- Facebook602

- Total 602

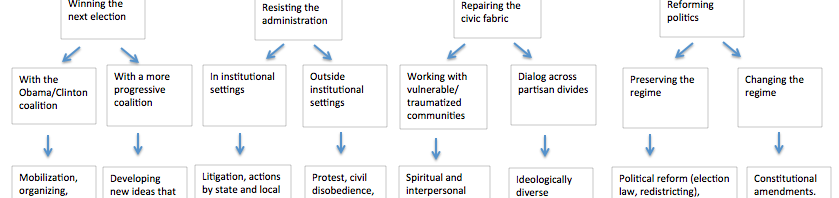

To respond to Trump’s election, we must address who is organized, and how.

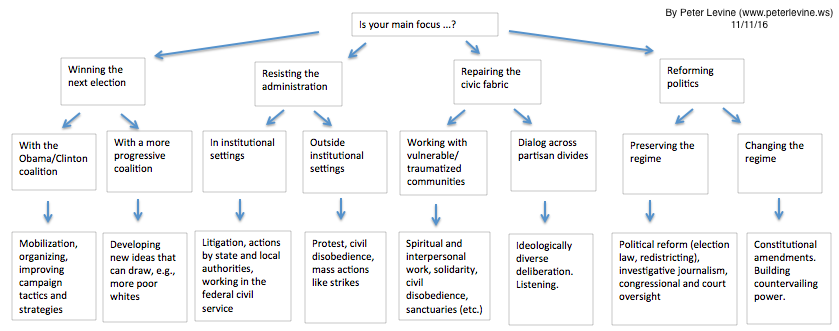

Members of organizations are more likely to vote and to take the more costly actions that will be vital during the Trump years, such as protest and resistance. As a quick-and-dirty illustration, consider the correlation between the number of groups that people belong to and the proportion who say they vote.*

This graph combines all kinds of groups. When people belong to organizations that offer them voice and accountability, that address social or political issues, and that encompass at least some diversity, they are not only more likely to vote; they are also more likely to act and choose responsibly. Members of such groups learn to negotiate, to set appropriate expectations for their leaders, and to feel ownership for results.

Before the election, I proposed that Trump mainly appealed to people who lacked accountable organizations, and that’s one reason that they opted for a totally irresponsible (as well as a cruel) celebrity candidate. They behaved as alienated spectators rather than as political agents. I also expected turnout to be relatively weak among people leaning toward Trump.

Theda Skocpol finds that the rural and exurban areas where Trump performed best did have “organized networks – NRA, Christian Right, some RNC and Koch network/AFP presence – that amplified the right media attacks on HRC nonstop and persuaded many non-college women and some college women in those areas to go for Trump because of the Supreme Court.” Skocpol acknowledges that Trump himself “had no organization,” but, she says, he “made deals to get the NRA, Christian right and GOP federated operations on his side. They have real, extensive reach into nonmetro areas.” I’ve also estimated, based on Exit Poll data, that 56% of Trump voters attend church at least monthly. His turnout wasn’t great, but it was sufficient to win the Electoral College.

I was wrong in part. Trump did well because of the traditional mechanism: outreach by groups. However, I would still propose that the groups that reached Trump voters were unaccountable to them. The Koch Network, for instance, is centralized, fueled by two brothers’ money, and undemocratic and opaque in its internal organization. The relationship between such an organization and its target population is transactional and instrumental: it spends money to persuade them to vote. That is consistent with my view that Trump’s voters aren’t authentically organized. Being mobilized is not the same thing.

Meanwhile, Skocpol is definitely right about the other side:

HRC had the typical well-funded presidential-moment machine, an excellent one. We on the center left seem to treat these presidential machines as organization[s], and they are, but they are not as effective as longstanding natural organized networks. … [Off] the coasts, Democrats no longer have such reach beyond what a presidential campaign does on its own. Public sector and private sector unions have been decimated. And most of the rest of the Democratic-aligned infrastructure is metro based and focused. That infrastructure is also fragmented into hundreds of little issue and identity organizations run by professionals. HRC’s narrow loss was grounded in this absent non-metro infrastructure – and Dem Party losses in elections overall even more so.

In areas where progressive voters predominate, we need a much more authentic, democratic, and integrated base of organizations. Instead of parachuting presidential machines into diverse urban areas every four years in search of votes, the left must invest in younger and more diverse local leaders who have real authority and voice and who can work continuously. American democracy has always functioned best when organizations offer a range of goods, of which political power is just one. For instance, churches offer spirituality; unions raise salaries. Their members ultimately vote, but that’s not the main service these organizations advertise. Right now, resources should flow to multipurpose organizations and movements that will turn out voters in 2018 and 2012, but that will do much before then–starting with protecting safety and civil rights against both hateful individuals and government agencies.

The decline in votes in Wayne County (Detroit) between 2012 and 2016 (37,364) will almost certainly be larger than the final margin of victory for Michigan. Milwaukee saw a 41,000-vote decline that was bigger than the state’s margin. I suspect that scarce investment in organizing was as important in Wisconsin as voter-suppression. These statistics should ring loud alarms, if they haven’t already. How many young African American and Arab American organizers can count on paid activist jobs in Detroit in 2017 and 2018?

Meanwhile, we also need organizations in red states and red counties, in rural areas and exurbs. The point of organizing there is not to show empathy to Trump voters or to honor their concerns. The point is to win. Particularly in 2018, anti-Trump votes will be very poorly distributed–far too concentrated in the great cities to win the House and Senate back. Every extra vote in a white non-urban county will matter, and that requires organizations to change minds, to empower the disenfranchised, and to offer real benefits. By the way, although I think the Democratic Party is a necessary component of the opposition, it is not sufficient. Electing or reelecting responsible and caring Republicans in red districts is also essential.

In our October poll of Millennials, we found that just 30% of Clinton supporters had been contacted by a campaign or organization that had urged them to vote; 28% of young Trump supporters had been contacted; and 70% had not been contacted at all. Young people who had received multiple contacts were 19 points more likely to say they’d vote than those who’d received none. That poll was a warning that young Americans across the spectrum were not being reached by organizations. Young Trump voters were almost as likely to receive outreach as Clinton voters were: another indictment of the left’s investments. The time to change this is now.

*I’m showing General Social Survey data from 1987 about whether people “always vote” and from 2000 about whether they voted in the last presidential election. Unfortunately, I can’t find more recent comparable data, but I hope the graph illustrates an important pattern. Note that the correlation applies to people who have no college experience (the working class) as well as the population as a whole.