- Facebook339

- Total 339

Discussing Dewey in the Summer Institute of Civic Studies yesterday, I (and, I think, several colleagues) had the sudden recognition that American pragmatists tend not to deal with evil very persuasively. In The Public and its Problems, Dewey writes:

Nevertheless, the current has set steadily in one direction: toward democratic forms. That government exists to serve its community, and that this purpose cannot be achieved unless the community itself shares in selecting its governors and determining their policies, are a deposit of fact left, as far as we can see, permanently in the wake of doctrines and forms, however transitory the latter. They are not the whole of the democratic idea, but they express it in its political phase. Belief in this political aspect … marks a well-attested conclusion from historic facts. (p. 146)

Dewey’s idea is that we can’t justify processes like electing leaders a priori. There is no natural right to vote; it doesn’t depend on a social contract. Rather, it’s a “deposit of fact” left from human learning over many centuries. Voting exists because we have learned to vote. Fortunately, that process is progressive and beneficial: the current has steadily flowed toward democracy. It is crucial not to fetishize any given process or right, because we will come up with better ones later. When we think of documents like the Constitution, Dewey says, “the words ‘sacred’ and sanctity’ come readily to our lips” (pp. 169-70), interfering with our critical reasoning and our ability to learn from experience.

These words were published in 1927. About 14 million people were sentenced to the Gulag from 1929 to 1953. Auschwitz opened in 1940. The current was not exactly steady in the direction of democracy. Robert Zaretsky has a beautiful piece in today’s Times about how not being occupied during World War II made Americans–probably white Americans more than others–“stupid.” According to Zaretsky, Czeslaw Milosz was fairly indulgent of our stupidity, although he diagnosed it clearly. It is precisely the kind of foolishness suggested by the first sentence in Dewey’s quotation above.

What if we said the following instead? Human beings torture each other, enslave each other, carpet-bomb each other, and intentionally wipe out whole communities. This happens often. Enough: it has to stop. Translated into constitutional terms, “thou shalt not torture people” turns into a right to due process and rule of law. We must do our best to make such rights sacred and nonnegotiable. They are not literally sacred, in the sense that God or nature decreed them. But they are bulwarks against cruelty, which is the worst of us, to paraphrase Judith Shklar’s Liberalism of Fear. When everything is left open to experimentation and learning, people may spend hundreds of years “learning” that they can own other people or that Jews are blood-sucking parasites. We should rather treat as sacred and unamendable such passages as Article One of the German Constitution:

(1) Human dignity shall be inviolable. To respect and protect it shall be the duty of all state authority. (2) The German people therefore acknowledge inviolable and inalienable human rights as the basis of every community, of peace and of justice in the world.

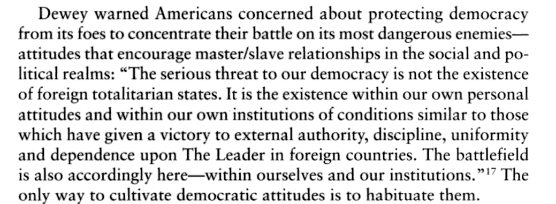

I think that there are pragmatist replies to this kind of liberalism, but I can’t be satisfied with them unless they explicitly invoke and address the problem of evil. I’m worried about this kind of theme in Dewey (ably summarized by John M. Savage in John Dewey’s Liberalism):

I’m all for cultivating democratic habits, but that’s not the only bulwark against tyranny. It’s also helpful to ban tyranny and to make that prohibition permanent.