- Facebook220

- Total 220

The New York Times has published an “Invitation to a Dialogue” by our friend Harry Boyte. Harry writes:

In response to the killings in Connecticut (“Looking for America,” column, Dec. 15), Gail Collins calls for breaking the silence about gun laws. But the discussion needs to address more than guns and extra bullet capacity.

The spreading pattern of violence grows from many sources, not simply guns. These include television news coverage, video games and movies, as well as family and community dynamics.

Public policy on guns can play a role. But mitigating the devaluation of human life will require a much more powerful civic response. Families, schools, colleges, congregations, businesses, consumer groups and others need to work together to challenge and change the culture of violence, reaching well beyond debates about the Second Amendment.

For instance, parents and teachers can develop early warning strategies; local journalists can spotlight programs that work for disaffected young adults; and young people themselves can organize peer-to-peer anti-bullying and anti-violence campaigns.

We need a broad citizen movement if we are to reweave the social fabric.

Readers are invited to respond today in order to for their comments to be considered for publication on Sunday. E-mail: letters@nytimes.com.

I’ll offer a few comments about what would make for a good discussion:

1) Everything should be on the table, certainly including gun control. That issue must not be suppressed because of the Second Amendment, the power of the gun lobby, or the fact that the President has been accused of wanting to take away people’s guns when actually he had no intention of addressing that issue. On the other hand, we shouldn’t ignore the very spotty empirical evidence for the benefits of the various gun control provisions that are being serious considered. Symbolic legislative victories do us no credit. For example, to reinstate the old federal assault weapon ban seems irrelevant, since Connecticut already had the same policy via state law, and the gun used in Newtown was legal.

2) We should define the problem broadly and with analytic clarity, not being driven by Newtown or any other notorious case alone. Huge numbers of young Americans are killed by guns every year. Policies and community actions that would reduce the overall homicide rate may be irrelevant to the still-rare cases of mass murder/suicide.

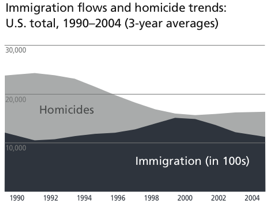

Online, you can find many comparisons of the numbers of children killed in Newtown and in Chicago this year. In Chicago, the 2012 toll is said to be 58, although I can’t confirm that from official statistics. In any case, 290 school-age children were shot in Chicago in 2009, and that is completely unacceptable. As I’ve written before, “If the fundamental responsibility of a government is protect citizens’ lives, then such violence puts the very legitimacy of the regime in question, to say nothing of the human tragedy that each gunshot represents.” But teen homicide rates have generally been falling, and although Chicago draws appropriate attention because of its recent spike, New York City has seen declining numbers of homicides for 20 years. A productive discussion would not assume the premise that violence is rapidly increasing, because that can lead to irrelevant solutions. By the way, plausible explanations for the general decrease in violent crime include lead-paint abatement and immigration:

3) As Harry argues, we should think about much more than governmental policies and the kinds of causes that governments can address. I suspect that two reasons for the rash of mass school shootings are the general glorification of violence and the obsessive media attention devoted to tragedies in schools. The government cannot regulate the news and entertainment media (in relevant ways), but we citizens can choose which media to consume and produce. Citizens’ movements have influenced prevailing attitudes towards race, gender, sexual orientation, disabilities, littering, and drunk-driving, among other matters. The glorification of violence in our culture–whether that is increasing or declining–is an example of a problem that we must address without much help from the state.

Meanwhile, pervasive community-level changes are being made without getting a lot of attention. Elementary schools now drill students on how to respond to violent attacks; schools’ security systems and policies are being redesigned. Are these changes wise? Are the best strategies being used? Do we talk about these threats in appropriate ways?

4) How to define the topic or set the frame of the discussion is a difficult question, as anyone knows who has organized deliberative events. Watch the president take a question on gun control and try to place that issue in the larger context of children’s welfare and safety. To be sure, he has political reasons to try to make that shift–he has done a lot for children’s health but little about gun violence. Nevertheless, he may be right that child welfare rather than school shootings or gun control is the best frame.