviolence not as a set of restrictions (i.e., don’t cause physical harm) but as a powerful repertoire of strategies that can accomplish political goals while increasing the odds that the activists themselves will be wise. (Please join this summer’s Frontiers of Democracy conference for more discussion of that topic.) Finally, I would support efforts to promote dialogue and listening across differences, but not to the exclusion of adversarial rhetoric, which is also essential in a democracy.

The previous paragraph was something of a disclosure, and I will regret making it if it discourages people who disagree with any of it from engaging with me.