- Facebook58

- Twitter2

- Total 60

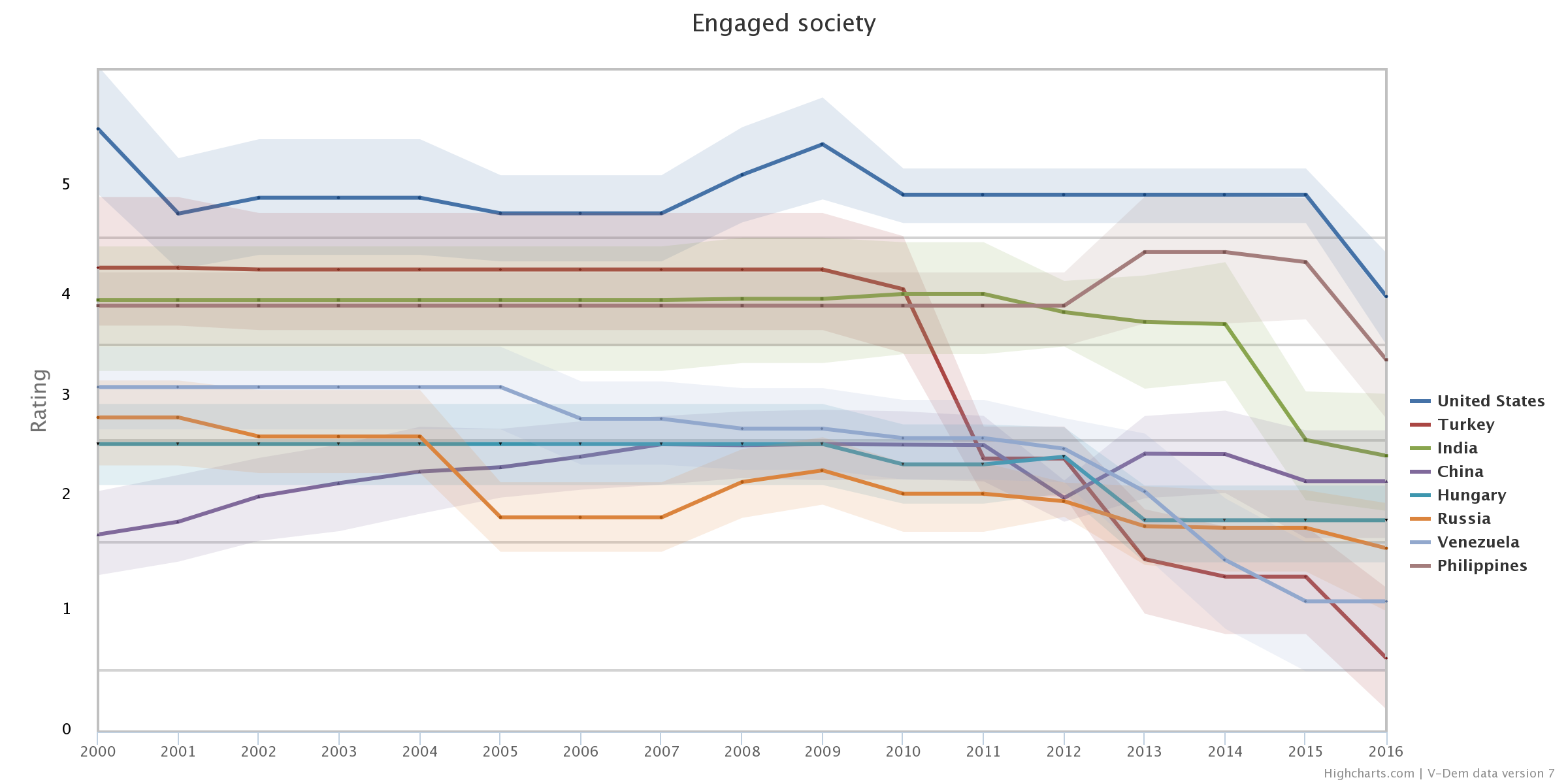

The Varieties of Democracy project asks 2,800 experts many questions about specific countries in specific years. One question is “When important policy changes are being considered, how wide and how independent are public deliberations?” The scale ranges from zero (“Public deliberation is never, or almost never allowed”) to 5 (“Large numbers of non-elite groups as well as ordinary people tend to discuss major policies among themselves, in the media, in associations or neighborhoods, or in the streets. Grass-roots deliberation is common and unconstrained”).

Below is a graph that shows the change in public deliberation (so measured) since 2000 for eight countries that I see as increasingly authoritarian. My choice of these countries is subjective. (Why not the Central African Republic, which Freedom House names as the single-biggest “backslider” on democracy in the world? Because I don’t know much about the CAR.) But of the countries that I selected in advance to serve as examples of growing authoritarianism, all but one showed declines in the V-Dem measure of broad public deliberation.

This pattern may seem self-evident or even tautological. Perhaps countries that are tending toward authoritarianism see less deliberation because authoritarianism is the opposite of deliberation. But I find the graph at least somewhat meaningful. At the core of authoritarianism is a reliance on powerful leaders who disdain constitutional limits. It’s possible for authoritarians to run a state even while “large numbers of people … discuss major policies among themselves, in the media, in associations or neighborhoods, or in the streets.” Some authoritarian states even choose to expand deliberative fora. For example, China’s Communist Party is implementing deliberative processes, which it probably sees as devices for blunting criticism and improving satisfaction with its deeply undemocratic regime (He & Warren 2017). Caroline W. Lee (2015) has argued that small-scale deliberation co-opts resistance in the USA, and Cristina Lafont (2017) worries that creating ideal deliberative fora can delegitimize regular democratic processes.

So the question arises whether authoritarianism is really contrary to deliberation at all. One might even suspect that the biggest threats to deliberation arise in mass capitalist societies, where corporate and partisan propaganda drown out reasoned conversation on poorly designed platforms, like Twitter.

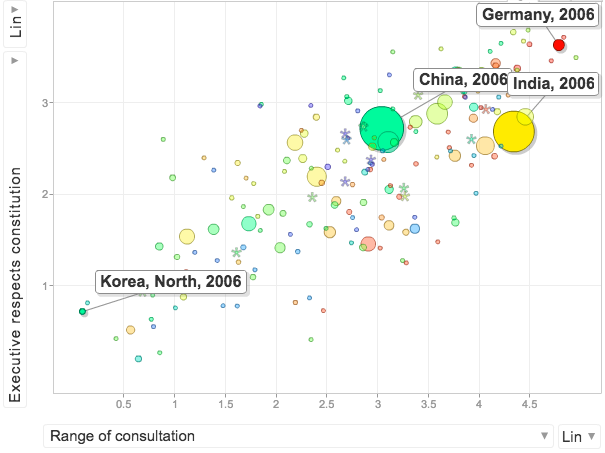

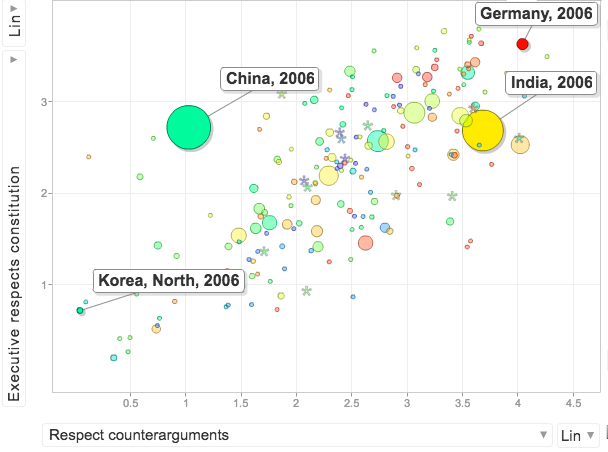

But this is partly an empirical question, and I do see evidence of a negative correlation between authoritarianism and deliberative values. Above I showed that countries well known for turning more authoritarian are also seeing less public deliberation. Below are two graphs showing a different relationship–between leaders’ respect for the constitution and the government’s tendency to consult a wide range of stakeholders. Again the source is V-Dem data, but unfortunately from 2006.

I take respect for the constitution as an inverse measure of authoritarianism, and consultation as a sign that a government wants to deliberate. The correlation is pretty clear. Most countries fall on a line between North Korea and Germany. India’s government consults more than China’s does. Neither respects its own constitution more than the other, but the Indian constitution is much better on civil liberties. The US is a circle between those two countries but a little higher up.

The next graph shows the same y-axis (respect for the constitution) plotted against the degree to which politicians respect counter-arguments. A high score on that measure means that they generally feel compelled to give explanations when they are challenged. Again, the line is defined by North Korea and Germany. On this plot, China is an outlier, showing decent respect for its own constitution but reluctance to consult diverse stakeholders.

Much more analysis could be done (and it would be better to use more recent data than 2006). Still, this seems to be evidence of a correlation–in practice, if not in theory–between respect for constitutional restraints and deliberative values. One reason may be that political leaders tend to model deliberation in societies where they also respect limits, and they fail to do so when they turn authoritarian. Or it could be that when publics are organized and motivated to demand discussion, they also block authoritarianism.

Sources: Baogang He & Mark E. Warren “Authoritarian Deliberation in China,” Daedalus, 146, 3, 155-166; Caroline W. Lee, Do-It-Yourself Democracy: The Rise of the Public Engagement Industry New York: Oxford University Press, 2015; Cristina Lafont, “Can Democracy be Deliberative & Participatory? The Democratic Case for Political Uses of Mini-Publics,” Daedalus 2017 146:3, 85-105.