- Facebook34

- Total 34

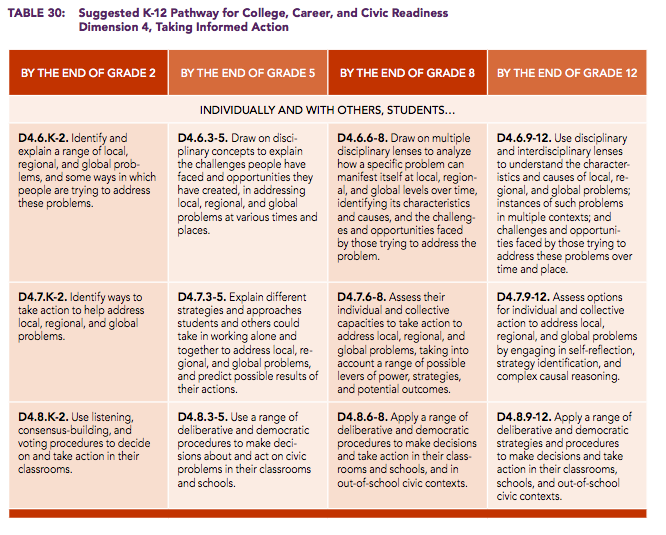

I am in St. Louis for the big annual gathering of social studies teachers, the National Council for the Social Studies conference. Last fall, the NCSS released a new voluntary framework for state standards entitled College, Career, and Civic Life (C3). For full disclosure, I helped write it. One part that seems especially important to me is the section near the end about “taking informed action” (shown below). I will be discussing why this is important and what it means in classrooms.

At each level, we ask students to analyze a problem, then consider options for addressing the problem, and then make deliberative decisions about what they will do. The scope of action expands from the classroom in grades k-2 to beyond the school by 12th grade.

These standards were written by a large group, but they are consistent with my personal view that good citizens deliberate. By talking and listening to people who are different from ourselves, we learn and enlarge our understanding. We check our values, strategies, and facts with other people. We form ideas about topics that we didn’t even consider before we talked and listened. We also make ourselves accountable to our fellow citizens.

But (I argue) deliberation is not enough. Talking without ever acting is pretty empty. You can say most anything without learning from the results or affecting the world. Deliberation is most valuable when it is connected to work or action. At least sometimes, we should be part of groups that talk about what we should do, then actually do what we have talked about doing, and then reflect on the experience, holding themselves ourselves for the results. This is both the best way to improve the world and the best way to learn to be a good citizen.

Concretely, “taking action” can mean many things: not just community service, and definitely not just political activism (which is hard for a public school to recognize), but also managing and leading student groups, organizing public events, and creating and sharing knowledge.

As Meira Levinson and I argue in the new issue of the NCSS journal, taking action is nothing new.* There is a great old tradition of American students being asked to deliberate and then act as part of their social studies classes. If anything, I suspect the prevalence of action has declined because high schools now mimic colleges (which makes social studies into History or Poli Sci 101 for teenagers) and because conventional standardized tests cannot measure students’ facility at deliberation and action. The new framework, if taken seriously, would require a whole new approach to assessing students’ work.

*Meira Levinson and Peter Levine, “Taking Informed Action to Engage Students in Civic Life,” Social Education, vol. 77, no. 6 (Nov/Dec, 2013) pp. 337-9