You may or may not be interested in games: playing them, designing them, or analyzing them with the tools of game theory. It is certainly understandable if games are not your thing. However, I believe that everyone should develop the skill of understanding interpersonal situations in terms of the choices and consequences that confront every actor, which is the essence of game theory.

This is a way of detecting problems that you might be able to fix. It is also a way to be more fair. Too often, we analyze situations in terms of the choices that confront us and the results that will befall us if we make any choice. We see other people as doing the right or the wrong thing, from our perspective. It is important to step away from that first-person view and assess the choices–and the costs and benefits–that confront everyone. Then their behavior may seem more reasonable, and the root of the problem may lie in the situation, not in the other people’s values.

When used as models of real life, games simplify and abstract. That is both a limitation and a huge advantage: a model can clarify important problems and patterns that may be hidden in the real world’s complexity.

Games do not presume that the players are selfish; in fact, altruists can get tangled up with coordination problems that games model well. Nor do games assume that people have full information or act rationally; uncertainty, randomness, and error can be built in.

Games do model situations in which people or other entities (e.g., animals, companies, nations) make separate choices, and the outcome results from the interaction of their decisions. Games are not very helpful for modeling other kinds of situations. One important form of civic action that they do not model well is a discussion about what is right (and why). Exchanging opinions and reasons isn’t well illuminated by a game. Therefore, I do not think that civic actors should only learn from games, yet game theory is a useful skill.

One way to introduce game theory is to play a game and reflect on how it works as a model.

Almost identical lesson plans can be found all over the Internet for a classroom game that models the Tragedy of the Commons using Goldfish crackers. I’m not sure who deserves the authorial credit for designing this lesson in the first place, but I have adopted it for several different classes and will share my current design.

Materials: goldfish crackers (“fish”); plastic bowls (“lakes”); and forks (as tools for fishing).

Each group of four people should sit in a circle around its lake, which contains nine fish to start. Players “fish” by removing the goldfish from the bowl with a fork. All groups fish for 15 seconds while the instructor keeps time. Then students put down their forks and the fish “reproduce”: each fish left in the lake produces two offspring, up to a total population of 16, which is the carrying capacity of the lake. Then you repeat fishing for another season until either the seasons are over or the fish run out.

I do not explain the goal or what counts as winning, because that will vary in interesting ways.

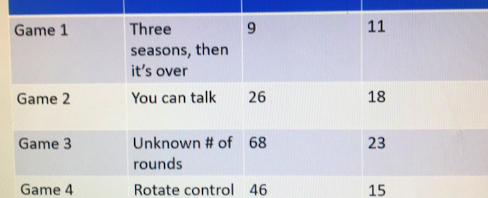

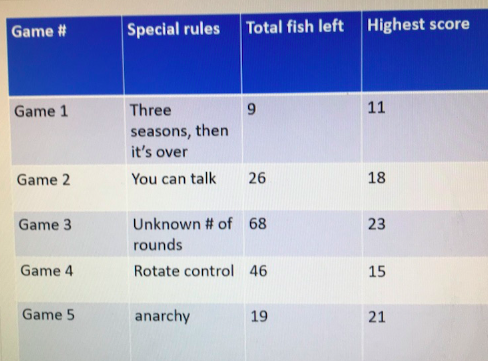

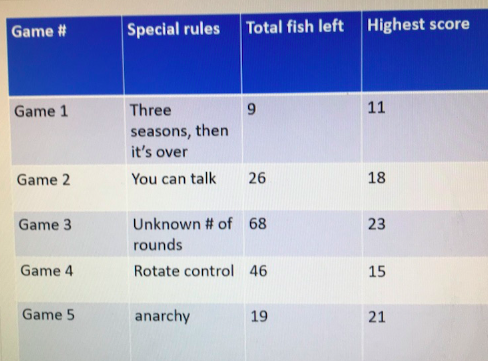

Each round has different rules.

- We play three seasons without talking at all.

- We play three seasons and may talk before the game begins and during it.

- Each group plays an unannounced number of seasons before I stop them. They may talk.

- We play three seasons silently, and each group rotates one fisher at a time. That person may spend as little or as much time as she likes. As long as she holds her fork, the others must wait.

- We play using game 2 rules, except students may take fish from any table.

I keep track of the largest number of fish collected by any individual in each game and the number of fish left in the whole room at the end of each game.

Below are the results from yesterday’s game, with 52 Tufts undergrads. Note that 68 fish were left when the number of seasons was unknown and students could talk. That is more than seven times more fish than survived in the first game, with a known number of seasons and no ability to communicate orally.

Questions for discussion:

- Did we observe “tragedies,” or not?

- When we did not, why not? What solutions did groups come up with?

- What were individuals trying to achieve? (Responses will likely vary: obtaining the most fish, trying to be fair, trying to look like nice people, learning by experimenting with different tactics.)

- Were your objectives affected by your perception of what other players were trying to achieve? (A norm can be understood as a shared sense of the goal.)

- What is the optimal solution? (Students should consider: maximizing the number of fish consumed, or the number of fish preserved at the end, and/or equity among the players. Other proposals may also emerge.)

- What parameters are included in the game? (Responses should include: attributes of the physical world; attributes of the community; official rules; and rules-in-use.)

- How realistic is the scenario? What is it a realistic model of?

- What assumptions does it make? How might those differ in reality? For instance, what if we played with $100 bills instead of Goldfish crackers?

- Why did everyone follow the instructor’s rules? Why not just grab the Goldfish?

- To what extent did additional rules emerge in practice? Is it realistic that people followed rules?

- In general, is it helpful to model a society using games? What assumptions does a game model make? (Selfishness?) What might a game not model well?

See also: evolution, game theory, and the morality of modern human beings; thoughts about game theory; and game theory and the fiscal cliff (ii).