- Facebook18

- Total 18

Consider that:

- The same US government that can apparently tap almost any telephone in the world cannot harvest information that people voluntarily provide on the government’s own website regarding their eligibility for insurance.

- A private firm, CGI Federal, botches healthcare.gov. A private firm, Dell, employs the analyst, Edward Snowden, who leaks the NSA’s secrets.

- Snowden reveals (inter alia) that the NSA has been spying on Angela Merkel, whose main impact has been holding down government spending and debt throughout Europe, in keeping with neoliberal economic doctrine.

- Companies like Google and Facebook possess unprecedented knowledge of the private behavior and beliefs of citizens. They profess “outrage” at the government’s collection of private information. They call it “outright theft.” Apart from their annoyance at losing their data to the state, they fear that consumers will now be reluctant to share information on US-based networks–information that is currently worth about $1,200/person to firms like Google and Facebook.

- The Tea Party is a loose movement that professes support for free markets and resistance to government. Its power has presumably kept corporate taxes and regulations lower than they would be otherwise. Yet the US Chamber of Commerce and individual companies like AT&T and Caterpillar are so angry about the recent federal shutdown that they are spending significant money to defeat Tea Party-backed candidates in Republican primaries.

- Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg creates FWD.us to promote immigration reform. Through a subsidiary called Americans for a Conservative Direction, FWD.us funds conservative candidates who support reducing certain barriers to immigration. Through a different subsidiary called the Council for American Job Growth, it “reach[es] out to progressive and independent voters.”

One way to put these scattered points together is to talk about “the neoliberal state.” Big businesses basically get the policies they want, whether in the US, Germany, Russia, or in (nominally communist) China. Far from constraining them, the state is their assistant. The news consists of little skirmishes between particular businesses and forces not completely under their control: Tea Partiers, the national security apparatus, the US Attorney in Manhattan, and the Democratic Party. Business wins virtually all the skirmishes, and the underlying reality is even more favorable to its interests than the scattered conflicts suggest.

I mention the idea of the neoliberal state because I see that it contains a lot of truth. But I dissent in part on theoretical, moral, and strategic grounds:

Theoretically: we have to remember the problem of collective action. Each business gains from laissez-faire policies–but only a bit, and the competition gains as well. It is not in each firm’s self-interest to be too politically active. Eruptions like the Chamber versus the Tea Party, the Koch Brothers versus Obama, or Google versus the NSA show that it is genuinely difficult for a whole array of competing businesses to coordinate their efforts to achieve the ends they want. Clearly, ordinary people face even more daunting collective-action problems, but that is what political organizing is for.

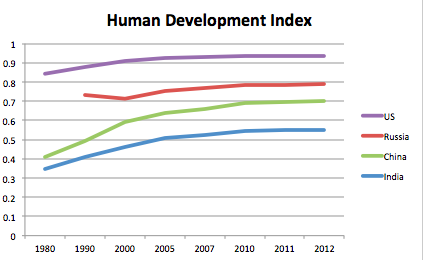

Morally: the critique of the neoliberal state ignores the benefits of global markets. The Human Development Index is a pretty good measure of actual well-being, incorporating not just per capita wealth, but also outcomes like health, education, safety, and women’s empowerment. This graph shows the trends in HDI since China and India opened their economies to direct foreign investment and became sensitive to global markets. The upward trends represent substantial net improvements in the lives of billions of human beings.

Strategically: the theory of the neoliberal state gives the impression that ordinary people have no power. That impression is itself disempowering. Elections in the US are influenced by cash, but no one literally has more than one vote. If we choose not to do what big businesses tell us to do, we win. A defeatist theory makes that less likely.

I am not saying that the governments of the US, the EU’s members, China, India, and Russia are independent of big business or that corporate pressure is benign. I am claiming that the situation is somewhat complicated and unpredictable, and there is room for strategic action. Each of the bullet points with which I began this post is a pressure point.

(See also “two doses of realism about democracy,” “what is corruption?,” and “putting facts, values, and strategies together: the case of the Human Development Index.”)