- Facebook170

- Total 170

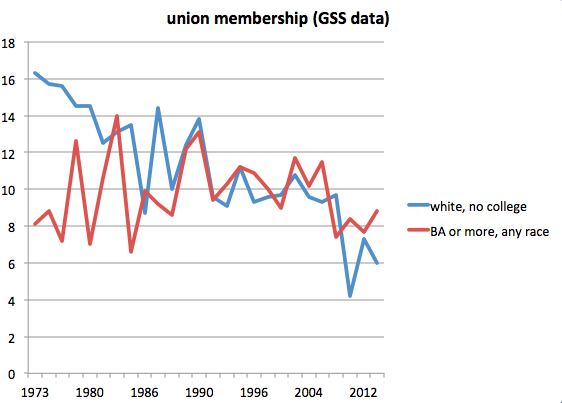

I’m back from a great meeting in Chicago in which one theme was the need to have honest, productive conversations between people who might support Donald Trump and members or supporters of movements like Black Lives Matter. I’d note a major obstacle: the fact that working-class white people–the demographic core of Trump’s support–don’t have organizations that answer to them. As an illustration, consider that just 6 percent of adult Whites without college educations now belong to unions. That’s below the rate for college graduates, many of whom have other organizations behind them.

A lack of organization blocks or distorts difficult discussions, for these reasons:

- It’s literally hard to convene people who aren’t organized. Absent organizations, conversations tend to be online or draw highly atypical individuals who show up of their own accord.

- People who have no organizations behind them usually feel powerless. If that’s how they feel, they are unlikely to want to participate in difficult conversations. Especially when the topic is their own ostensible privilege, they are likely to resist talking. To be clear: I believe that everyone who is White in the US gains privilege from that. But if I felt politically powerless, I would not be in a mood to have that conversation, especially with people who were better organized than I was.

- People without organizations end up being represented by famous individuals–celebrities–who claim to speak for them and who claim mandates on the basis of their popularity. Celebrities have no incentives to address social problems; they gain their fame from their purely critical stance. And they owe no actual accountability to their fans, since no one (not even a passionate fan) expects a celebrity to deliver anything concrete. Donald Trump is unusual in that he has moved from a literal celebrity to a presidential nominee; but he still acts like a celebrity, and presumably he will return to being a pure mouthpiece once the election is over. Meanwhile, back at the grassroots level, a person who feels represented by celebrities is unlikely to talk productively with fellow citizens who disagree.

- People without organizations cannot negotiate. For instance, imagine that an individual Trump voter becomes convinced of the case for reparations, or at for least for race-conscious policies aimed at equity. That person cannot literally support such remedies, because he has no means to enact them. All he can do is assent to their theoretical merit. That also means that he can’t get anything tangible out of a deal. He’s just being asked to concede a point.

In 1959, A. Philip Randolph helped found and led the Negro American Labor Council as a voice for civil rights within the labor movement. As he pressed and negotiated with his fellow labor leaders on matters of civil rights, he was giving their millions of White rank-and-file members the opportunity to discuss segregation and racism productively. Crucially, not only were the Sleeping Car Porters organized; so were the predominantly White autoworkers, steelworkers, and mineworkers. Randolph also had–and used–substantial leverage over a Democratic Party that was still dependent on working-class voters, White and Black.

I’m certainly not implying that everything went smoothly in those days and reached satisfactory conclusions, but Randolph at least had a strategy that made sense. In an era of niche celebrities, candidate- and donor-driven political parties, and weak civic institutions, that strategy looks much harder.

Counterargument: The Fraternal Order of Police is an organization. Its members, although diverse demographically and ideologically, need to be at the table for any discussion of racial justice. But the FOP has endorsed Trump; and in many local contexts, its spokespeople seem particularly unwilling to deliberate and negotiate. Hence being organized is not a path to productive conversations. … To which I’d respond: Privilege yields to political power. Only effective political action will bring a group like this to the table. But the police can come to the table because they are organized, and that creates a strategic opening that is absent when people with similar views aren’t organized. It also enables pressure to come from within. For instance, the association that represents 2,500 Black police officers in Philadelphia has called Trump an “outrageous bigot” even as the Philly FoP has endorsed him.

See also: why the white working class must organize.