- Facebook13

- LinkedIn1

- Threads1

- Bluesky1

- Total 16

Political science is a heterogeneous discipline, and the various subfields are prone to interpret the Trump Administration and MAGA very differently.

- Comparativists compare and contrast political systems around the world. This approach could yield various interpretations of MAGA, but an influential interpretation assigns Trump to the category of modern authoritarianism, which is on the rise (Levitsky & Ziblatt, 2018). We learn that personalist, populist authoritarians in many countries have a toolkit that works for them. They don’t cancel elections or ban parties but manipulate the system from the executive branch, subject their critics to costly investigations, apply pressure to media conglomerates to influence journalism, etc. Not every current authoritarian has succeeded–consider South Korea and Brazil. But many have prevailed, and therefore comparativists tend to be alarmed about the situation in the USA.

- Scholars of American political development think about this country historically, often looking not only at our government and politicians but also at culture and social movements (Smith & King 2024). They are likely to notice precedents and echoes from American history and observe that prominent current debates are about how to interpret the past. Trump may remind them less of Hungary’s Victor Orban than of segregationist politicians. They may focus less on Trump as an individual actor and more on persistent strands of nativism and white nationalism in the USA.

- Political theorists are intellectually diverse, but most of us spend at least some of our time reading works from a wide variety of eras and perspectives that pose fundamental questions about government and politics. A disproportionate number of these classic works discuss revolutionary change, and some of them advocate it. Consider Plato and Aristotle, Hobbes and Rousseau, or Marx and the Nazi theorist Carl Schmitt, as examples. Even philosophers who oppose revolution are often primarily concerned about it. Therefore, political theorists are quick to imagine that our regime may be on the verge of breaking down. And we are prone to assign MAGA an ideological label, whether we name it populist, nationalist, neo-fascist, neoliberal, or something else.

- Scholars of social movements may ask whether MAGA is a bottom-up movement, but mainly they study anti-Trump movements, asking whether they will prevail and what may increase their odds of success. For example, Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan (2011) noticed that every nonviolent social movements that has mobilized at least 3.5% of its nation’s population has succeeded in modern times. Chenoweth recently discussed the “3.5% rule” with Paul Krugman, giving a nuanced answer to the question whether an anti-Trump movement will defeat the current administration if it can activate 3.5% of the US population. Note that in this framework, the main path of social change is not via elections but on the streets.

- Scholars of American government and political behavior use empirical tools of social science (analysis of voting records, surveys, and interviews or focus groups) to identify trends and patterns in US politics. They are likely to view Donald Trump as a lame-duck second-term president with approval ratings in the low 40s (and falling just lately). They see regular patterns playing out, such as the tendency for the electorate to move in the opposite ideological direction from the incumbent president. Most trends suggest that Democrats will win in 2026 and probably 2028. This framework predicts that Republicans will become burdened by an unpopular, term-limited Republican president and will begin to distance themselves from him. More basically, it assumes that elections will unfold as normal, that we will have two parties, that both will compete for the median voter, that the main vehicle for public opposition is an election, etc.

In my own writing and extracurricular work, I have been trying to support social movements against authoritarianism. Lately, I have been offering trainings–most recently at the excellent Dayton (OH) Democracy Summit — on how to resist authoritarianism from the bottom up. Here is a video of my standard talk.

Thus, I am applying the comparativists’ framework plus social movement scholarship. However, I am not completely committed to this combination. It is plausible that scholars of American government are right, and the usual patterns of US politics will reassert themselves. I am using a precautionary principle: taking preventive action in case of a disastrous outcome.

Predicting the next three years is difficult because we don’t know two crucial variables.

One variable is the performance of the economy in the next months. So far, it is holding up pretty well considering all the stress. The main indicators are not really very different from last year. Voters are unhappy but not facing an economic meltdown.

The economy could improve, boosting Donald Trump. (The Supreme Court may help by striking down the tariffs). The economy could keep puttering along. Or it could tip into a significant recession. If that happens, scholars of American political behavior would predict a realignment in favor of Democrats, and comparativists might expect Trump to attempt drastic action to save himself.

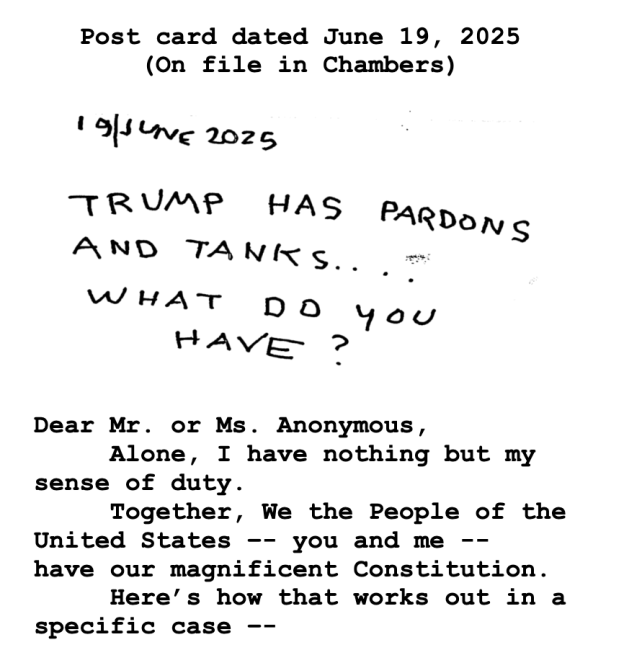

The other unknown variable is the behavior of Trump and his inner circle. They have crossed many bright lines: choosing political opponents for investigations, pardoning rioters, deploying troops in selected cities, and shuttering whole departments that are authorized and funded by statute. But they could do a lot more, such as invoking the Insurrection Act, deploying ICE against peaceful protesters, or suspending elections.

Comparativists tell us that subtler methods of authoritarian control work better in the 21st century. Using drastic methods would indicate weakness. Nevertheless, heightened drama could end with victory or defeat for Trump. The regime might succeed in suppressing opposition, or it might provoke a much larger popular response that succeeds. A common pattern is: protest –> state violence –> protests that mourn and celebrate the victims –> state violence against the mourners –> larger protests –> victory for the grassroots movement.

Finally, Trump has some personal characteristics that make him hard to classify. One is that he seems to care almost entirely about his own welfare. All other modern American presidents have wanted to enact legislation. That is the main way to change society durably. A president can only sign a bill after both houses of Congress have passed it. Therefore, all modern presidents have cared deeply who prevails in Congress.

But Trump does not seem to care about legislation. He signed nothing significant during his first term except budgetary changes. The Republicans loaded a lot of provisions into the “Big Beautiful Bill” that Trump signed on July 4, but even most of those were budgetary.

Meanwhile, Trump has radically–but perhaps not durably–changed government through unilateral executive action. Looking forward, he may not care very much whether Democrats win in 2026. He can ignore subpoenas, avoid removal by holding at least 34 votes in the Senate, and continue to govern unilaterally from the White House.

On one hand, this means that he is less likely to take drastic steps to prevent an electoral defeat in 2026. I think he has always expected to face a Democratic Congress in 2027 and 2028. He won’t pass any laws, and he may have difficulty appointing judges, but that won’t matter much to him. On the other hand, it means that no one in Congress–including congressional Republicans–will have much leverage over him. We may not see the usual pattern of the president’s party trying to constrain him to save themselves.

I think that Trump and many around him are incurring legal liability. Increasingly, as his term ends, we may see them primarily concerned about avoiding prosecution in 2029 and thereafter. Similar concerns could begin to influence private organizations that could be charged with bribery for assisting Trump. This phenomenon is common around the world–hence very familiar to comparativists. It raises questions about whether Trump will try to suppress elections just to avoid legal repercussions (although he could use preemptive pardons instead), and whether it will be necessary to negotiate an amnesty of some kind.

See also Trump: personalist leader or representative of a right-wing movement?; Trump, Modi, Erdogan; why political science dismissed Trump and political theory predicted him, revisited. Sources: Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, How Democracies Die (Crown 2018); Smith, Rogers M., and Desmond King. America’s new racial battle lines: Protect versus repair. University of Chicago Press, 2024 Chenoweth, Erica, and Maria J. Stephan. Why civil resistance works: The strategic logic of nonviolent conflict. Columbia University Press, 2011.