It seems impossible to explain why Donald Trump won the 2016 election. For one thing, he lost the popular vote. Besides, a single election is an “n” of one with numerous contingent circumstances, in this case including the FBI’s last-minute intervention, Hillary Clinton’s gender, and the behavior of cable news. We often think of a cause as something that would yield a different result if it were changed. In this case, changing any of a dozen or more factors might have put Clinton in the White House.

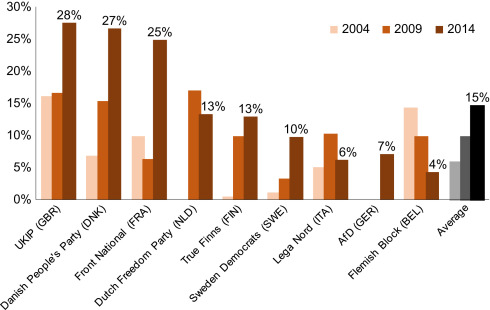

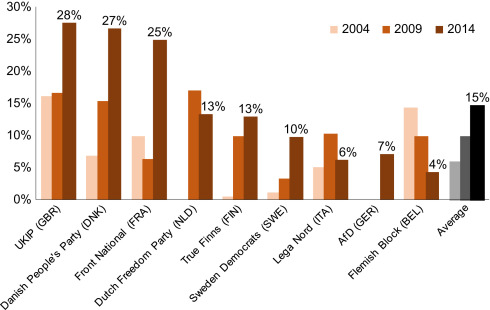

More valuable is to consider why authoritarian, illiberal nationalists either dominate or (like Trump) have narrowly missed winning majorities in many countries: at least in Austria, China, Hungary, India, Israel, the Philippines, Poland, Russia, South Africa, Turkey, and the United States–with England and France also looking at risk. Across the 34 OECD countries, true right-wing parties still capture only about 8 percent of total popular support, but that’s steadily up from five percent in the 1970s. This graph from Funke, Moritz & Schularick shows the recent shift in nine major European nations.

Vote Share for the Far Right Since 2004

At the global level, the “n” is much greater than one, and we can rule out certain explanations for the trends. For instance, in other counties, an authoritarian leader hasn’t replaced a person of color or defeated a female opponent.

I cannot estimate the relative impact of the following factors, but they seem plausible to me across the whole range of cases:

Oligarchy: Many of the authoritarian leaders are billionaires or closely associated with billionaires. Their supporters are personally wealthy individuals rather than multinational public companies, which are more comfortable with predictable centrists like Hillary Clinton. A billionaire can know political leaders personally, can trade wealth for influence, and can profit from disruptions in the larger economy. Several of the key billionaires are media personalities. I think some of them develop authoritarian expectations by being the barons of large private enterprises, within which their word is law. Billionaires have almost tripled their share of global GDP since 1996, and their inflation-adjusted total assets have risen by 7.5% annually over those two decades. They represent a global force that was absent in 1996.

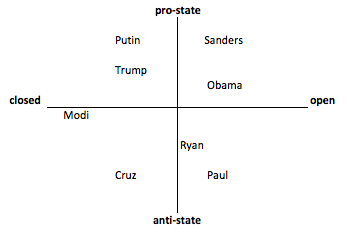

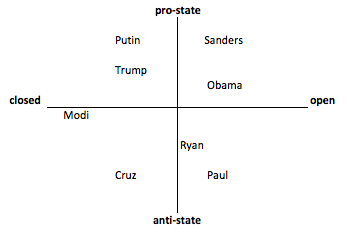

A gap in the ideological landscape: For this purpose, let’s categorize ideologies along two dimensions. They are either pro-state or anti-state/pro-market. And they either favor a narrowly defined ethnocultural group or they support diversity and globalism. I’ll call the latter spectrum closed versus open.

Since the 1950s, the dominant parties and movements in the wealthy democracies were all fairly open, at least in principle; the debate was about how much the state should intervene. We often thought of the US ideological spectrum as one-dimensional, from pro-state to pro-market, with everyone giving lip-service to openness. Some conservatives claimed to be pro-market and nationalist, but it’s not clear that that was a coherent position. The whole structure ignored the possibility of a pro-state, explicitly closed position. Like entrepreneurs who have discovered a market niche, authoritarian nationalists have filled the corner previously occupied by fascism. To be sure, Trump may govern like a market libertarian if he turns things over to Paul Ryan and contents himself with symbolic nationalism, but that’s not what he promised to do.

You would think that nationalist authoritarians wouldn’t cooperate much across international borders, because they are xenophobic. But there was a short-lived Fascist International in the 1930s, and we definitely see some coordination today.

Al Qaeda/ISIS: Before explaining why I think these terrorist organizations share causal responsibility for the global turn to authoritarianism, I want to stipulate that we are morally responsible for how we have responded to them. We did not have to invade Iraq, pass the Patriot Act, or turn Guantanamo into a prison. Those stupid and harmful acts are our responsibility as American citizens. Still, it seems both naive and misleading to omit the intentional acts of Al Qaeda and ISIS from our causal theory. They sought to provoke antidemocratic reactions, and they succeeded. An admired friend of mine recently summarized her qualitative research with Muslim teenagers in suburban New Jersey over the past decade, explaining that they have moved from a comfortable feeling of being Americans to a sense of vulnerability and alienation. This is an injustice that is up to remedy. But it struck me as a mistake not even to mention Al Qaeda as a major cause of the change. Osama bin Laden got what he wanted when he sent those planes into the Trade Towers. Although the US leadership of 2001 (including H. Clinton) proved monumentally stupid, Al Qaeda found a vulnerability that would have been hard to defend.

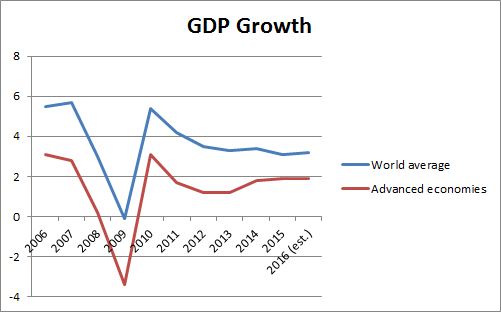

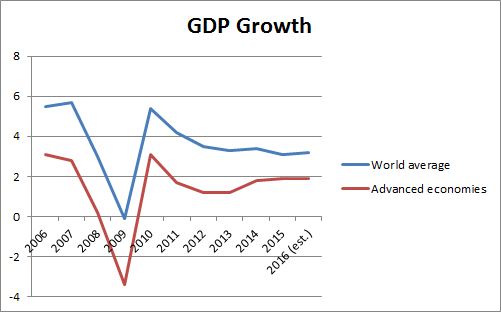

The 2007-8 financial crisis: Funke, Moritz & Schularick show pretty compellingly that voters shift to the far right after financial crises. This has been a pattern across many nations for at least a century. The 2007-8 collapse was an especially terrible one. It hit the advanced economies particularly hard, thus giving their voters a sense that they were losing comparative advantage as well as absolute wealth. It was followed by fiscal austerity that punished ordinary people, while no elites were held accountable for the trillions of dollars of waste and disruption. My sense is that Barack Obama got a pass from a majority of Americans because he wasn’t responsible at the time of the crisis, and he has been seen as laboring to repair the damage. But Hillary Clinton was part of the governing elite that was on duty when the fateful decisions were made.

Cultural backlash: Pippa Norris proposes that cultural liberalization (marriage equality, improving sexual equality, growing racial diversity, etc.). have produced a backlash rooted in the White working class of OECD countries. She clearly favors the trend of cultural liberalization and abhors the backlash, but a different take is Nancy Fraser‘s: people are rightly rejecting a form of “progressive neoliberalism” that unites “new social movements (feminism, anti-racism, multiculturalism, and LGBTQ rights)” with the cultural agendas of “high-end ‘symbolic’ and service-based business sectors (Wall Street, Silicon Valley, and Hollywood).” That is the coalition that delivers diversity in schools and workplaces along with “the weakening of unions, the decline of real wages, the increasing precarity of work, and the rise of the two–earner family in place of the defunct family wage.”

A hollowing out of democracy: People have died or placed themselves in terrible danger in the name of democracy and liberal values, whether on Omaha Beach or the Edmund Pettus Bridge. But an inspiring vision of democracy means more than the right to choose among professional politicians every few years. Even a call for equality isn’t inspiring enough, because how much should each of us care whether our share of power is as great as everyone else’s? Democracy must mean working together to create a better world.

Instead, the US rightwing has abandoned the sometimes inspiring pro-democratic rhetoric of Ronald Reagan to claim that we are not a democracy at all, but a republic. Similar rhetorical shifts away from democracy are evident in other countries as well. Meanwhile, the technocratic center presents democracy as a system of regular elections along with transparent information. Even defenders of the EU admit that it demonstrates a severe “democracy deficit.” Democratically governed associations, such as unions and congregationalist churches, are in decline. And several strands of the left are reflexively critical of any pro-democratic project that emerges in the US or elsewhere in the wealthy global North. People seem increasingly sophisticated about democracy’s drawbacks (misinformation, majority tyranny, cultural bias, etc.) and decreasingly inspired by its promise. That leaves the field open for explicitly illiberal and antidemocratic movements.