- Facebook18

- Total 18

There is a thriving market for generalized portraits of Millennials, whether positive or negative. These are just some examples from my own bookshelf:

There are interesting things to say about this generation–and about generational change as a phenomenon. But if you look closely, the picture is pretty complicated. Differences among people born at the same time are usually much greater than differences among generations–a point that my colleagues and I have emphasized in much of our work. Also, trends over time rarely point to sharp and stable differences among generations.

So many beliefs and behaviors have been measured regularly over 40 years that it’s hard to generalize, but I’ll pick two trends just to illustrate the complexity.

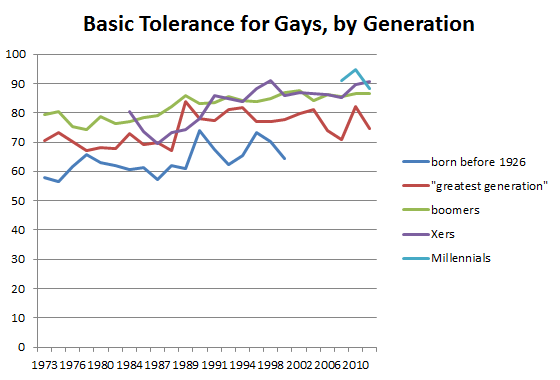

First, it is widely believed, and reasonably so, that attitudes toward gays are generational, changing (for the better, in my view) with each new age cohort. The longest relevant survey time-series that I know is from the General Social Survey, which asks whether a list of types of people should be allowed to speak in one’s community. One person on the list is an “admitted homosexual” man–the terminology itself reflecting a more prejudiced era. The question is imperfect for our purposes because it conflates attitudes toward free speech with views of homosexuality. (Someone might be homophobic yet a First Amendment absolutist.) Nevertheless, the pattern is interesting.

Each generation does enter the adult population with successively more positive views of speech by a gay man–until the Xers, who are no different from, and perhaps slightly less tolerant than, the Boomers who preceded them. Each generation grows slightly more tolerant over its life course, but the main reason for increasing tolerance in the population as a whole is generational replacement. A nation of Millenials will support speech by gay men much more than a nation of people born before World War II.

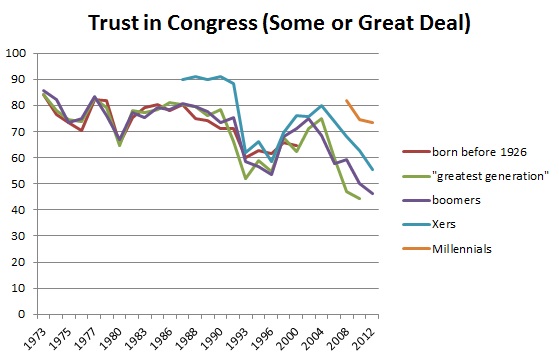

It is also widely believed that younger generations have less trust or confidence in government. This general construct can be measured in many ways. One useful time-series is a GSS question about confidence in the US Congress to do the right thing.

In this case, I see lots of change but little evidence of a generational thesis. The older three generations move in lockstep. Their confidence falls sharply after the Reagan/Tip O’Neil era, recovers from the Gingrich speakership and late Clinton era through 9/11, and falls subsequently. They are all seeing the same political situation and reacting similarly. Generation X does start at a much higher level in the 1980s. They also rise more in the middle of the George W. Bush administration. I would chalk this up to partisanship (since Xers have been somewhat more Republican than other cohorts), but the question concerns trust in Congress, and the Xers’ early trust is in a Democratic House. As for the Millennials, they enter with higher confidence than their parents show at the present time, but with similar views to older generations when those were young.

Overall, I would not describe this graph as evidence of a generational story but as an illustration of a “period effect”: everyone, regardless of age or birth year, has similar views of the current situation in Congress, and everyone is prone to fairly rapid changes depending on their perception of recent news from DC.

See also: a generational shift leftward?; support for abortion rights: a generational story; tolerance & generational change; talking about this generation; and young people and trust in government.