- Facebook28

- Total 28

I think I’m noticing more and more people using “I” instead of “me” when it’s the object of a verb, as in “Please give it to Joe and I.” This may have started as an over-correction. Kids are taught not to use “me” as the subject of a sentence (as in “Me and Joe are going to the store”) and they generalize it to never use “me” if another name is involved. After all, it’s a cognitive task to figure out whether to say, “she and I” or “her and me,” depending on the function of the phrase in the sentence. Perhaps a new rule is gradually arising that you always say “I” when there’s another name in the phrase. I must say that I don’t like the change, because it reflects a lack of consciousness about how the language is structured; but languages change, and I can get used to it.

If you search Google right now for “to you and I” and “to you and me,” you’ll see 181 million of the former phrase and 36.9 million of the latter, almost a 5-to-1 ratio in favor of the choice that grammar books would declare to be incorrect. (“To you and I” is always incorrect if you apply the traditional and official rule that an indirect object takes “me.”) This ratio suggests that the grammarians are losing a struggle against linguistic evolution.

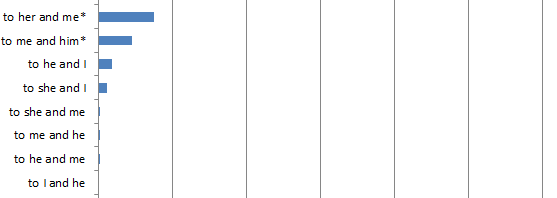

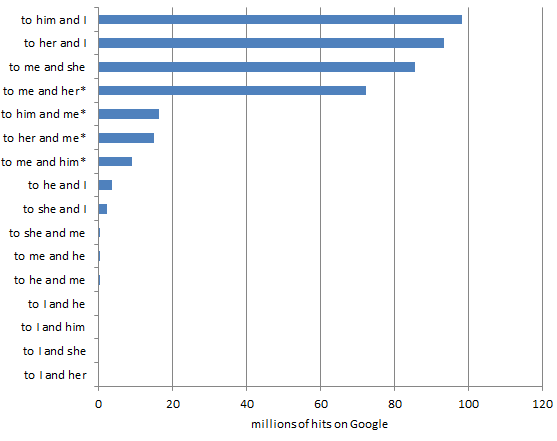

Here are the frequencies of all possible combinations involving I or me and he/him she/her. The most popular are the incorrect options “to him and I” and “to her and I.” Interestingly, “to me and she” is very popular, but its grammatical equivalent, “to me and he” is rare. The correct options are less popular, and there are several conceivable combinations, such as “to I and he,” that no one uses.

*grammatically correct

The question is whether this is really a trend. I know of one device for tracking changes in language over the long span: Google’s nGram tool. It has a major limitation: the corpus is limited to published books. Most books are professionally edited, and thus much less likely than ordinary speech to violate grammatical rules–except insofar as they report dialogue.

Even given that limitation, the trend is interesting. “To you and me” outnumbers “to you and I” in books, in contrast to the World Wide Web as a whole. But “to you and I” is not very uncommon, and it has increased as a share of all the text in published books. It can literally not be found in any book published in 1800. One period of increase was between 1880 and 1920. Another was after the year 2000. But “to you and me” has also rapidly increased since 2000, and the ratio in favor of the grammatically normative version has actually increased in books.