- Facebook336

- Total 336

In The Washington Post, Amy Gardner reads some tea leaves that might foretell youth turnout in November.

On one hand, the good news: “In Pennsylvania, youth voters have made up nearly 60 percent of all new registrants, TargetSmart reported in September. The share of the electorate that is under age 30 has grown since 2017 in several key states, including Nevada, North Carolina and Florida, according to state voter registration data tracked by the firm L2. In Virginia, requests for student absentee ballots, at about 30,000, are about 50 percent higher than in last year’s gubernatorial election.”

We could add that CIRCLE’s youth polling finds much higher levels of intent to vote than we have seen recently. And these data from Texas look promising:

On the other hand, Gardner notes,

On the other hand, Gardner notes,

There are plenty of reasons for skepticism about an age group that typically performs dismally at the polls. In 2016, young Americans were expected to turn out heavily against Trump, but the actual share of voters under 30 who cast ballots was 43 percent of eligible voters — about the same as the previous presidential election in 2012 and lower than 2008. (Overall turnout in 2016 was 60 percent.)

Midterm performance is typically far worse: Just 16 percent of young Americans cast ballots in 2014. The highest midterm turnout among voters under 30 in the past three decades was a mere 21 percent in 1994.

And some of the tea leaves seem to foretell just a modest improvement:

In Nevada, young voters’ share of the electorate was 18.6 percent in August, up from 17.5 percent in September 2017, according to L2. In North Carolina, it was 18.3 percent in October, up from 16.7 percent in September 2017. And in Florida, it was 16.6 percent in September, up from 15.6 percent a year earlier.

Meanwhile, in Politico, Marc Caputo, Matt Dixon, and Isabel Dobrin write:

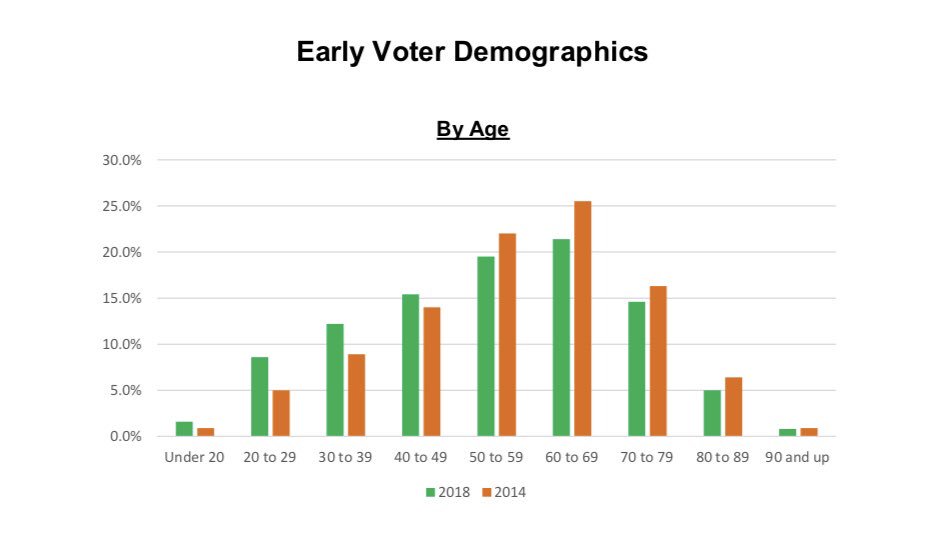

THE YOUNG PEOPLE WILL … STAY HOME? — Remember all that talk of how “the young people will win” and come out in force in Florida, especially after the Parkland massacre? So far, it’s not happening. Voters between the ages of 18-29 are 17 percent of the registered voters in Florida but have only cast 5 percent of the ballots so far. They tend to vote more Democratic. Meanwhile, voters 65 and older are 18.4 percent of the electorate but have cast 51.4 percent of the ballots. And older voters tend to vote more Republican.

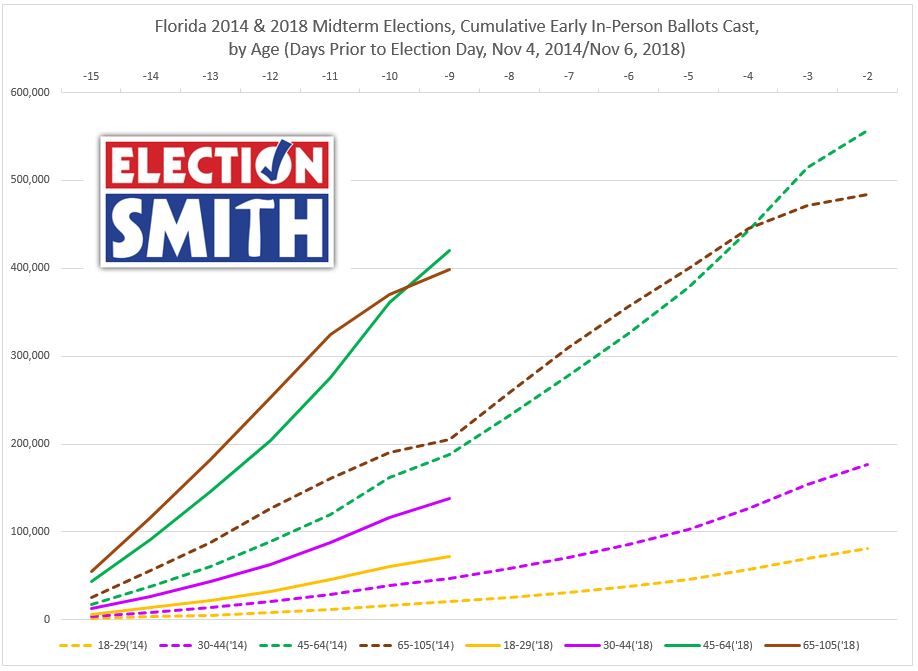

Their analysis is based on Daniel Smith’s chart of the early votes so far in Florida, which shows all age groups rising but youth by the smallest amount:

A bunch of different statistics are being cited here: the number of voters or registrants in various age groups, the turnout (the percentage of eligible people in each category who actually voted), and the share of the electorate (what proportion of all voters fit in each category). These articles also cite statistics about registration, early voting, and total voting. It’s easy to get confused.

I expect turnout to rise for the population as a whole, in large part because of the actual and perceived high stakes of the 2018 election. I think youth turnout will also rise but youth will face a challenge keeping pace with the general increase. The difference between them and older voters will probably look better than in Dan Smith’s chart, because early voting seems to appeal especially to older people.

But we could still see various scenarios.

If youth turnout and share of the electorate both rise, it will be a great year for youth voting. Youth turnout could actually fall, but that would really surprise me. If youth turnout rises but no faster than–or not as fast as–the turnout of older people, then youth share will shrink. This will be reported by many news outlets as a decline. That interpretation will not be an outright error. If you want to exercise more influence on the outcome, you must increase your share of the vote. A flat or shrinking share means having no more influence. Also, if turnout rises but youth turnout rises less than average, it will pose questions about the impact of the nonpartisan and partisan efforts specifically to engage youth.

But it will also be true that more youth have voted, which will be worth celebrating if you care about youth engagement. And it will break a pattern, because historically youth turnout has been remarkably flat in midterm elections. Breaking that pattern might be a small positive step even if youth share shrinks slightly.