- Facebook146

- Total 146

(Washington, DC) My colleagues Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg and Felicia Sullivan coined the phrase “civic deserts” to name places where there are few or no opportunities to be active and constructive participants in civic life. The analogy is to “food deserts”–geographical communities where there is little or no nutritious food for sale. You can still be an active citizen in a civic desert, just as you can grow vegetables in your back yard; it’s just that the whole burden falls on you.

Today at the National Conference on Citizenship, we are releasing Civic Deserts: America’s Civic Health Challenge by Matthew N. Atwell, John Bridgeland, and me. It’s a 36-page report that documents the declining opportunities for civic engagement in America. John Bridgeland and Robert Putnam also write about it today in a PBS opinion piece.

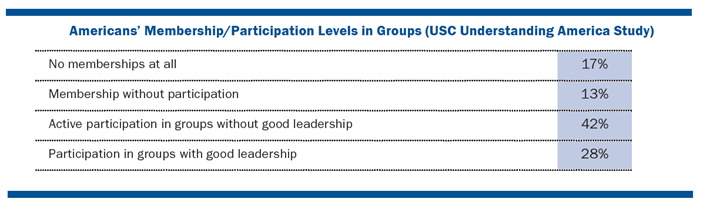

This is an example of a table from the report:

Thanks to friends at USC’s Center for Economic and Social Research, we were able to ask a large, representative sample of Americans whether they belonged to various kinds of groups; if so, whether they participated actively in any of them; and if so, whether they thought that the group’s leaders (a) usually did what they promised and (b) usually tried to serve and include all the members. It turns out that only 28% of adult Americans actively belong to groups whose leaders are accountable and inclusive. That statistic does not tell us how much geographical space is taken up by civic deserts, but it suggests that they are common. And the historical data implies that civic engagement used to be much more widespread.

I separately formed a hypothesis that lacking direct, personal experience with good leadership would make a person more tolerant of the leadership style of Donald J. Trump, controlling for one’s political ideology. In other words, given two people who agree with Trump on issues, the one without experience of good local leadership would be more supportive of Trump as a leader. This was testable with the USC data, which includes a whole battery of questions about ideology, issues, and Trump. My hypothesis turned out not to be true: partisanship and media choice seem to explain opinions of the current president almost completely, and experience in groups adds no explanatory power. Still, I think there may be a more circuitous story about civic deserts as a cause of Trump’s victory: the decline of civic associations increases the power of partisan heuristics and ideological media. Even if that hypothesis is also false, civic deserts are still a problem, because civic engagement benefits health, economic development, safety, education, and good government.

See also: The Hollowing Out of US Democracy (my blog post for USC); Mitigating the Negative Consequences of Living in Civic Deserts – What Digital Media Can (and have yet to) Do (a new CIRCLE article); America needs big ideas to heal our divides. Here are three by Bridgeland and Putnam; and the power of the NRA in an age of civic deserts.