- Facebook30

- Total 30

CIRCLE has released its framework for “growing voters” (as an alternative to mobilizing people just in time to vote one way or the other in an election). This short slide deck is a summary; much more information is here.

CIRCLE has released its framework for “growing voters” (as an alternative to mobilizing people just in time to vote one way or the other in an election). This short slide deck is a summary; much more information is here.

Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound, lines 19-35, in my amateur translation:

Prometheus, you will always suffer under

One tyrant or another, uncomforted:

That’s the price of befriending people.

A god, you didn’t fear the rage of gods

When you gave mortals the forbidden gifts.

The penalty: you’ll always guard this rock,

This awful rock. No sleep, no rest; you can’t even

Move your leg. You just sing out your anguish

To no effect. Prometheus, it is a hard thing

To change the mind of the king of the gods.

For every new ruler is harsh and cruel.

And according to Google TranslateTM:

Arthovoulos Themidis absolutely,

Nearby of dissolvable copper

I use human ice cream

It is neither the voice nor the brute form

Light, constant flame retardant

you have to pay for flowers. Tied up

lei a variety of hidden hides,

thunderstorms if the sun again:

This is a bad thing

bury you: à à à ù ù ù

this is what I give to the philanthropic way.

God forbid, not even for the balloons

Honorable Mention I Am Out Of Trial.

There are no stone guards here

Arthostadin, Cleft, the knee flexor:

a lot of good people and good people.

Type: Two grams of unpleasant brakes.

You left me alone in the new hold.

Announcing his reelection campaign, Senator Ben Sasse (R-NE) made two claims about civic education:

1) “What’s at stake in 2020 is nothing less than a choice between American civics and socialism,” Sasse said. ‘”Those are the stakes.”

2) Sasse drew a direct connection between American teenagers not knowing civics and the fact that polling data today suggests that nearly 40% of Americans under 30 believe the First Amendment might be harmful.”

Sasse also quoted Reagan to the effect that “freedom is always one generation away from extinction. [It] is not passed along in the bloodstream—it has to be taught.” The main theme of his reelection launch was civics, at least according to his website.

The Post’s Jennifer Rubin thinks this is just another example of a Republican politician debased by Donald Trump. She calls Sasse’s speech a “pathetic spectacle” and thinks he should know better. Perhaps, but my style is to take people seriously, and Sasse is generally a serious thinker.

Besides, he is not alone in arguing that countering a socialist revival (presumably embodied by a few junior members of the House of Representatives and a presidential primary candidate) is a reason to restore civic education. Such arguments will affect those of us who work for civics, changing the political context for our efforts.

We also confront claims that what is at stake in 2020 is nothing less than a choice between American civics and Donald Trump. One (or conceivably both) of these arguments might be right, but both raise partisan sensitivities in their opponents and thereby complicate the politics in state legislatures and elsewhere.

We can all agree with Sen. Sasse that principles of freedom must be taught and that low support for the First Amendment is troubling. The most alarming evidence of decline comes from Yascha Mounk, although I raise some doubts about his study here.

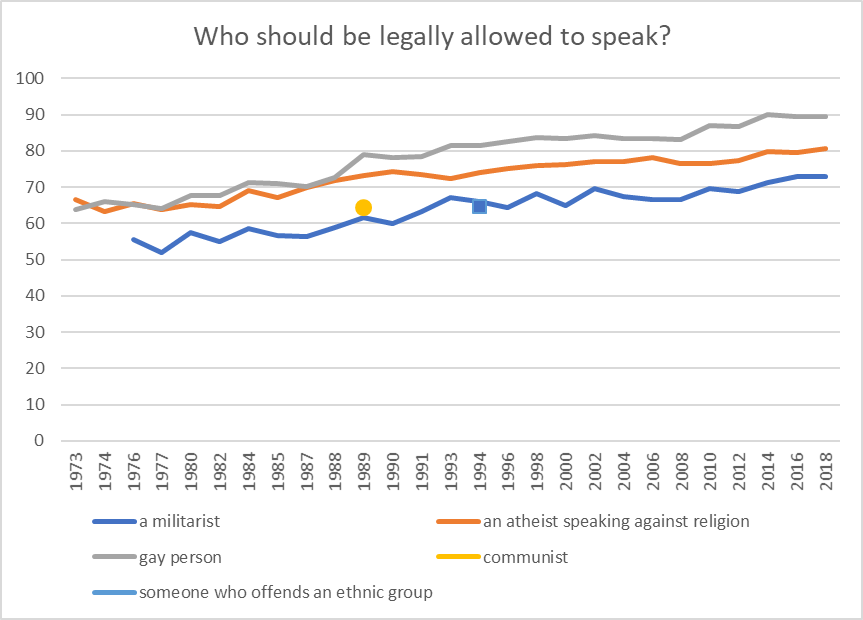

The General Social Survey has asked Americans whether various categories of people “should be allowed to speak.” The trends have generally risen over time. Americans have never been consistent supporters of the First Amendment, but they have generally become more willing to tolerate various categories of disfavored speakers. In 2019, Knight found that 58% of college students favored legally permitting “hate speech.” Perhaps this result reflects too little support for the First Amendment, but a similar proportion of adults in 1994 wanted to permit speech that (merely) offended another ethnic group. I think free speech requires constant attention, but I don’t see evidence of decline.

The controversial part of Sasse’s statement is not his support for the First Amendment or other civil liberties. It’s his contrast between “American civics” and “socialism.” That contrast raises the question of what those two categories mean. Sasse seems to suggest that support for the First Amendment and socialism are incompatible, but that is definitely not true; there is a long tradition of socialists who have also been strong supporters of free speech.

“Democratic socialism is committed both to a freedom of speech that does not recoil from dissent, and to the freedom to organize independent trade unions, women’s groups, political parties, and other social movements. We are committed to a freedom of religion and conscience that acknowledges the rights of those for whom spiritual concerns are central and the rights of those who reject organized religion.”

“Where We Stand,” Democratic Socialists of America

On one view, socialism is about economics, and it’s a matter of degree. Perhaps the metric is the proportion of GDP managed by the state (between 15% and 25% in the USA ever since 1955). The US is more socialistic than it was in 1900 and a bit less so than Germany is today. But then one must decide whether the political economy established by the New Deal and the Great Society–since it is somewhat socialist–is compatible or not with the ideas that we should impart in “American civics.”

James Ceasar has distinguished between “civic education,” which by definition supports a regime, and “political education,” which aims to change the regime. For him, the educational reforms of the Progressive Movement, multiculturalism, and global education are three examples of political, not civic, education, because they have aimed to change what he identifies as the American regime. (Here “regime” doesn’t have a negative connotation; it just means the core features of a political order.)

My question is why our regime must be defined by the dominant constitutional theory of 1900. I’d read our current regime as (more or less) a multicultural welfare state, in which case an education that promotes the American regime should favor those values. Education that aims to delegitimize the welfare state is political, not civic, in the 21st century. It is a form of politics with a reactionary intent. Maybe the education that John Dewey and other Progressives promoted was political in their own time, but because they won victories as political reformers, now their ideas have become the civic ones (in Ceasar’s sense)–the ideas that bolster the present system. And if the present system is partly socialist, then “American civics” is partly socialist.

On a different view, socialism is something that we have never seen in America. It refers to policies that are more radical than, say, Social Security or the Environmental Protection Act, because these laws have passed constitutional muster and have become part of the American tradition. Some socialists would concur that Social Security and the EPA are not socialistic to a satisfactory degree; they want a lot more. (But such people are scarce in the USA.)

Sometimes in this debate, people say that students should learn to prize “limited” government. I would only observe that governments that are avowedly socialist can be very careful about limits–constitutional, legal, and democratic. The Scandinavian democracies are excellent examples. They endorse the idea of the Rechtsstaat (a government under law) even as they tax and spend at relatively high rates.

Moreover, the limits set by the US Constitution can be compatible with much more socialism than we have today. No one disputes, for example, that Congress has the constitutional authority to raise income tax rates by a lot and to spend a lot more on social welfare programs. So limits per se aren’t really the issue; the question is what policies we should choose.

A third view might be that civic education, properly understood, encourages students to be less individualistic, less acquisitive, and more concerned with the common good than they would be otherwise. Therefore, it may strengthen support for the kinds of policies that strong conservatives like Sen. Sasse would call socialistic. In that case, civics and socialism are not opposed; they go together. To argue this point well, I think you would have to define “socialism” very broadly, so that it encompasses Great Society liberalism, Christian and other faith-based communitarianism, and mild social-democratic reforms as well as more radical proposals.

On yet a different view, students should not be taught any substantive political views in public schools. Schools should be committed to impartiality and should respect the individual rights of students to form their own opinions. (Impartiality is also a safeguard against the regime’s propagandizing in its own favor.) Students should learn about socialism, libertarianism, constitutional originalism, feminism, critical race theory, environmentalism, and other doctrines and should be equipped to make their own choices.

The problem here is that schools inevitably impart values, and probably should instill the values that create and sustain a fundamentally decent regime. Even studying a range of political ideologies reflects a political stance (some form of liberalism). So, if we must teach values, then are the values of democratic socialism opposed to the legitimate American regime, or part of it now, or better than the regime–or is this all a matter that students should debate?

My own view, for what it’s worth, is that socialism names a basket of policy options that have been part of the American political debate since the 188os and that students should critically assess as part of their civic educations. They may also reflect on the other traditions, apart from socialism, that have animated the American left. And certainly they should understand and asses various forms of conservative thought. The values that Donald Trump represents have equally deep (or deeper) historical roots in America, but some of his values are contrary to the fundamental aspirations of the regime and should be marginalized in “American civics” worthy of the name.

See also civic education in the year of Trump: neutrality vs. civil courage; Bernie Sanders runs on the 1948 Democratic Party Platform; the Nordic model; What is the appropriate role for higher education at a time of social activism?

Moral Foundations theory is an important body of research that has generated significant findings. It belongs to a somewhat larger category of research about morality that has these features:

Despite my interest in learning from the specific findings of Moral Foundations research, I harbor many objections, summarized here. In this post, I would like to elaborate on one concern.

We human beings make individual judgments about cases and decisions. That’s what the data-collection of Moral Foundations Theory models. But we do many other things that also shape values. For instance, we buy things, which causes more of those things to be made and sold. We participate in bureaucratic institutions that manage themselves through chains of command, policies, and files. We join and quit groups. And we govern by making laws and policies at all levels.

As Owen Flanagan writes in The Geography of Morals (2016), “Moral stage theory conceives moral decision-making individualistically. The dilemmas are to be solved by singleton agents. This is ecologically unrealistic. Committees at hospitals decide policies on organ allocation; government agencies deliberate about monetary policy; officers deliberate about costs and benefits of military operations; and friends talk to friends about tough decisions.”

I’ll focus on political decisions, although we should also consider markets, bureaucracies, friendships, scientific disciplines, and other social forms.

People make laws and other rules to prohibit, regulate, tax, subsidize, and mandate various behaviors. These rules directly influence how we act and may also affect our values, if only because many of us display the Moral Foundation of “Authority.”

One might think that rules and laws are made by people who implement their moral judgments, which are influenced by their individual Moral Foundations. Laws would then simply be aggregated Moral Foundations.

Not so, for these reasons:

For these reasons, empirical moral psychology cannot stand on its own without institutional/political analysis. Moral Foundations Theory is strongest when it aims to predict how people will individually react to a situation that raises issues so general that it resembles the problems that confronted our prehistoric ancestors on the savanna. The theory is least helpful for explaining why the same group of people might change its stance toward a specific topic, as we see with sexual orientation since 1969.

See also Jonathan Haidt’s six foundations of morality; an alternative to Moral Foundations Theory; moral thinking is a network, not a foundation with a superstructure; and against methodological individualism.