- Facebook45

- Twitter2

- Total 47

I think of a “teaching case” as a true story that culminates in a difficult decision that has confronted an individual or group. The decision is typically difficult because of conflicting values, incomplete information, and unpredictable outcomes. A teaching case is useful as a prompt for discussion and to teach the disposition of acting wisely under uncertainty, or phronesis. I especially like cases in which groups must decide collectively, because those stories allow attention to the dynamics of group decision-making. Here is a selection of such “civic” cases: https://sites.tufts.edu/civicstudies/case-studies/

This semester, I have been co-teaching a course with Jennifer Howe Peace, who has extensive experience not only leading discussions based on teaching cases but also assigning students to write such cases. We did just that this fall. Each of our students selected a real-world situation, conducted research, wrote a 2-3 page case about it, and led a discussion.

I recommend this pedagogy for teaching the following essential civic skills:

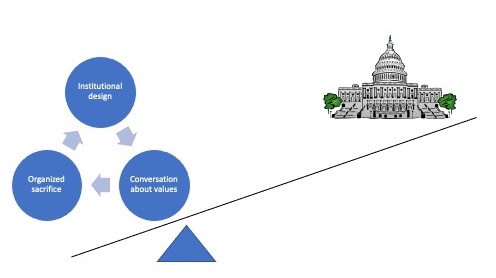

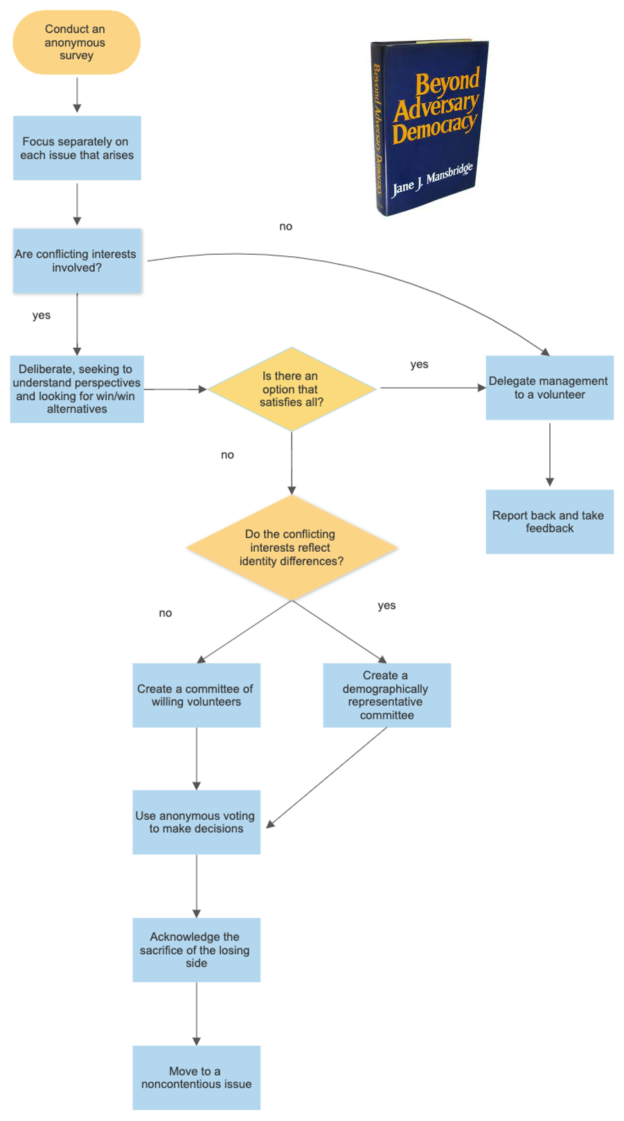

- Identifying decisions worthy of discussion. Actual groups often overlook or evade decisions that they should discuss and spend time on matters that don’t require deliberation. (See “a flowchart for collective decision-making in democratic small groups.”) Writing a case means choosing a topic that should be discussed.

- Identifying the tradeoffs and other difficulties, such as incomplete information and unpredictability.

- Identifying who is in a position to make which choices. It is a costly distraction to ask what someone should do if they can’t do it. A good written case centers on one or more protagonists who are able to choose.

- Deciding when to start and end the story. This side of the Big Bang, every story has emerged from many previous ones. The web of human interaction has no beginning. The choice of when to start a written story frames it for readers; it is an act of judgment. (For instance, does the story of the USA begin in 1492, 1619, 1776, 1789 …?) Writing a case teaches the skill and ethics of picking beginnings and endings well.

- Eliciting interest and attention. A well-written case makes its readers interested. Getting people’s attention is a basic civic skill.

See also: A Festival of Cases, June 24; three new cases for learning how to organize and make collective change; practical lessons from classic cases of civil disobedience; Levinson and Fay, Dilemmas of Educational Ethics; Bent Flyvbjerg and social science as phronesis;