- Facebook198

- Twitter1

- Total 199

It is important for left and center-left political parties to rely on lower-income voters, who–nowadays–are also people with less educational attainment. Then the left’s political leadership will be accountable to disadvantaged people. Since they identify with the left, they will try to serve their core voters by promising more funds and more regulation. I generally favor such policies, but even if you do not, you should acknowledge that taxing, spending, and regulating are compatible with a constitutional democracy. If you want to oppose the left, you can vote for the right.

It is equally important for center-right parties to depend on people with higher incomes (which generally means more education), because then they will have incentives to advocate lower taxes and less regulation. I tend to oppose such policies, but I would acknowledge–and urge others on the left to accept–that trying to shrink the size of government is compatible with constitutional democracy. People who have reasons to shrink government need a political outlet. Again, the way to oppose their position is to vote for the other side. This debate is a good one.

As long as the parties split the electorate this way, they will have incentives to act reasonably on matters outside their core interests. A pro-business party rooted in the upper stratum of society can easily support civil liberties and a safety net. A left party dependent on working class voters will want to protect economic growth. Both should defend the basic constitutional order.

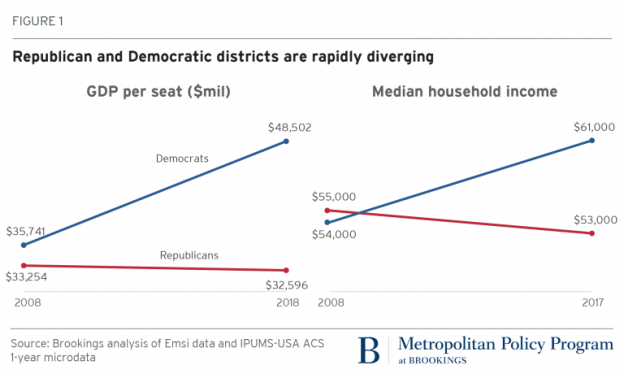

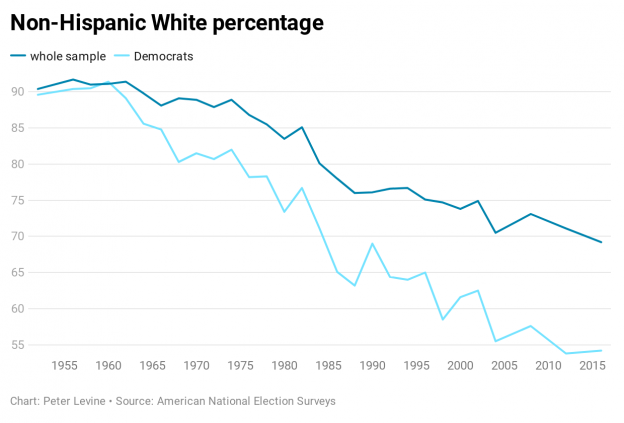

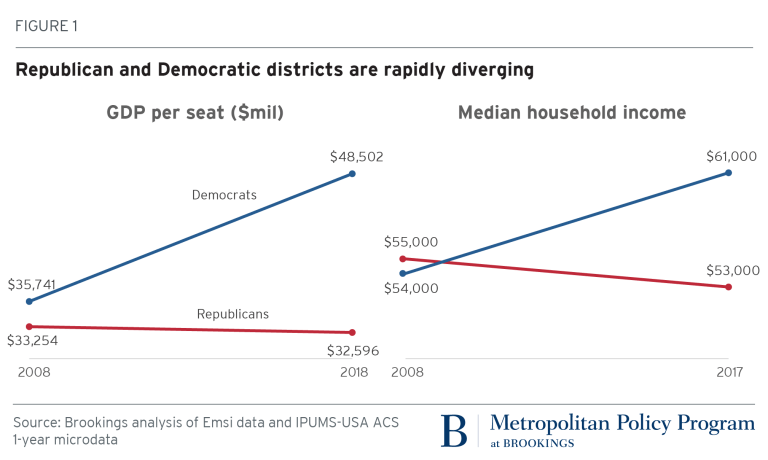

Unfortunately, this neat arrangement has been scrambled in many developed, democratic countries. Considerable numbers of highly educated people vote left, even forming the base of the center-left parties, while many working-class people have shifted to the right. Democrats now represent the 17 richest congressional districts and most of the richest 50. In the aggregate, Democratic districts are wealthier than Republican ones. (Race is certainly relevant in the USA, and I will say more about that later.)

This situation is dangerous because of the incentives it creates. A center-left party that relies on highly educated people will want to preserve the society’s most advantaged institutions: its most dynamic industries, thriving communities, and elite universities. Since it’s on the left, it won’t explicitly defend inequality, but it won’t really undermine it, either. It will prefer symbolic gestures of inclusion and equity that don’t shake the social foundations. Basically, advantaged individuals will assume that they can retain their own nice neighborhoods, good schools, and satisfying jobs while allowing some newcomers to join them. If such voters represent the main force on the left, social transformation becomes impossible.

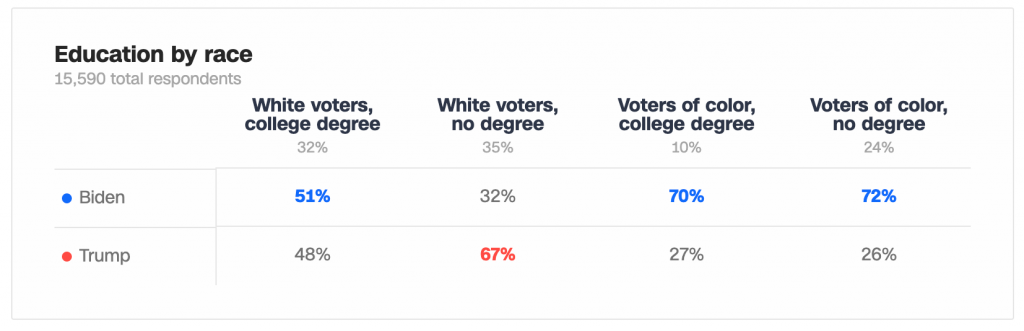

Nevertheless, the center-left party will offer the least-bad option for people of color, since diversity and inclusion are better than outright exclusion. Thus Biden drew 70% of voters of color along with a majority of college-educated white voters.

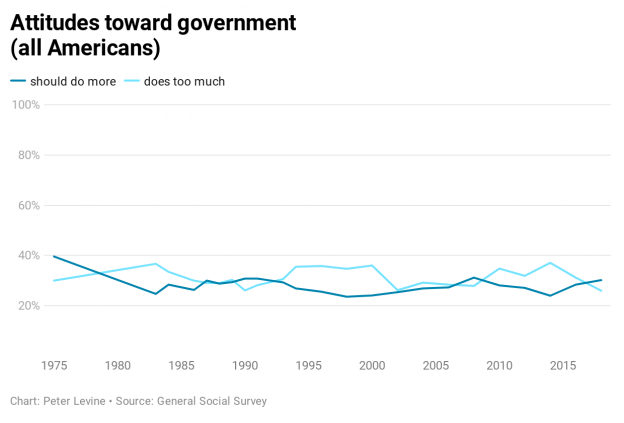

For their part, right parties that are based in working-class, low-income communities will have incentives to turn ethno-nationalist, xenophobic, and authoritarian. Being on the right, they cannot embrace social democracy. They could offer libertarian alternatives: getting the state off people’s backs. Unlike authoritarianism, libertarianism is compatible with constitutional democracy. However, surveys never show much support for truly libertarian policies–and less so today, after the neoliberal revolution has played out. Ethno-nationalism has much wider support.

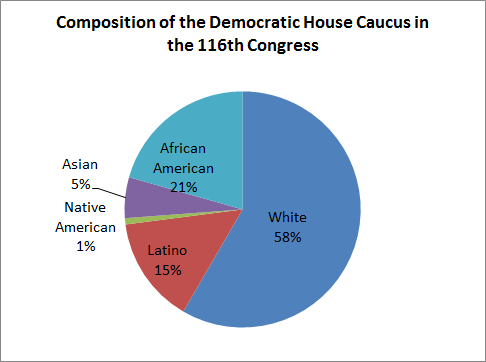

When the parties invert in this way, the left tends to become moderate–excessively so, in my view–but it also generates a critical flank. Right now, the Democrats’ critical flank is led by younger politicians of color who represent urban communities with many lower-income voters of color. They have incentives, as well as genuine commitments, that anchor them on the left. But they are outnumbered within their own party by politicians who represent and reflect high-income communities. If we had a multi-party system, these factions would split and then negotiate about whether to form a coalition in Congress. In our duopoly, the strife occurs within the party and is constrained by difficult calculations.

Meanwhile, the Republicans have strong and palpable incentives to move in a racist and authoritarian direction, jettisoning their libertarian impulses. Debate is less evident on their side of the aisle, since Trump supporters truly dominate the GOP’s elected ranks. Only a significant electoral defeat can re-empower the traditional conservatives, and that seems unlikely.

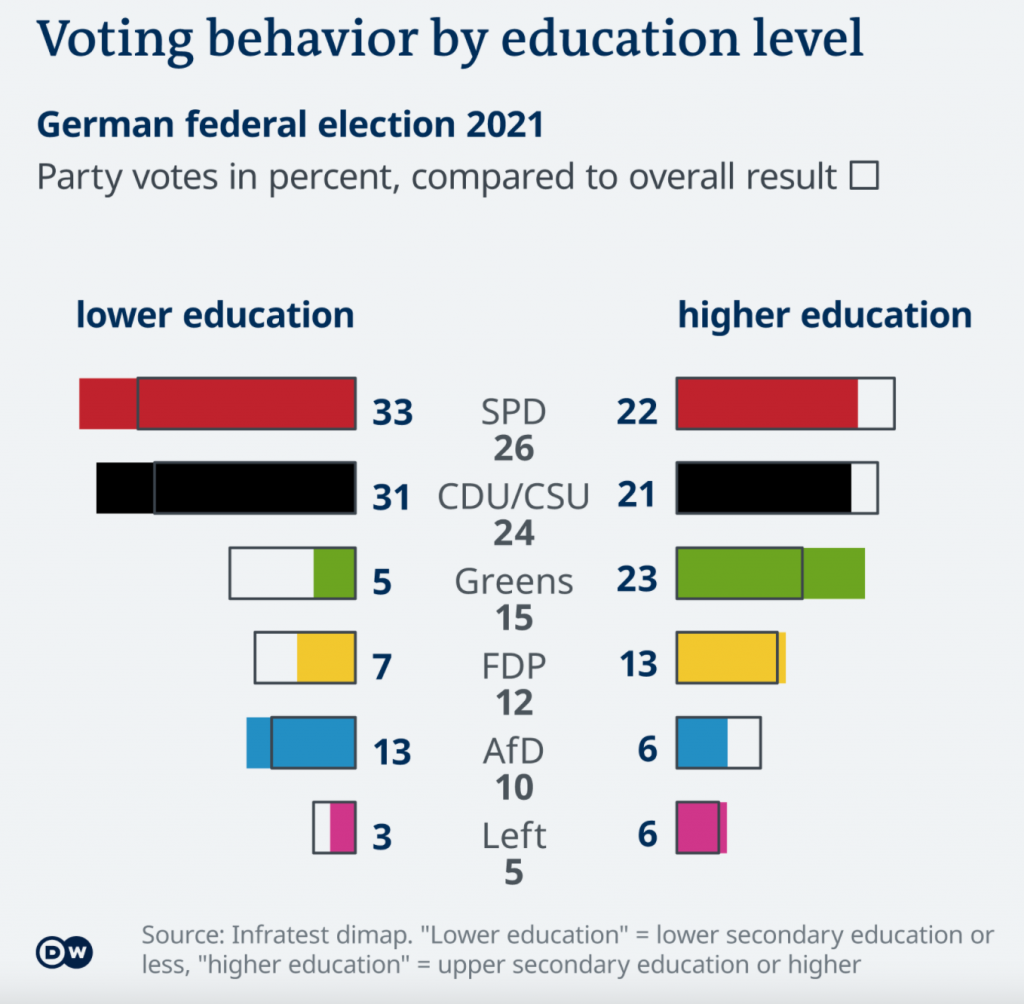

A similar inversion has been evident in several other countries, including Germany, where the Social Democrats (SPD) now attract highly educated knowledge-workers, while many blue-collar workers have moved right. (I graphed some historical trends here.) One election does not make a trend, but the results from the recent German election are somewhat encouraging. The SPD performed best among people with lower education: the working class. That is how a social-democratic party should perform. The Greens drew almost entirely from the top educational stratum. A red/green coalition would combine working class voters with the liberal intelligentsia, but with the working class in control because of their larger numbers. That coalition would resemble the Democrats if the Progressive Caucus were three times as big.

On the other hand, the hard right (AfD) is disproportionately working class, as is the center right (CDU). Although I do not expect the CDU and AfD to form a coalition in the near future, the temptation is real.

It will not be easy to get out of this situation. The Democrats could offer more tangible benefits to working class people of all races and ethnicities. One problem: policies that I would regard as beneficial are not always seen as such, for a variety of reasons. Besides, there is always a loose connection between policy and public opinion, given the genuine difficulty of discerning the effects of policies plus the low level of attention that most people give to public affairs.

To make matters even harder, Democrats are a loose group of entrepreneurial politicians who have their own constituencies–disproportionately wealthy ones. This means that Democratic leaders are not the best group to reach out to working-class voters, nor are their core supporters likely to support really bold policies. That is why I have been interested in tactics like investing in the Appalachian cities, whose mayors are Democrats.

See also: what does the European Green surge mean?; and why the white working class must organize