- Facebook249

- Threads

- Bluesky

- Total 249

It is good that Americans disagree about civic education. We are a free and diverse people who care about youth and the future of our republic. Agreement is not to be expected and could even be problematic. The question is whether we can disagree well while also giving our students an appropriate array of choices that they can assess for themselves.

I think there are almost as many ideas about the ideal approach to civics as there are people in the debate, and it is a mistake to assume that the field has polarized into just two or a few camps. Many individuals hold nuanced and complex views.

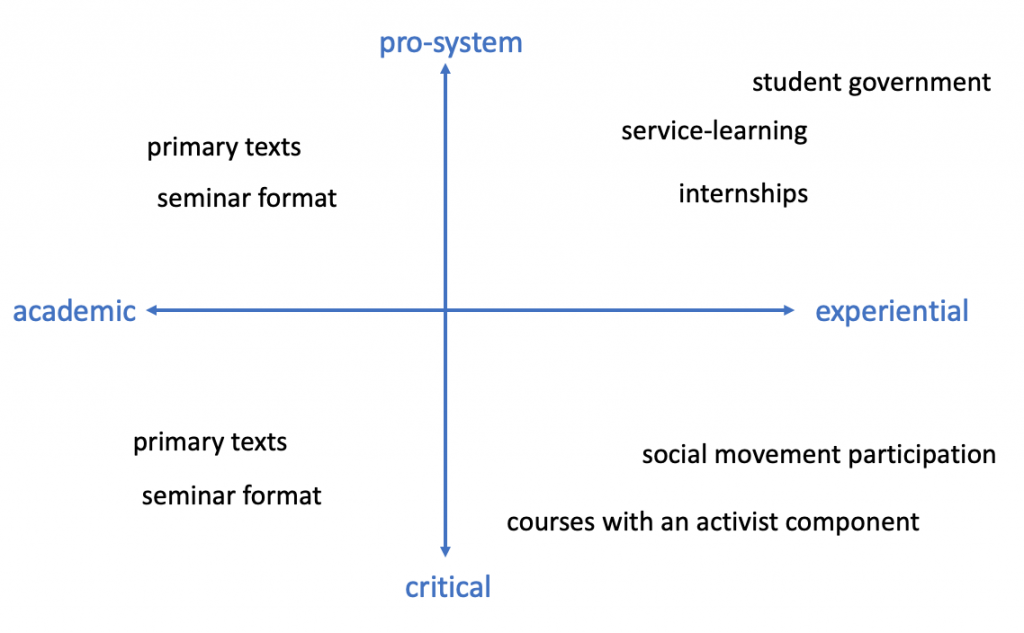

If I had to try to categorize views, I definitely would not use one continuum from left to right. I see two different axes that may help to organize the debate–as long as one remembers that hardly anyone chooses an extreme point on either continuum, and many see value across the whole map.

The vertical axis runs from favorable to critical of the US political system and society. Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee recently tweeted that his state’s schools will teach “unapologetic American exceptionalism.” In this context, “exceptional” doesn’t usually mean atypical; it means better. That places Gov. Lee pretty close to the top of my graph. Someone who wants students to focus on historical and current injustices would fall near the bottom.

The horizontal axis runs from classroom-based work (reading, discussing, and writing about texts) to experiential learning. It may also reflect a debate about whether knowledge or skills are the most important outcomes. Lee added, “By prioritizing civics education in TN schools, we are raising a generation of young people who are knowledgeable in American history and confident in navigating their civic responsibilities.” He seems to be open to engagement as an outcome, so maybe he would support the whole top half of my graph.

These two axes are distinct and orthogonal. The most common forms of experiential civics–approaches like service-learning and student government–are often pro-system. They belong above the middle of the chart. In the Positive Youth Development field, service-learning is understood as “contributing positively to self, family, community, and, ultimately, civil society” (Chung & McBride 2015). Service-learning may also encompass critical reflection about systems (Mitchell 2008), but I think the critical aspect has been rare and often superficial.

On the other hand, if you really want to teach some version of critical theory in a K-12 classroom, you are probably interested in assigning and discussing texts. (That is why it is called “theory.”) So you likely fall the left of the middle of my chart–on the same side as the people who want to assign classical texts that they appreciate. The pedagogy is similar; the debate is about which texts to assign, which topics to discuss, and which interpretive lenses to use. Meanwhile, many of us strive to assign texts with diverse perspectives and cultivate a robust discussion within the classroom.

For what it’s worth, my own emphasis is on learning how to build and manage associations. I’d use an academic pedagogy (reading, writing, and discussing texts, data, and models) for a pragmatic purpose: making civil society work. I’d let the students decide the ultimate objectives of their own associations. This approach implies a canon of texts (Alexis de Tocqueville, Gandhi, Robert Michels, Jane Addams, Mary Parker Follett, Saul Alinsky, Bayard Rustin, Ella Baker, Jenny Mansbridge, Elinor Ostrom …) that is neither pro- nor anti-system, as a whole.

I would never claim that this is the only important approach, but I think it is undersupplied.

See also: NAEd Report on Educating for Civic Reasoning and Discourse; an overview of civic education in the USA and Germany; The Educating for American Democracy Roadmap; etc.