- Facebook410

- Twitter1

- Total 411

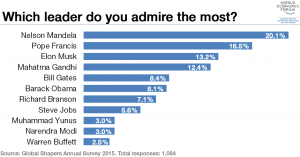

In a discussion with undergraduates a week ago, the familiar question arose: Why don’t social movements have great leaders any more? One could dispute the premise, arguing that we do have social movement leaders today and that we romanticize the past when we forget how divisive–even within their own movements–most leaders have always been. Still, I think the students were onto something when they posed this question. Here are the leaders whom young people around the world admired the most in 2015:

The two people who could clearly be classified as leaders of social movements are dead. Of the rest, five are business leaders and two are elected officials in very large and influential democracies. Only Pope Francis and Muhammad Yunus could be described as leaders in civil society, and neither is a classic example of a social movement participant. Meanwhile, some highly prominent current movements–the Arab Spring, #Occupy, Black Lives Matter–are known for their reluctance to anoint leaders.

I’d propose three theses:

1. “Apex” leaders are assets to social movements, even today.

Leaders who become famous for their participation in social movements are useful. They symbolize the movement’s objectives and its spirit in human form. They can use their prestige to mediate disagreements within the movement. And they are available to negotiate with outside powers. It’s hard to imagine the victory of Solidarity in Poland or the Freedom Movement in South Africa if Lech Walesa and Nelson Mandela hadn’t ultimately been able to sit down across a table from the regime and work out a deal.

2. Social movements make leaders, more than leaders make social movements.

There is a widespread view that very charismatic and visionary leaders call social movements into being. Perhaps that has happened a few times, but the reverse seems much more typical. Social movements identify individuals who have potential to lead. They offer them opportunities to develop leadership skills and expand their reputations. Often, movement members must cajole the prospective leader into playing that role. They then deliberately construct a reputation for their leader, for the consumption of outsiders.

A classic example is Martin Luther King’s ascent to leadership in Montgomery ca. 1954. As Taylor Branch tells the story in Parting the Waters, King moved to Montgomery with ambitions to participate in civil right activism. Although still a young man, he had been groomed for leadership in his father’s Atlanta congregation and at Morehouse College, where President Benjamin E. Mays was a prophetic leader who had gone to India to meet Gandhi. These institutions, already pillars of the nascent Civil Rights Movement, had developed King’s skills and imparted an overwhelming sense of obligation. In his new city of Montgomery, he took deliberate steps to enter the black leadership, giving a “stirring speech” at the NAACP and joining its executive committee (which, needless to say, already existed). The Montgomery Bus Boycott was started by other people, mainly women, who used finely honed techniques to implement a carefully designed plan. King was recruited to join the effort after it had begun and was then nominated to be the president of the leadership team.

Idealists would say afterward that King’s gifts would made him the obvious choice. Realists would scoff at this, saying that King was not very well known, and that his chief asset was a lack of debts or enemies. Cynics would say that the establishment preachers stepped back for King only because they saw more blame and danger ahead than glory (Branch, p. 137).

And–I would add–everyone assumed that a male reverend doctor would make a more palatable leader than Rosa Parks, a woman without a college degree who had been “focused for almost two decades on white men’s sexual aggression and violence against black women” and who had challenged the Montgomery bus system because of systematic sexual harassment against black female riders. Hers was not an agenda that would appeal to socially conservative African Americans or white liberals.

So King was chosen. This is not to detract from his personal gifts, but even those came in part from his training within the movement. The other church leaders in Montgomery identified King’s extraordinary talents, gave him an opportunity to use them, and helped develop his national persona. It’s in that sense that the Civil Rights Movement made Dr. King, more than the reverse.

3. Good social movements hold their leaders accountable and limit their powers.

We live in a time of “strong” leaders. China’s Xi Jinping, India’s Narendra Modi, Russia’s Vladimir Putin, and Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s alone preside over a contiguous bloc of countries whose populations approach three billion. Each of these men has consolidated power and projects a macho image. None is particularly accountable. Meanwhile, as I mentioned earlier, we see social movements develop without leaders at all.

The best cases surely lie in between. They are movements with “apex” leaders whose powers are circumscribed and who are held constantly accountable. Again, King is a great example. His main formal role was president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which “differed from organizations such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), in that it operated as an umbrella organization of affiliates.” So King was not only accountable to a board, but the organization he led depended on churches’ voluntary and revocable decisions to join. He had no formal power over SNCC or NAACP, let alone the Nation of Islam. Indeed, these groups fairly often competed. To the extent that he was the leader of the whole Civil Rights Movement, he had to earn that standing by constantly serving the grassroots base. It’s that specific kind of leadership that seems especially lacking today.

See also the real Rosa Parks; is the Sanders campaign a movement?; and how to respond to a leader’s call for civic renewal.