- Facebook31

- Threads

- Bluesky

- Total 31

I’m about to conduct a study in partnership with a civic association in the midwestern United States. It should yield insights that can inform this association’s plans and help me to develop a method and related theory. I have IRB approval to proceed, using instruments that are designed.

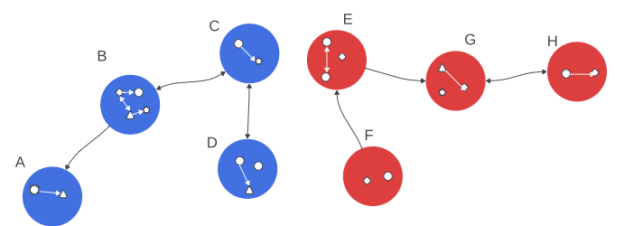

In the meantime, a colleague alerted me to an impressive new paper by Dalege, Galesic and Olsson (2023) that uses a very similar model. Fig. 1 in their paper resembles the image I’ve created with this post. These authors make an analogy to physics that allows them to write about spin, energy and temperature. I don’t have the necessary background to replicate their analysis but will contribute relevant empirical data from a real-world group and some additional interpretive concepts.

We will ask members of the association to what extent they agree with a list of relevant beliefs (derived from their own suggestions in an open-ended survey). We will ask them whether each belief that the individual endorses is a reason for their other beliefs. As a hypothetical example, you might think that the organization’s youth programming is important because you believe in investing in young people. That reflects a link between your two beliefs. We will also ask members to name their fellow members who most influence them.

In the hypothetical image with this post, the circles represent people: members of the group. A link between any two members indicates that one or both have identified the other as an influence. That is a social network graph.

The small shapes (stars, circles, etc.) represent the beliefs that individuals most strongly endorse. The arrows between pairs of beliefs indicate that one belief is a reason for another. This is a belief-network.

Reciprocal links are possible in both the social network and the belief networks.

Before analyzing the network data, I will also be able to derive some statistics that are not directly observed. For example, each node in both the social network and the belief networks has a certain amount of centrality, which can be measured in various standard ways. I can also run factor analysis on the responses about beliefs to see whether they reflect larger “constructs.” (Again, as a hypothetical example, it might turn out that several specific responses are consistent with an underlying concern for youth, and that construct could be measured for each member.)

I plan to test several hypotheses about this organization. These hypotheses are not meant to be generalizations. On the contrary, I expect that for any given organization, most of the hypotheses will turn out to be false. The purpose of testing them is to provide a description of the specific group that is useful for diagnosis and planning. Over time, it may also be possible to see which of these phenomena are most common under various circumstances.

Hypotheses to test

H1: The group is unified

H1a: The group is socially unified to the extent that its members belong to one network connected by interpersonal influences. The denser the ties within the connected network, the more the group displays social unity.

H1b: The group is epistemically epistemically unified to the extent that members endorse the same beliefs, and to the extent that these shared beliefs are central in their belief networks.

H2: The group is polarized.

H2a: The group is socially polarized if many members belong to two separate subgroups that are connected by interpersonal influences but are not connected to each other, as depicted by the red and blue clusters in my hypothetical image.

H2b: The group is epistemically polarized if many members endorse belief A, and many other members endorse B, but very few or no members endorse both A and B. If A and/or B also have high network centrality for the people who endorse them, that makes the epistemic polarization more serious. (Instead of examining specific beliefs, I could also look at constructs derived from factor analysis.)

H3: The group is fragmented

H3a: The group is socially fragmented if many members are connected by influence-links to zero or just one other member.

H3b: The group is epistemically fragmented if no specific beliefs are widely shared by the members.

H4: The group is homophilous if individuals who are connected by influence-ties are more likely to endorse the same beliefs, or have the same central beliefs, or reflect the same constructs, compared to those who are not connected. If the opposite is true–if socially connected people disagree more than the whole group does–then the group is heterophilous.

H5: There is a core and a periphery

H5a: There is a social core if some members are linked in a relatively large social network, while most other members are socially fragmented.

H5b: There is an epistemic core if many (but not all) members endorse a given belief, or a given belief is central for them, or they share the same constructs, while the rest of the organization does not endorse that belief.

H6: Certain members are bridges

H6a: A person is a social bridge if the whole group would be socially polarized without that person.

H6b: A person is an epistemic bridge if the whole group would be epistemically polarized without that person.

H7: Members tend to hold organized views: This is true if the mean density of individuals’ belief networks (the mean number of links/nodes) is high, indicating that people see a lot of logical connections among the things they believe.

Our survey respondents will answer demographic questions, so we will be able to tell whether polarized subgroups or core groups have similar demographic characteristics. Hypothetically, for example, a group could polarize epistemically or socially along gender lines. And we will ask general evaluative questions, such as whether an individual feels valued in the association, which will allow us to see whether phenomena like social- connectedness or agreement with others are related to satisfaction.

What to do with these results?

Although the practical implications of these results would depend on the organization’s goals and mission, I would generally expect polarization, fragmentation, the existence of cores, and homophily to be problematic. These variables may also intersect, so that an organizations that is socially polarized, epistemically polarized, homophilous, and reflects highly organized views is especially at risk of conflict. A group that is fragmented and reflects disorganized belief-networks at the individual level may face a different kind of risk, which I would informally label “entropy.”

Being unified can be advantageous, unless it reflects group-think or social exclusivity that will prevent the organization from growing.

Once an organization knows its specific challenges, it can use appropriate programming to make progress. For instance, if the group is socially fragmented, maybe it needs more social opportunities. If it is polarized, maybe a well-chosen discussion could help produce more bridges. If it displays entropy, maybe it needs a formal strategic plan.

I would generally anticipate that bridges are helpful and should be supported and encouraged. In our study, all the data will be anonymous, so our partner will not know the identity of any people who bridge gaps. But a different application of this method could reveal that information.

Although I am focused on this study now, I remain open to partnerships with other organizations so that I can continue this research agenda. Let me know if you lead an organization that would like to do a similar study a bit later on.

Reference: Dalege, J., Galesic, M., & Olsson, H. (2023, April 12). Networks of Beliefs: An Integrative Theory of Individual- and Social-Level Belief Dynamics. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/368jz. See also: Analyzing Political Opinions and Discussions as Networks of Ideas; Mapping Ideologies as Networks of Ideas; seeking a religious congregation for a research study