- Facebook33

- Twitter2

- Total 35

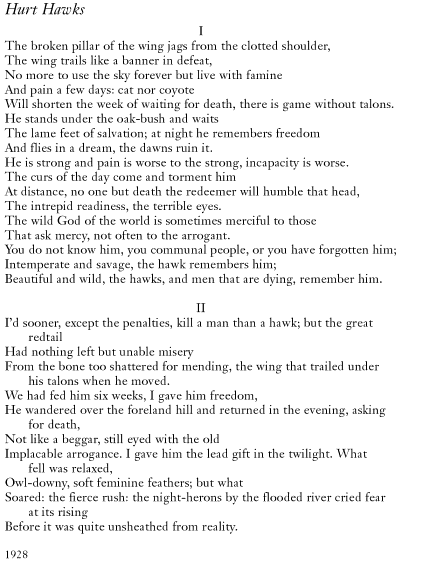

Robinson Jeffers’ son kept a wounded hawk as a pet for a few weeks in the 1920s. Jeffers wrote part 1 of this poem as a complete work before he killed the bird, adding part 2 later. It is famous for the line, “I’d sooner, except the penalties, kill a man than a hawk.” Since he did shoot the hawk, Jeffers is either very sorry about what he did or he doesn’t much care for human life.

Part 1 is descriptive and relatively impersonal. There is no first-person verb and no report of the narrator’s relationship to the bird. We are addressed (as “you communal people” who have forgotten “the wild God of the world”). We have access to the hawk’s inner life, knowing what he dreams of and what god he follows. The hawk does not understand us. I think “game without talons” refers to the food that the hawk is offered by his human captors, without his having to hunt it. The bird doesn’t grasp the meaning of the gift or the people’s intentions; he knows the meat by its bare description. “There is game without talons” is free indirect discourse, the hawk’s perspective taking over the narration.

Part 2 introduces the narrator’s voice and relates how he acted, in three steps: “We fed him for six weeks. … I gave him freedom. … I gave him the lead gift. …” Now the relationship between man and bird is central. The man tries to liberate the hawk, but you can’t give freedom to another creature. The bird returns asking for death. The man does what he is asked. At the end, he holds the dead bird, reduced to a soft object.

This poem has been criticized as didactic. In verse, you are supposed to show, not tell–or so the modernists insisted–but this poem makes general points in the voice of Robinson Jeffers. But is the author serious about the views he expresses here? For instance, did the hawk really ask for death? (Does a bird understand the concept of death as applied to itself, and can it know that a human being might put it out of its misery?) Is there actually a wild God that is merciful to the weak but not to the arrogant?

If the answer to any of these questions is negative, the poem starts to look much more complicated. We do not know what the bird thinks, only how it behaves. We have the testimony of the man about what he has seen and done, but we cannot take any of that for granted. The man has imputed ideas to the hawk and become the god of the bird’s small world. He is in complete control of what we know, just as he controls the animal’s life.

I read the poem not as a didactic statement about nature and life, but as as the unreliable report of a narrator who is unsure whether he should have killed his son’s pet hawk. That narrator is not necessarily Robinson Jeffers. We know that the poet really shot a hawk, but he might have done so without much emotion and derived the idea for a fictional story from the event. All we have is the story with its shifting, partial perspectives and ambiguities.

(By the way: why “Hurt Hawks” instead of “Hurt Hawk”? Why is the wild God capitalized?)