It is inexcusable to vote for Donald Trump, a cruel and incompetent charlatan. To imply that anyone is justified in voting for him sets a patronizingly low standard. Our fellow Americans can do better than that.

At the same time, Trump’s demographic base consists of people–predominantly, white working-class Americans–who must be active, enthusiastic members of a progressive coalition. If they fall outside that coalition, real progress is impossible. I think the solution lies not in developing policies that would benefit the white working class, nor in devising new messages to attract them, but in strategies that allow them to win genuine power. I interpret the Trump phenomenon, in part, as a symptom of their powerlessness.

Class and the current partisan alignment

It is normal for partisan support to reflect demographics. What is unprecedented is the precise way that the US population has split in this decade. Basically, the Obama/Clinton coalition is the upper end of the economic scale plus people of color. The Trump coalition is the working class minus people of color.

College attainment is both a precondition and an indicator of middle-class status in contemporary America. In a poll taken between the conventions, Hillary Clinton led college-educated whites by 5 points, but she trailed Trump among whites who don’t have college degrees by 39 points: 62% to 23%. That gap must have set a record, but it was not wildly out of line with other recent results. Peter Beinart has assembled much more evidence for what he calls a “class inversion.” Note that Clinton also leads Trump by 16 points among Fortune 500 CEOs. In Silicon Valley, she led Trump by 64% to 20% in a poll last spring. Meanwhile, she leads by huge margins among all racial/ethnic groups other than Whites.

Chris Arnade reports from two parts of metro Cleveland, OH: white working-class Parma and African American Central Cleveland, which is one of the poorest communities in the nation. In Parma, Arnade writes,

Trump voters want respect. They want respect for their long hours of work that risks their bodies, for the hands caught in vices, backs wrenched by weights, and knees torn. They want respect because they are doing dangerous work, but their pay has been flat for decades.

They want respect because they haven’t just lost economically, but also socially. When they turn on the TV, they see their way of life being mocked and made fun of as nothing but uneducated white trash.

With Trump, they are finding someone who gives them respect. He talks their language, addresses their concerns

In Central, “the need for respect, the feeling of being left behind, is [also] well-understood.” But everyone there favors Clinton, and Arnade thinks that’s because “people feel they do have a political voice. They believe the Democrats are working for them, they might not like everything about the party, they might not fully like the results, but the party is respecting their concerns. [The] overwhelming political concern I heard had little to do with anything other than electing Hillary, and stopping Trump.”

I think this passage overstates African Americans’ satisfaction with the Democrats. Peniel Joseph describes “multiple strategic and substantive displays of multiracial unity” inside the Democratic National Convention. But “outside the convention hall Black Lives Matter demonstrators begged to differ, protesting the Democratic Party as an entity held corporate hostage to financial institutions whose candidate Hillary Clinton they say backed criminal justice and welfare reform that have had a devastating impact on poor black communities.” Jordie Davies writes that 2016 presents the choice between “a demagogue [Trump] and more of the same complacent, anti-black policies [from Clinton].”

But to the extent that the African American voters of Central Cleveland trust the Democratic Party, it may be because they observe Black people wielding actual power within the party. The President is African American. One in four delegates to the DNC was Black, and more than half were people of color. This is not because the party has given African Americans anything, but because Black people have won elections at all levels from local party officers to the presidency. So African Americans are at the table, even if they are often outgunned by wealthier interests and outnumbered.

Meanwhile, if you identify as working class, you will see virtually no one like you wielding power in either party. You may notice a few politicians of working-class origins, but almost everyone who influences either party is now a white-collar professional. Michael Podhorzer, the AFL-CIO’s political director, says, “We would argue that most of the political class comes from the same background whether it is Democrats or Republicans and that all politicians lack a kind of authenticity with working-class voters.”

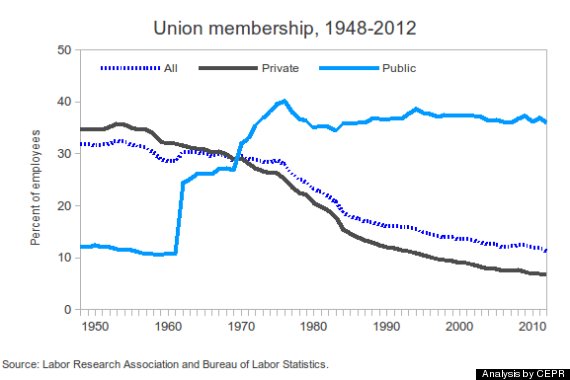

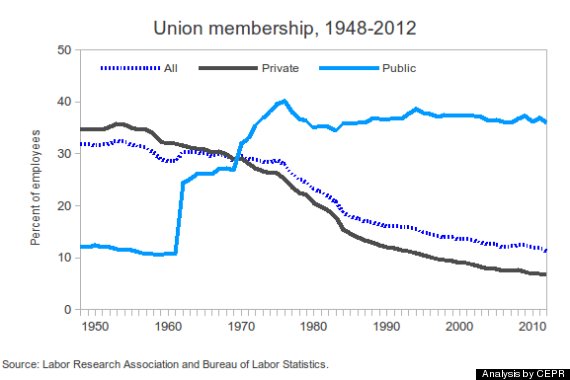

Of course, union staff are also professionals, but they owe their jobs to rank-and-file members. Unfortunately, their place is increasingly marginal. Although five union leaders spoke on the first day of the DNC, none spoke in prime time, and two of them represented college-educated public employees. It would be easy to overlook industrial unions in the Democratic Party coalition, and this is why:

Private sector workers simply aren’t in unions anymore. Andrade begins his depiction of white working class Parma with the key point. It is “defined by auto factories: massive edifices to another era that now sit mostly idle. Scattered throughout are union halls, like UAW Local 1005, which is mostly empty, holding only a few cars.” I think the UAW’s empty parking lot is an image of political powerlessness; and powerlessness breeds Trumpism.

The new demographic split influences cultural institutions as well politics. For instance, Tufts University has always had, and must have, conservative students and faculty. It should be a place for productive debate between liberals and conservatives (and others). But I have not personally encountered anyone here who supports Trump. That makes sense, because Tufts is a college; its purpose is to produce college graduates. We admit students from working-class homes, but we strive to prepare them all for adulthood in the middle class. That’s what they pay us for. We also strive–albeit imperfectly–for racial, ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity. Consequently, everyone who graduates from Tufts enters the demographic categories that are currently lined up behind Clinton.

The need for organizing

The New Deal/Great Society coalition–always highly imperfect, unequal, and fractious–consisted of the working class (of all races/ethnicities) plus wealthier people who saw themselves as minorities, including religious minorities. In settings like national political campaigns, the various elements of the progressive coalition had to learn from and negotiate with each other. Together, they achieved some progress.

Today’s Democrats are typically stronger than Republicans on civil rights, especially rhetorically and in cases when addressing injustice won’t cost upper-income whites anything. For instance, as a white man with a PhD, I gain nothing from unjust policing or mass incarceration; I’d be better off without both. Racial diversity also improves my life, as long as I retain my own place in my job and neighborhood. Further, Democrats are prone to fund education, partly because they endorse principles (like equality and freedom) that education may advance; partly because today’s Democrats are often meritocrats and technocrats who treat success in school as an indicator of a good life; and partly because their coalition includes teachers and professors, who are paid to educate.

But Democrats won’t make more than marginal commitments to addressing the profound destruction of de-industrialization, rising deference to wealth and capital, or the economic situation of working class people (trends summarized here). That is because the working class is outnumbered in the Democratic coalition. Meanwhile, the Trump coalition could support policies that benefited the working class–note his embrace of a higher minimum wage and his opposition to trade liberalization–but since his coalition has been built to exclude people of color, it is terrible on civil rights and diversity issues. And Trump offers no real solutions even for working-class white people.

Democrats should enact policies for working class communities suffering from declining real income, falling life-expectancy, opioid addiction, and fragmenting families. At this moment, I think their policies are much better than the Republicans’, and it’s worth emphasizing that contrast. But beneath policy is politics, and there is no reason to believe that a coalition dependent on the upper class will consistently support policies that make a real difference to people in the lower class, especially when a majority of the lower class is voting for the other party. I’ve shown (here and here) that today’s most educated Americans are liberal but not egalitarian. The Democrats can obtain a majority coalition by offering neoliberalism plus diversity, and that is the likely long-term outcome.

An even deeper problem is that you cannot confer respect on someone else by giving him a better deal. So even if the Democrats enacted stronger policies to benefit the working class–infrastructure spending would be a good example–that wouldn’t make working-class people feel that they had a genuine seat at the table. They must design and enact policies to feel empowered. In turn, that requires organizations that can compel attention.

Solutions

Unions are one essential form of organization. The Democratic Party Platform says, “A major factor in the 40-year decline in the middle class is that the rights of workers to bargain collectively for better wages and benefits have been under attack at all levels.” The Platform promises: “Democrats will make it easier for workers, public and private, to exercise their right to organize and join unions. We will fight to pass laws that direct the National Labor Relations Board to certify a union if a simple majority of eligible workers sign valid authorization cards, as well as laws that bring companies to the negotiating table.”

I am not sure to what extent such reforms would restore the fortunes of organized labor, because another major obstacle is the changing nature of work; but we should certainly demand that the Democrats honor this promise.

In addition to unions, there are also community organizing groups that have genuine roots in white working class communities. Check out Kentuckians for the Commonwealth or the Maine People’s Alliance, among many others.

There is also cultural work to be done: the creation of stories, images, music, and other media that inspire working people politically. It’s striking that the Great Recession of 2007-8 never produced a cultural response comparable to the 1930s: no iconic images or anthems. I think a satisfactory narrative must address racism, because that is both morally important and necessary for building a coalition that spans races. However, the main rhetorical emphasis cannot be the privilege of being white, because “privileged” is a poor description of people who are being made superfluous in the 21st century labor market. Besides, I can’t think of any case when people have given up advantages because someone has drawn their attention to them. Told that they are privileged, people are much more likely to realize what they ought to protect.

Nor can the main tone be resentment, a sense of victimhood, or reactionary nostalgia, because nothing good comes of that. The story must evoke genuine pride and must look forward rather than back.

Since an identity as “white” is deeply problematic, we should be looking for alternatives: pride in local geographical communities or specific subcultures, plus a definition of “American” that is proudly inclusive rather than fearfully divisive.

Leonard Cohen probably isn’t the guy to reach a big enough audience, but we might take hints from his song “Democracy” (brilliantly analyzed by Laura Grattan). For instance, here he juxtaposes Otis Redding with a Chevy ad, goes inside a home and over to the Middle East with our troops:

It’s coming from the silence

on the dock of the bay,

from the brave, the bold, the battered

heart of Chevrolet:

Democracy is coming to the U.S.A.

It’s coming from the sorrow in the street,

the holy places where the races meet;

from the homicidal bitchin’

that goes down in every kitchen

to determine who will serve and who will eat.

From the wells of disappointment

where the women kneel to pray

for the grace of God in the desert here

and the desert far away:

Democracy is coming to the U.S.A.

This is a version of progressive democratic patriotism. The Democrats didn’t do a bad job of evoking such ideas at their Convention. I think the issue is the credibility of Democratic politicians as messengers.

In any event, messages and narratives must rest on real organizations, and the working class needs more of those. Otherwise, to quote Hannah Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism (h/t Josh Miller), we will face a combination of “superfluous wealth”–think of Donald Trump– and “superfluous men” (working class people without capital or advanced skills). As in the early 1900s, the superfluous could again form “a mass of people … free of all principles and so large numerically that they [can] be used only by imperialist politicians and inspired only by racist doctrines” (pp. 156-7). We know how that story ends.

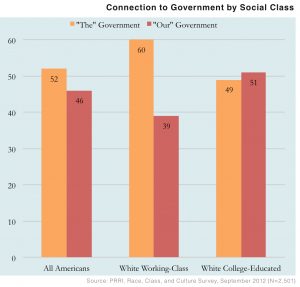

recent long post, I argued that one reason white working class Americans are alienated from government is that they lack the productive political power that comes from organizations, such as political parties that rely on ordinary members, and unions. Moreover, because of the weakness of such organizations, white working class people are simply not visible in positions of power. A few leaders can rightly say that they started life in the working class, but almost by definition, they are now all well-paid and highly educated professionals.

recent long post, I argued that one reason white working class Americans are alienated from government is that they lack the productive political power that comes from organizations, such as political parties that rely on ordinary members, and unions. Moreover, because of the weakness of such organizations, white working class people are simply not visible in positions of power. A few leaders can rightly say that they started life in the working class, but almost by definition, they are now all well-paid and highly educated professionals.

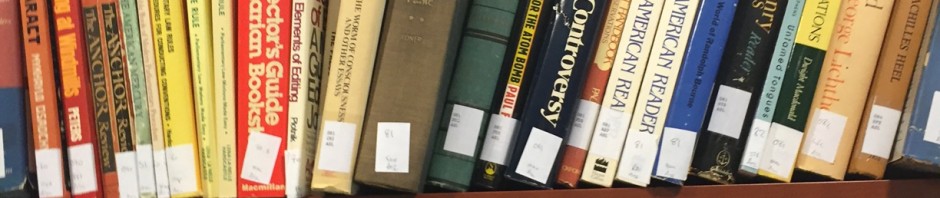

This is part of the library of Albert Shanker (1928-77), which lines the walls of the conference room of the Albert Shanker Institute, which is inside the American Federation of Teachers’ Building in Washington. I was there earlier today. It seems fitting that such a library should rest in the heart of the AFT, exemplifying the long, rich, and living tradition of intellectual life within the labor movement (and—importantly—outside of universities).

This is part of the library of Albert Shanker (1928-77), which lines the walls of the conference room of the Albert Shanker Institute, which is inside the American Federation of Teachers’ Building in Washington. I was there earlier today. It seems fitting that such a library should rest in the heart of the AFT, exemplifying the long, rich, and living tradition of intellectual life within the labor movement (and—importantly—outside of universities).