- Facebook174

- Total 174

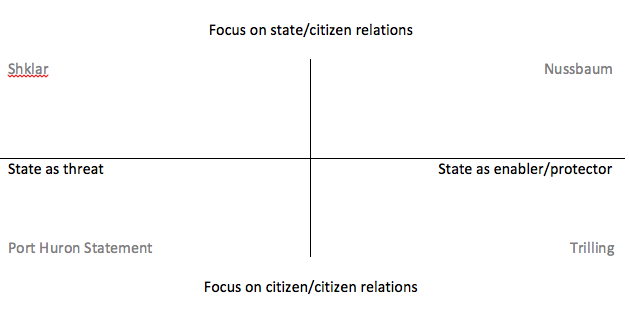

This simple typology might be helpful for distinguishing tendencies within liberal political thought. The x-axis measures attitudes toward the state, ranging from fear to enthusiasm. The y-axis measures the degree to which the state is central to politics. If you are primarily concerned with the state, you belong at the top, and if you focus on horizontal relations among people, you’re at the bottom.

Judith Shklar exemplifies the top-left quadrant. She is explicit that the question for liberals is how the state treats citizens, and the driving concern is the state’s potential for cruelty and oppression:

Given the inevitability of that inequality of military, police, and persuasive power which is called government, there is evidently always much to be afraid of. And one may, thus, be less inclined to celebrate the blessings of liberty than to consider the dangers of tyranny and war that threaten it. For this liberalism the basic units of political life are not discursive and reflecting persons, nor friends and enemies, nor patriotic soldier-citizens, nor energetic litigants, but the weak and the powerful. And the freedom it wishes to secure is freedom from the abuse of power and intimidation of the defenseless that this difference invites.[1]

Martha Nussbaum exemplifies the top-right. She is also fundamentally concerned with the government, but she emphasizes its potential to enhance human capabilities:

In the end it is government, meaning the society’s basic political structure, that bears the ultimate responsibilities for securing capabilities. [Government] must actively support people’s capabilities, not just fail to set up obstacles. … Fundamental rights are only words unless and until they are made real by government action.[2]

Despite the manifest disagreements between these two authors, both view politics mainly as a set of relationships between the state and citizens.

Down at the bottom right is someone like Lionel Trilling, who thinks that liberalism is about relations among citizens—“discursive and reflecting persons,” in Shklar’s phrase. In a liberal culture, fellow members of a community develop close, responsive relations with one another so that they can enrich their inner lives and develop mutual understanding before they seek to influence the state, their culture, or their community. In passing in The Liberal Imagination, Trilling endorses laws and institutions that enhance freedom and happiness (that puts him on the right side of the spectrum), yet he wishes to “recall liberalism to its first essential imagination of variousness and possibility, which implies the awareness of complexity and difficulty.”[3] For Trilling, sensitive literary criticism is a characteristic liberal act because it involves the recovery of another individual’s thought.

The bottom-left belongs to people who see great importance and positive potential in human beings when they relate appropriately to each other, and who fear the state as a threat to authenticity and creativity. This is at least a thread in the Port Huron Statement, which inaugurated the New Left in America:

Men have unrealized potential for self-cultivation, self-direction, self-understanding, and creativity. It is this potential that we regard as crucial and to which we appeal, not to the human potentiality for violence, unreason, and submission to authority. … Human relationships should involve fraternity and honesty. Human interdependence is contemporary fact; human brotherhood must be willed however, as a condition of future survival and as the most appropriate form of social relations. Personal links between man and man are needed, especially to go beyond the partial and fragmentary bonds of function that bind men only as worker to worker, employer to employee, teacher to student, American to Russian. … Loneliness, estrangement, isolation describe the vast distance between man and man today. These dominant tendencies cannot be overcome by better personnel management, nor by improved gadgets, but only when a love of man overcomes the idolatrous worship of things by man.

[1] Cf. Judith Shklar, The Liberalism of Fear, reprinted in Nancy L. Rosenblum (ed.), Liberalism and the Moral Life (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989), p. 27.

[2] Martha Nussbaum, Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach, pp. 64-5.

[3] Trilling, The Liberal Imagination: Essays on Literature and Society (New York: New York Review of Books, 2008), Preface (1949), p. xxi