- Facebook196

- Total 196

(Phoenix, AZ), While I am here today as a guest of Arizona State, I will give a version of the following talk:

The video summarizes my view of civic life in about 10 minutes. By “civic life,” I mean applying our minds, voices, and bodies to improving the world. We can do that alone, but inevitably civic life is collaborative, because individuals rarely achieve much alone and because we need other people’s opinions and perspectives to inform our goals and values.

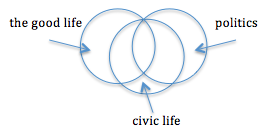

Civic life is important, but it is by no means the only important thing. It represents one circle in this Venn diagram, which also includes circles for politics–meaning all the ways that human beings govern ourselves and create a common world–and the good life.

In civic life, certain ways of interacting are possible and desirable. We can and should be highly interactive while we are in smallish groups dedicated to improving the world. We can be responsive to one another’s needs and opinions and strive act in concert.

But a good life should sometimes be solitary and inward-looking, or directed to nature or God instead of fellow citizens. And politics should sometimes involve competition instead of deliberation and cooperation. For instance, we want incumbent politicians to be regularly challenged by outsiders who criticize them and strive to unseat them. We don’t want incumbents to get too cozy with their challengers. The same is true of business competitors and contending attorneys.

In the video, I argue—and I strongly believe—that civic engagement can enrich our inner lives and offer us psychological and spiritual benefits. But so can non-civic activities, such as observing and appreciating nature, understanding and making art, or loving and caring for other people intimately. Although I think that the spiritual benefits of civic life are often overlooked—and improving our civic culture would strengthen those benefits—I still resist the argument that the good life equals civic engagement.

Here is a typically subtle case: I love to walk in the woods with my family and dog. Enjoying those loved ones in a natural setting is not a form of civic engagement. However, it is only thanks to the Massachusetts Audubon Society and our state government—and the individuals who work in or with those organizations—that the woods have been preserved and opened for us to use. The worthy activity (a family walk) is not civic, yet it depends upon other people’s civic engagement. Still, it’s far too narrow a view of nature and of intimate personal relations to reduce them to products of civic life.

By the same token, civic life doesn’t exhaust politics or offer adequate means to improve politics. Large, impersonal institutions—such as markets and companies, governments and armies, and scientific and technical disciplines—play leading roles in 21st century politics. You and I have limited leverage over these institutions. We can form opinions about what they should do, but those opinions do not always imply meaningful actions for us to take.

If the institution in question is the United States government, I have a tiny but greater-than-zero form of leverage in the form of my vote. If the institution is Coca-Cola, I can decide whether to purchase its products or not. Allocating votes and money are worthwhile acts but hardly constitute a robust civic life. And if the institution in question is the Chinese Government or the market for oil rigs, my leverage approaches zero. In the video, I say that citizens ask, “What should we do?” rather than “What should be done?” But sometimes reasonable people realize that something should be done and yet cannot find anything to do about it themselves. That is the zone of politics that lies outside of civic life in the Venn diagram above.

In the video and almost all my work, I emphasize that “small groups of thoughtful and committed citizens” have the capacity and responsibility to change large systems. I began my professional career helping to advocate for political reform as a research associate at Common Cause, and while I worked there, Common Cause was losing its membership base due to the shrinkage of American civil society that Robert Putnam would soon diagnose in “Bowling Alone” (1995). I came to think that American politics was corrupt because citizens were not adequately organized and active, and I have spent the subsequent two decades working on civic engagement as a precondition for better government. Still, political reform eludes us in the face of hostile Supreme Court decisions, technological developments, and tenacious political opposition. When reform does come, it may be because of a massive scandal or a well-placed leader, not directly because of active citizens. In some other countries and in global markets, the scope for civic life is even narrower than it is in the US.

To discount the importance of citizens in politics is cynical, but to imagine that intentional civic action is all of politics is naive. To the extent we can, we should work to expand the overlap, so that civic life is more politically influential as well as more spiritually rewarding. But I think we will always be left with two hard questions (among others):

- How should we think and act and feel when bad systems are genuinely beyond our control? The Stoic and classical Indian answer was: seek equanimity and acceptance. Epictetus advised: “For if the essence of the good lies in what we can achieve, then there is no space for ill-will or jealousy. Rather, for yourself, don’t strive to be a general or an office-holder or a leader/consul, but to be free. The only road to that is contempt for things not in your power [XIX].” I am unsatisfied with that answer, because I think we have responsibilities to the world even when we cannot see a direct way to address its problems. But what are those responsibilities, exactly? And …

- When an aspect of the good life conflicts with civic responsibilities, how should we choose between them?