- Facebook128

- Threads

- Bluesky

- Total 128

Following Foucault, let’s use the word “spirituality” for this cluster of ideas: What is true (i.e., most actually real) is the same as what is most right and most beautiful. To know this truth requires being a better person; truth comes to one whose mind or soul is in an appropriate condition. In turn, perceiving the truth improves the perceiver.

Several modes of spirituality have been taught (and sometimes combined). In the ecstatic mode, the seeker loves truth, longs for it, and expects ecstasy from its attainment. In the ascetic mode, the seeker renounces ordinary desires and comforts to merit truth. In the diligent mode, the seeker labors for years at ritual or memorization–or literal labor–until rewarded with truth. In the mode of faith, the seeker ignores the evidence of senses and the pull of desires to believe in what is not directly known.

Seekers may be solitary or may benefit from community, but the spiritual seeker’s encounter with the truth is ultimately private and direct.

Although spirituality encompasses–and sometimes encourages–tensions, struggles, and paradoxes, the whole package is neat. Truth, goodness, and beauty cohere; improving the soul yields knowledge, which further improves the soul.

Now consider science, viewed as this cluster of ideas: There is a real world, and it is strictly a domain of causes and effects (“nature”) which is not moral or beautiful in itself. Goodness and beauty are our subjective categories. In seeking to know nature, we are hampered by biases. However, we can use impersonal techniques and tools, such as careful quantitative measurement, to counter our biases. Moral and aesthetic preferences are among the many biases that interfere with our grasp of nature if we don’t control for them.

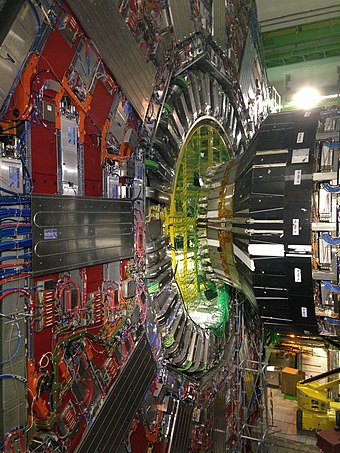

Since the truth is replicable, it will be known just the same by a bad person and a good one. Instead of putting ourselves in maximally direct contact with the truth in order to improve or save ourselves, we should generally put instruments in direct contact with nature and review the data that they yield. (Instruments may be as simple as rulers or as elaborate as particle accelerators). The data should then be made available to as many people–and for as many uses–as possible. Whether these uses are good is not a scientific question, and possibly not an answerable one.

Are hybrids possible? Some famous scientists have testified to their own spiritual inclinations. Einstein is the most obvious example: “Everyone who is seriously involved in the pursuit of science becomes convinced that a spirit is manifest in the laws of the universe.” Such combinations shouldn’t surprise us, since both the spiritual and the scientific traditions are prominent and influential. The same person can be affected by both. Having a spiritual side may help some scientists to be happy and may motivate them to be devoted scientists.

However, other scientists are successful without being happy or are happily motivated by non-spiritual factors, such as fame, power, competitiveness, or even wealth. If spirituality correlates with scientific acumen, that is an empirical generalization, not a law–and it may not even be a valid generalization. Claims that science and spirituality are intrinsically or logically related are romantic and naive. Their logics (as described above) are incompatible. Some individual scientists manage to hold them together, but some individuals also combine kindness to family with cruelty on the battlefield, or love of country with love of money. We can contain multitudes.

Still, it is important to avoid the Hobson’s Choice of either science or spirituality. We need a robust discussion of what is right, both for individuals and for institutions and societies. That discussion is not helped by the widespread scientific premise that answers to the question “What is right?” are merely subjective.

This premise doesn’t damage the conversation as much as you’d expect. Plenty of people claim that moral beliefs are subjective and relative yet strongly endorse actual moral principles and exchange reasons about them. A student last semester wrote an impassioned paper in favor of affordable housing, and ended it: “Overall, what makes a policy ‘good’ is completely subjective–in this paper, however, I have argued that in my view, …” No harm done; again, we contain multitudes. But there is harm at a more institutional level, where we fail to invest in the normative disciplines and in public deliberation while we pour resources into applied science.

Science does have an ethic of its own, including the obligation to make findings public, the principle of blindness to scientists’ personal identities, and cosmopolitanism. The fact that actual science violates these principles does not invalidate them; it just means there is important work to be done.

But the ethics of science is insufficient. Even if science worked exactly as advertised, it would still have little to say about what makes a good life or a good society, particularly for non-scientists.

Here’s where spirituality offers resources. Especially important is its insistence that you probably won’t be good just because you know what is good, intellectually. Since people are habitual and reflective creatures, we need methods for self-improvement–things like rituals.

The problem, for me, is spirituality’s premise that truth and goodness cohere. I see no reason to assume that, and therefore no reason to presume that what is good is also true. If that premise is false, then the tools of science are likely more reliable than those of spirituality–if our goal is to understand nature. But understanding nature should not be our only goal.

See also: adding democracy to Robert Merton’s CUDOS norms for science; is all truth scientific truth?; Philosophy as a Way of Life (on Pierre Hadot); Foucault’s spiritual exercises; notes on the social role of science: 1. the example of fetal ultrasounds; and science, UFOs, and the diminishment of humankind.