We are heading overseas; back to the US and online on January 2.

Monthly Archives: December 2017

sorting out human welfare, equity and mobility

- Facebook150

- Total 150

Here are three distinct goals that you might pursue if you see education as a means to improve a society. All three are plausible, but they can conflict, and I think we should sort out where we stand on them.

- Improving lives. What constitutes a better life is contested, as is the question of how a population’s welfare should be aggregated to produce a score for a whole society. The Human Development Index includes such components as mean life expectancy at birth and “mean of years of schooling for adults.” You might think that what counts is not these averages but the minima: how much life, education, safety, health (etc.) does the worst-off stratum get? Their circumstances can improve with balanced and humane economic development. Arguably, the worst-off 20 percent of Americans are better off than Queen Elizabeth I was in 1600, because you’d rather have clean running water in your house than any number of smelly and disease-carrying servants. But our minimum is still not very good, since some Americans sleep on grates or are warehoused in pretrial detention facilities because they can’t afford bail.

- Equity. By this I just mean the difference between the top and the bottom, e.g., the GINI coefficient, although one might consider more factors besides income. Algeria and Sweden have almost identical levels of equity (GINI coefficients of 27.2 and 27.6, respectively), but Sweden is much wealthier, with 3.3 times as much GNP per capita as Algeria has.

- Mobility. This means the chance that someone born at a relatively low level in the socioeconomic distribution will rise to a relatively high level. By definition, that means that someone else must fall. (Or one person could fall halfway as far, and a second person could fall the other half way, to make room for the person who rises all the way up.) By definition, mobility is zero-sum, being measured as the odds of moving up or down percentile ranks. If everyone moves up, that’s #1 (an increase in aggregate welfare), not a sign of mobility.

These three goals can come apart. For example, equity coincides with very poor human development when everyone is starving together. Sweden has high human development and high equity but not much mobility: Swedish families who had noble surnames in the 17th century still predominate among the top income percentiles. It’s just that it doesn’t matter as much that you’re at the bottom in Sweden, because the least off do OK there.

To be sure, the best-off countries in the world tend to be more equitable and prosperous, and there’s a long list of very poor countries that are also highly unequal and (I guess) have little mobility. That pattern could suggest that the path to higher development requires equity. But that’s a contingent, empirical hypothesis, unlikely to be true across the board, and the goals are not the same.

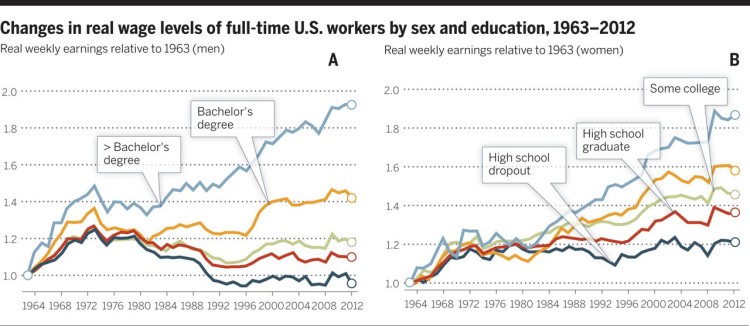

For proponents and analysts of education, the difference matters. Presume that you are concerned with improving human lives. One way to do that is to expand the availability of education. More people reach higher levels of education today than did in 1930–and more people lead safer, longer, lives. This strategy won’t produce equity, however. As educational attainment has risen in the United States, the most educated people have increased the wage gap.

Another way to enhance human welfare is to yield outputs that benefit everyone: skillful doctors and engineers who have great new technologies, medicines, training, etc. To get the best results, it might be smart to concentrate resources at very high-status institutions. The universities that produce the most scientific advances tend to be highly competitive institutions in inequitable systems like the US.

Presume that you want to promote mobility. Then you must reduce the correlation between parents’ and children’s educational attainment. That means admitting and advancing more students whose parents were disadvantaged. It also means, by definition, admitting fewer students from advantaged homes. Increasing the number of total slots is an inefficient way to enhance mobility. Mobility requires competitiveness: when people can compete better, newcomers can more easily knock off incumbents. When individuals are protected against failure, mobility is hampered.

Mobility also operates at the level of communities. In a system of Schumpeterian “creative destruction,” Detroit can fall while Phoenix rises. European countries intervene much more effectively than we do to protect their deindustrializing cities. That is better for human flourishing, but it may also hamper mobility.

Finally, presume that you really want to improve equity. One way to do that would be to improve the education of the least advantaged while holding the top constant. Another way would be to lower the quality and value of the education received by the top tier. Very few people would support doing that, even if it improved equity. That’s because most people think that welfare and mobility are at least as important as equity. (I leave aside liberty, although that is also a valid and important principle.)

Hybrid goals are possible. Perhaps what we want is to maximize the welfare of the least advantaged while not allowing inequality to get out of hand or mobility to vanish. That’s arguably the outcome in Denmark and Sweden. The US may under-perform regardless of how you weigh the three goals. We have vast inequality, limited mobility, and not much safety or health for a large swath of our people. But even if we can make progress on all three fronts at once, they are still different directions.

See also: to what extent can colleges promote upward mobility?, when social advantage persists for millennia, and the Nordic model

Generation Justice wins the Everyday Democracy Paul and Joyce Aicher Leadership in Democracy Award

- Facebook896

- Total 896

(Hartford, CT) I’m in Hartford for a board meeting of the Paul J. Aicher Foundation, whose project is Everyday Democracy. This is a good moment to highlight the first Paul and Joyce Aicher Leadership in Democracy Award, which Everyday Democracy awarded to a New Mexico nonprofit, Generation Justice.

Great civic engagement. Building media literacy skills in youth, with a racial equity lens. Applying journalistic integrity to its advocacy and racial equity work. These are all reasons that Generation Justice, a New Mexico non-profit established in 2005, was selected as the winner.

Please check out the powerful media of Generation Justice, here.

why study social justice?

- Facebook135

- Total 135

I just finished teaching a philosophy course in which the primary question was “How should I live?” We spent some time reading and thinking about personal and internal questions, such as what constitutes happiness and truthfulness and whether those are possible and desirable states. We also talked about political justice, reading a fairly standard canon of Mill, Rawls, Nozick, and Scanlon, plus Bayard Rustin, Kwasi Wiredu, Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze, Steve Biko, Audre Lorde, and Susan Bickford. The premise of those readings was that it might be important to know what justice is when choosing how to live a good life.

Meanwhile, my students were introspecting about the principles that guide their lives and how those principles are organized into networks of moral ideas.

The students, as they recognize, emphasize attitudes toward concrete other people in their lives plus values related to learning: empathy, openness, and hard work. The kinds of ideals that figure in political theory–liberty, equality, welfare, and democracy–are mostly absent or marginal from their maps of their own animating ideals.

They offered several explanations for this gap between what I’d assigned and what they perceived when they looked inward. Some thought it was evidence of their own privilege: they don’t have to think about freedom because they take it for granted. (For the same reason, they don’t list “having enough to eat” as a guiding principle.) Others thought their introspective maps were developmentally appropriate: their job right now is to learn and revise their views, not to hold onto principles. Some were skeptical about the validity of any abstract principles of justice. And some thought that their own views reflected political discouragement or disenfranchisement at a hard time in our history. They don’t strive directly for democracy because they don’t believe that they can.

The question arises, Why should we study and conduct research on justice? Why should justice be part of any curriculum, and specifically a curriculum whose leading question is about the good life for the individual students?

I think my colleagues in academia (writ large) would divide on that question.

For some academics, justice seems irrelevant to their professional work or is a mere matter of opinion. “Who decides what’s good or bad?” is a frequent question. It suggests that we scholars and students shouldn’t try to define justice and defend our stances in academic contexts, publications and classrooms. The most we should do is to study and explain why various populations define justice in various ways.

For some academics, commitment to justice is measured by the degree of one’s distaste for the prevailing political and economic system. The way to assess whether a colleague is oriented to justice is to see how strongly she or he opposes the status quo. One way to demonstrate such opposition is to study various concrete forms of injustice. Thus justice-oriented scholars are those who investigate and teach situations that should be abhorred.

By this standard, my curriculum would be deficient, since we did not go deeply into the empirical facts about poverty, racism, or tyranny. Moreover, we read authors chosen for their divergent views. By the time you see that Hayek and Nozick would like less government than we have, and Rawls and Scanlon would like more, you could perhaps conclude that we have about the right amount of government. I’m not saying that splitting the difference would be valid logic, but the question is whether ideological diversity might have the psychological effect of making students confused or complacent.

I belong to a third category of academics, for whom being seriously concerned with justice means asking what it is and what we can do to promote it. Both parts of that question are topics for research. One can study what justice is by critically investigating the available theories and their relationship to concrete facts. One can also study strategies and tactics for promoting justice. Those two topics intersect, because a goal without any plausible strategy is not much of a goal; and a strategy without a defensible account of its purpose is not worth undertaking. I criticize what’s called “ideal theory” in political philosophy because its focus on end states–without serious consideration of strategy–yields misleading results.

Speaking of privilege, I am privileged to move across communities with quite different ideological centers. One day recently, I was at a conference where libertarian economists were well represented and may have predominated. A speaker showed a photo of FDR and said something like, “Since we’re all classical liberals, I can count on you to hate this guy.” I suspect the speaker overestimated the ideological uniformity of his audience; I may have had some company in deeply admiring Franklin D. Roosevelt. But it was certainly a different context from the Tufts classroom where, on the very next day, we discussed this fascinating exchange between Hillary Clinton and Black Lives Matter activist Julius Jones about how to diagnose and address racial injustice in America. The center of gravity in that room lay somewhere between Clinton and Jones, with only one student openly asking whether the assumption that those two people share–that America is deeply racist–is a given.

The disadvantage of posing the question “what is justice?” in a truly open way is that one can discourage action. For instance, I think that the pending tax bill is awful, but I also have questions about some arguments against it. There’s a strong equity-based argument for curtailing the charitable tax deduction, and there’s even a case that the Republicans have generated new federal revenues while passing a deeply unpopular tax cut for the upper stratum, which is likely to be repealed. The net result, as early as 2019, may be a larger stream of revenue than would have had been possible without this bill. But making such critical points (if anyone paid attention) could dampen enthusiasm for the opposition, and there’s a plausible case that the tax bill is on its way to passage because of relatively weak popular opposition. I wouldn’t want to undermine anyone’s motivation to protest by posing awkward questions.

The advantage, of course, is learning. I feel challenged and enriched by the conference at which libertarians were well represented. I think I understand better the relative advantages and disadvantages of three ways of understanding what works in the real world: talking with people, conducting scientific research on impact, and observing price signals. The last category is valuable for reasons that you won’t notice if you hang around all the time with lefties.

In the end, we need both commitment and critical analysis, both true openness to alternative views and effective, coordinated action. We need utopian vistas and hard-nosed tactics. The balance is very hard, but there must be at least a place for abstract and dispassionate inquiry into the nature of justice.

[See also: social justice should not be a cliché; we are for social justice, but what is it?; a method of mapping moral commitments as networks.]

youth in the Alabama Senate race

- Facebook50

- Total 50

CIRCLE estimates that 23% of young Alabamians voted in yesterday’s special election. Just for a rough turnout comparison, 21.5% of youth in the United States as a whole voted in the 2014 election. We would normally expect turnout to be lower in a special election with only one person on the ballot than in a national Congressional election, and also lower among Alabama youth than youth across the country because just 40% of young Alabamians have any college experience (and college is correlated with voting). Thus I would call the turnout pretty good compared to expectations.

According to the Exit Polls, youth supported Doug Jones over Roy Moore by 60% to 38%. The older vote was dramatically different, with Moore winning people over 45 pretty easily. CIRCLE suggests two interesting contributing factors. First, young Alabamians are more diverse. “More than a third of the state’s young people are Black, and … Black voters of all ages went overwhelmingly for Jones (96%) in yesterday’s race.” Second, Moore may not have “garner[ed] overwhelming support even among youth who identify as conservative or Republican.” CIRCLE has previously found that “some Republican-leaning youth break with older voters on same-sex marriage and other social issues that were central to Moore’s campaign in Alabama. In addition, CIRCLE analysis of the Pew Research Center’s Political Typology dataset finds that only 5% of young people who lean toward or belong to the Republican party are “Steadfast Conservatives” (compared to 25% of Republicans or Republican-leaners aged 30+) while 31% are “Young Outsiders” who may feel less committed to the party and its candidates.”

More detail is on the CIRCLE website.