- Facebook272

- Total 272

There’s lots of conversation right now about Donald Trump’s mental condition. It includes claims that he demonstrates narcissistic personality disorder and that changes in his speech patterns reveal cognitive decline. I [analyzed] his speech pattern from a particular angle here.

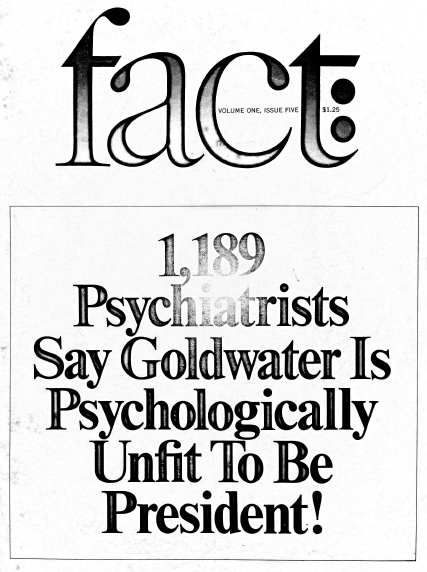

This discussion evokes the episode in 1964, when Fact magazine surveyed psychiatrists about then-candidate Barry Goldwater’s psychological fitness to be president.

Just under half (49.2%) of the 2,417 respondents thought he was unfit, with the rest split evenly between those who didn’t believe they could answer and those who considered him fit for office. Fact also gave respondents a chance to write comments and printed 40 pages of quotes from their answers. Goldwater sued and won over $1 million in damages (which bankrupted Fact magazine), leading to the American Psychiatric Association’s “Goldwater Rule,” which forbids members from making evaluative comments about public figures whom they have not examined as individual patients. A patient/physician relationship triggers ethical responsibilities that are absent when psychiatrists discuss public officials.

For me, the original Fact magazine issue is a fascinating example of professional authority encountering politics. It’s important to note that a considerable minority of the quoted statements either object to psychoanalyzing Goldwater without examining him in person or vouch for his mental health. Some of the surveyed psychiatrists even opine that he is the only sane candidate, surrounded by crazy socialists. But the majority of the quoted MDs make claims that now seem risibly dated and morally problematic. They do so under their professional titles, in a magazine entitled “Fact.” For example:

- “Descriptions of his early life that I have read indicate to me that his mother assumed the masculine role in his family background. … The picture, therefore, is of a domineering, emasculating mother and a somewhat withdrawn, passive, narcissistic father. … This would provide a fertile background for sado-masochistic temperament, such as is seen in paranoid states.” — M.D., name withheld.

- “From TV experiences, it is apparent that Goldwater hates and fears his wife. At the convention, she consistently appeared depressed and withdrawn. Certainly she was not like the typical enthusiastic candidate’s wife, e.g., Mary Scranton.” — M.D., name withheld.

- “Barry Goldwater’s mental instability stems from the fact that his father was a Jew while his mother was a Protestant. This ethnic and cultural split accounts for his feelings of insecurity and spiritual loneliness. … ” — M.D., name withheld.

- “In trying to analyze Mr. Goldwater’s behavior I am tempted to call him a ‘frustrated Jew.’ … He has never forgiven his father for being a Jew. … What the Senator from Arizona stands for is the antithesis of the traditional Jewish concepts of social justice, of humility, of moderation in speech and action, and of concern for the feelings of others, especially the vanquished. In eschewing these concepts, the Senator subconsciously expresses his hatred for his Jewish father.” — Max Dahl, M.D. Supervising Psychiatrist [etc.]

- “In allowing you to quote me, which I do, I rely on the protection of Goldwater’s defeat at the polls in November; for if Goldwater wins the Presidency, both you and I will be among the first into the concentration camps.” – G. Templeton, M.D., Director, Community Hospital Mental Health [etc.]

- “Characterologically, Goldwater is like many middle-class Americans. He is ‘formula’ oriented with a belief in the infallibility of his own rhetoric. … In short: Goldwater is an anal character who believes all’s well in his ‘tidy’ world.” — M.D., name withheld.

- “From his published statements I get the impression that Goldwater is basically a paranoid schizophrenic who decompensates from time to time.” — M.D., name withheld.

I think we should talk about Donald J. Trump’s character and psychological fitness for office. It seems problematic to use the Goldwater Rule to keep the whole psychiatric profession out of this discussion. And yet these quotes from 1964 remind us how historically-relative, value-laden, and agenda-driven people can be, even when they present themselves as scientific specialists dealing only in Facts.