- Facebook758

- Threads

- Bluesky

- Total 758

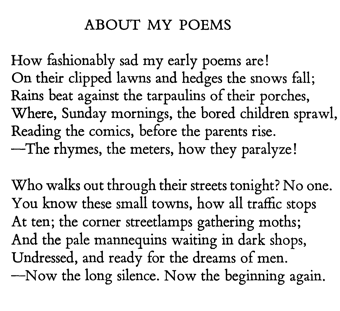

Donald Justice, “About My Poems,” from Poetry magazine, March 1965:

The poet appears as a critic of his own “early” (immature) verse that is “fashionably sad” and whose regular rhymes and meters “paralyze.” Nonetheless, he offers a rhymed, rhythmically regular poem composed of nothing but sad metaphors. They are so sad, in fact, that they overwhelm the wryness of the opening. This poem is the opposite of a shaggy-dog joke: not a humorless story that ends with a funny twist, but a punchline that introduces a moving story.

“Fashionable” has at least three senses. It can mean faddish, of temporary appeal. Nothing depicted in the poem is fashionable in that way, and some of the objects are precisely the opposite. For instance, a naked mannequin is a human figure without anything temporary and new to clothe it. A second meaning is “popular.” Moths swarming under streetlamps represent fashion, in that sense. A third meaning is contrived, artificial, or fashioned. The aesthetic of a small town is fashionable, by that third definition. Justice asks in what sense his own poem is “fashionable.” Is it artificial (with its heightened poetic forms)? Does it manipulate its readers into predictable emotions, like moths by a streetlamp? Is it modish in some way?

To what, exactly, does Justice compare his “early poems”? They have clipped lawns, porches, and streets. Under their porches, children sprawl; in their streets at night, mannequins wait. No single thing has both lawns and display windows. The poems are not analogous to one object, but all resemble small-town, bourgeois, American life in a mode of stillness and languor.

It is not so bad to be a bored child on a rainy Sunday morning: that might evoke nostalgia. It is worse to be a naked mannequin waiting to be desired. But either way, one is paralyzed and inactive, caught in a “long silence.”

The poem, however, is not silent. It speaks of these things. And people walk the poem’s streets–we do, when we read it. The poem is not like the mannequins; it absorbs the attention. Just when we are fully absorbed (perhaps “paralyzed” by the mood), the poet says, “Now the beginning again.” We’re sent back to his opening line about his own “fashionably sad” poems. We have been reading modern lyric verse in a conventional way. But then it is hard not to keep reading and become nostalgically sad again.