In the most recent New York Times national survey, Kamala Harris draws a majority (55%) of white voters with college degrees, and a larger majority (66%) of voters of color who have graduated from with college. She is ahead among non-college-educated people of color (61%), but 34 percentage points behind Trump among whites without college degrees.

Although race and class are both relevant, this survey and many others indicate that less education correlates with more support for conservative candidates in the USA and in many other countries.

I do not interpret this correlation to mean that schools and colleges change people’s political values, since evidence of such effects is limited. Rather, I see educational attainment as an indicator of social class, and I believe that class has reversed its postwar political significance in the USA and most of Europe. Current right-wing parties offer authoritarian and/or ethno-nationalist policies to working-class supporters, rather than libertarian policies for business owners. Meanwhile, center-left and even leftist parties have bourgeois supporters and so mostly offer symbolic policies. This combination threatens liberal democracy.

Several connected but distinct questions arise: What policies would promote a fair economy and society? What do working-class voters want? How can a party win an election if it begins with soft working-class support? And what combinations of policies, framings, and candidates appeal better to working-class voters?

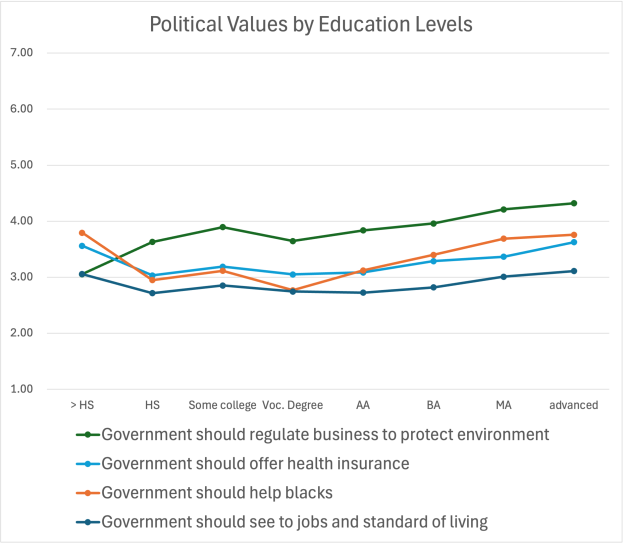

As a very small contribution to this discussion, I show two graphs derived from the 2020 American National Election Study–i.e., our most recent presidential election. They trace levels of agreement with four propositions that might serve as proxies for political ideology: should government provide medical insurance, regulate businesses to protect the environment, assist blacks (that’s how the ANES words its question), and guarantee jobs and a standard of living.

A mean response of 4 would suggest as much support as opposition for these ideas, so the graph above shows that all four tend to be unpopular. However, support generally rises with education levels. It appears that bourgeois voters are the most tolerant of activist government, which is problematic.

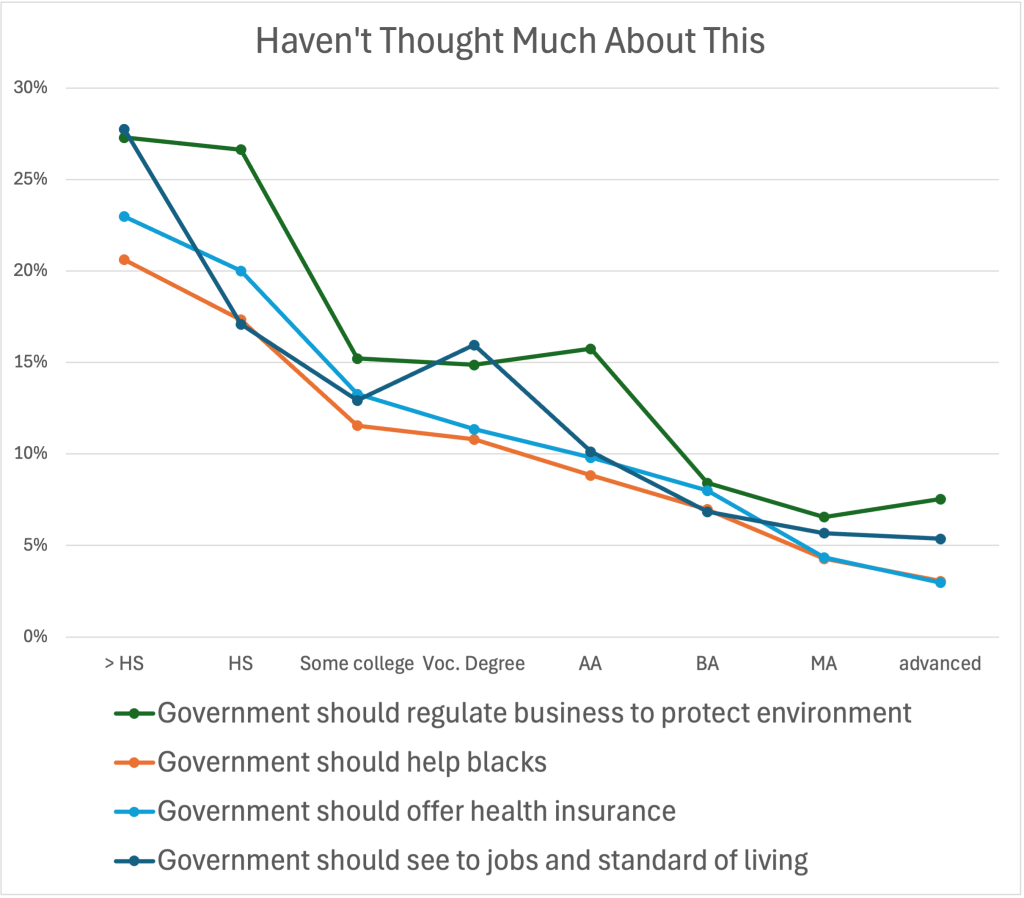

The second graph, however, displays the notably high rates of refusal to respond. The ANES allows people to say “I have not thought much about this” instead of answering each item. People with more education are much more likely to have thought about all four ideas.

Again, I am not sure this pattern is causal, i.e., that schools and colleges encourage students to think about these issues. For one thing, the data come from the whole US population; and for many of us, college was a long time ago. Rather, people in white-collar jobs and communities probably think and talk more about this kind of issue.

The second graph hints at a possible solution: without trying to sell anyone on any political ideology, we should encourage more people to think and talk about policy by supporting the forums and settings where working-class people exchange ideas and make sense of the social world, such as grassroots movements, unions, music and spoken word performances, and religious congregations that are relatively diverse politically.

See also: previous posts on the social class inversion in elections; a way forward for high culture