- Facebook154

- Total 154

Articles entitled “The Secret X,” are usually exposés of X’s secret crimes and shames. But Edward Mendelson’s article “The Secret Auden” (New York Review, March 20) catalogs the many discreet acts of kindness, sensitivity, and self-sacrifice of W.H Auden. Auden sounds like one of the nicest famous people who ever lived–sleeping outside the door of an old woman’s apartment to help her with night terrors, befriending awkward teenagers at literary parties, helping convicts with their poetry.

What does this have to do with the man’s writing? Auden went on a long inward moral journey. After his early celebrity as a left-wing poet, he was suspicious of his own motives and the causes they had attached him to. His relentless self-criticism was not barren, self-destructive, or cynical; it gave him material for his best writing.

Mendelson offers an example. Isaiah Berlin was “Auden’s lifelong friend,” and on the surface it would appear that the two men held similar views: resistant to ideology and tolerant of human beings in all their crooked particularity. In his essay on Turgenev, Berlin wrote: “The dilemma of morally sensitive, honest, and intellectually responsible men at a time of acute polarization of opinion has, since [Turgenev’s] time, grown acute and world-wide.” Mendelson summarizes Auden’s response:

Whatever Berlin intended, a sentence like this encourages readers to count themselves among the sensitive, honest, and responsible, with the inevitable effect of blinding themselves to their own insensitivities, dishonesties, and irresponsibilities, and to the evils committed by a group, party, or nation that they support. Their “dilemma” is softened by the comforting thought of their merits.

This is an example of how far Auden’s journey had taken him: from ideology to the anti-ideological liberalism of Isaiah Berlin, and then beyond that to a stance of deep self-criticism in which even anti-ideology is an ideology. As Mendelson notes, Auden dedicated “The Lakes” (1952) to Berlin. This poem is about preferring homely lakes to the great ocean, and enjoying their diversity and particularity. Berlin might agree, but Auden inserts a warning (not quoted here by Mendelson): “Liking one’s Nature, as lake-lovers do, benign / Goes with a wish for savage dogs and man-traps.”

At a high-theoretical level, Auden explored the many ways in which we are tempted to adopt self-aggrandizing ideas. In his poems, Auden depicted those clashing ideas with irony and humor. And in his private life, he tried to act kindly and lovingly toward all. It seems he actually lived the life he (over-generously) attributed to Sigmund Freud:

Of course they called on God, but he went his way

down among the lost people like Dante, down

to the stinking fosse where the injured

lead the ugly life of the rejected,and showed us what evil is, not, as we thought,

deeds that must be punished, but our lack of faith,

our dishonest mood of denial,

the concupiscence of the oppressor.

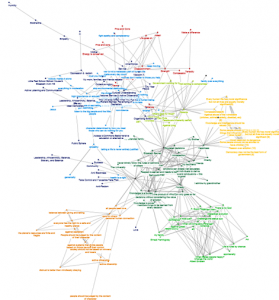

(See also: In “Defense of Isaiah Berlin,” Six Types of Freedom,” “The Generational Politics of Turgenev,” “mapping a moral network: Auden in 1939,” “notes on Auden’s September 1, 1939,” “on the moral dangers of cliché,” and “morality in psychotherapy.”)