- Facebook736

- Total 736

I have been suggesting that people map their own moral opinions as networks and critically examine the shapes that result. My students are doing that (because they have to), and some friends are doing it voluntarily. See my students’ collective map as an illustration.

One way in which networks vary is in their degree of centralization. If you map all your moral commitments and the links among them, you may reveal a network that centers around a single idea, or a very flat network in which no idea has more links than any other–or something in between. I personally favor flatter networks (for abstract philosophical reasons), but I don’t believe my reasons are decisive. So instead, I would pose these questions:

If you have a very flat network, in which no idea is appreciably more important than any other, is that a mistake? Should any of your existing commitments be made more central, because they are particularly important? What would happen, hypothetically, if you added to your network a new general and demanding principle that would link to many other ideas? (For instance: “Always maximize the well-being of all sentient creatures.”) Look at the resulting network and consider whether it has any pull on you.

If you have a highly centralized network, ask yourself whether the ideas that have proven so important deserve their weight. Are you certain that they are valid? Are you sure they are more important than your other commitments? What would happen if, for some reason, you ceased to believe in these central nodes–would the whole network fall apart? And are you able to reason with another person who does not happen to share your central commitments? Could you avoid your central beliefs in order to make arguments that the other person could accept and still navigate through your own network?

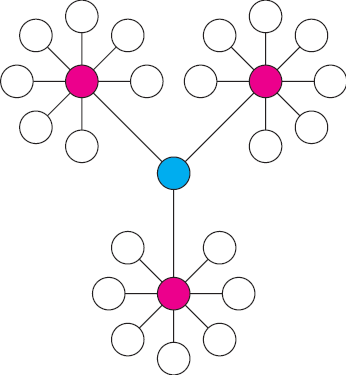

Now for a little more technical detail. There are actually several ways in which a node can be central in a network. In the image below, the red nodes are the most central in the sense that they have the most direct links to other nodes (7 each). A better way to say that is that each red node has 7 out of the total 24 links on the map, or 29%.

However, the blue node is central in a different sense: it lies on the path between the greatest number of other nodes. To get from any node in one cluster to any node in a different cluster, you have to go through the blue node. Yet the blue node only has 3 direct links (12.5%).

It is worth checking your own moral network for both kinds of centrality because they both matter.

Consider a person who believes in God. Presumably, God should be linked to a lot of other moral ideas–to all of them, at least indirectly. Some believers would aim for a spoke-and-wheel network in which God directly touched every other idea. To drop the network metaphor for a moment, they would immediately invoke God as the reason for every moral belief. “Purity of heart is to will one thing.”

But I do not believe that such a network design is characteristic of pious people in any religious tradition. Typically, faith takes the form of a whole set of linked ideas, some abstract and general and others very concrete. The ideas may include the stories and characters in scripture, the metaphysical attributes of God, the community of believers and their institutions, and the traditions of the faith (see my typology). Monotheists struggle to maintain one reasonably coherent network in which God is very important, but they do not organize their whole network as a single spoke-and-wheel.

Thus, for a monotheistic believer, God could appear as either the blue node or as one of the red nodes in the figure above.

In the blue-node scenario, God is what links everything together. Sooner or later, when discussing moral issues, this person would invoke God as a fundamental reason. Yet God would not be directly and immediately pertinent to most everyday decisions. The person might decide what to buy, how to vote, and how to raise her kids without immediately citing God. The connection to God goes through other ideas, such as “Do unto others as you would have them to do you,” or “Be a good member of the community.”

In the red-node scenario, God is immediately relevant in one domain of life: presumably, the religious domain. When deciding how to worship, what dietary rules to follow, etc., God comes immediately to mind. God is also linked indirectly to the whole network. But God is rather far removed from some domains of life, which might include the economy and politics.

I am using monotheistic faith as an example here, because everyone is familiar with what it means. But we could replace God with a strongly secular principle, such as “science offers the only truth.” In that case, too, the principle might be placed as the blue node, as the red node, or as one of the white nodes.

Overall, the network shown above is fragile because it only holds together thanks to the one blue node. Knock that out and there is no network at all. If the central node is true and deeply significant, then so be it. Deep faith (whether religious or otherwise) means committing to an idea even at the risk of having a fragile network. But if one believes that it is important to deliberate with other people, then the network shown above is problematic because the conversation will break down as soon as your interlocutor denies the contents of the blue node. You will have no other way to make your point than to repeat that node.

I fundamentally believe in deliberation because of human cognitive and motivational limitations. Each of us has a narrow and biased worldview, and the best we can do is to interact with others. That means that if your network is as centralized as the one shown above, you are at risk. On the other hand, if your network is completely flat, maybe you lack a sense of what is most important.