- Facebook84

- Threads

- Bluesky

- Total 84

In linguistics, a language is a whole system of communication used by a group, encompassing its semantics, grammar, and pragmatics. A dialect is a particular form of a language typical of a specific region. A sociolect is like a dialect, except that it is used by a dispersed social group, such as a profession or a class. A register is a form of a language used in a particular situation or context, such as by lawyers in court. And an idiolect is the distinctive way that an individual speaks: that person’s active vocabulary, grammar, accent, and preferred forms and style of speech.

Previous authors have used these distinctions from linguistics to inform models of culture. Language offers a useful model or example for understanding culture because we are familiar with explicit efforts to learn second languages, to list components of a given language in a dictionary, and to invent a writing system to represent a language (Goodenough 1981, p. 3; Goodenough 2003). I am especially interested in the aspects of culture that involve value-judgments: ethics, politics, aesthetics and religion.

I believe the following ten points from linguistics are relevant to thinking about culture (in general) and specifically about values:

- Registers, dialects, sociolects, and languages all encompass variation. Each person talks and understands differently from others and evolves as a speaker over time. Therefore, the same body of communication by real human beings can be carved up in many ways. For instance, we can draw a dialect map of the USA that shows more or fewer regions, and we can declare the same material to be a language or a dialect depending on whether we prefer to accentuate differences or similarities.

- Idiolects do not nest neatly inside dialects and sociolects, which do not not nest neatly inside languages. They are more like complex Venn diagrams. An individual may draw on several dialects or languages. In cases of code-switching, the individual sometimes uses one register or sociolect and sometimes switches to a different one. Or people may consistently use a mix of influences from multiple sources. For instance, Spanglish is characterized by Spanish influences on English–and there are several different regional Spanglish dialects within the United States today. On the other hand, imagine an elderly American whose speech reflects some influence of Yiddish from the old country. Her idiolect is then not part of any dialect but is a unique mix of two languages with which she may successfully communicate even though no one else nearby sounds like her.

- Nobody knows all of any given language, dialect, or sociolect. An effort to catalogue an entire language describes a body of material that none of the users know in full. For instance, nobody knows all the meanings of all the words in an impressive dictionary (which is, itself, an incomplete catalogue of the entire language). Instead, people share sufficient, overlapping portions of the whole that they can communicate, to varying degrees.

- Each of us knows our own entire idiolect. (That is what the word means.) However, we could not fully describe it. For instance, I would not be able to sit down and list all the words I know and all the definitions I employ of those words, let alone the grammatical rules I employ. If I were presented with a dictionary and asked which words I already know, I would check too many of them. The dictionary would prompt me to recall words and meanings that are normally buried too deep in my memory for me to use them. That brings up the next point:

- Language is dynamic, constantly changing as a result of interaction. A language constantly borrows from other languages. A person’s idiolect is subject to change depending on whom the person talks to. The best way to characterize an idiolect or a language (or anything in between) is to collect a corpus of material and investigate its vocabulary and grammar. That is a worthwhile empirical exercise, but it requires a caveat. The corpus is a sample taken within a specific timeframe. The idiolect or the language will change.

- It is possible to make a language (or a smaller unit, like a sociolect) relatively consistent among individuals and sharply distinguish it from other languages. For instance, a government can set rules for one national language and encourage or even compel compliance through schooling, media, religious observance, and even criminal penalties. Law schools teach students to talk like lawyers in court. However, there are also language continua, in which local people speak alike, people a little further away speak a little differently, and so on until they become mutually unintelligible. Before the rise of the nation-state and modern mass media, language continua were much more common than sharply distinguishable languages. Linguistic boundaries require exercises of power that are costly and never fully successful. Meanwhile, at the level of an idiolect, individuals may strive to make their own speech consistent and distinctive or else let it change dynamically in relation with others. People vary in this respect.

- Language is–in some way or degree–holistic. That is to say, the components of a language depend on other components. For instance, a definition of a word uses other words that need definitions. I leave aside interesting and complicated debates about holism in the philosophy of language and presume that some degree of holism is inescapable.

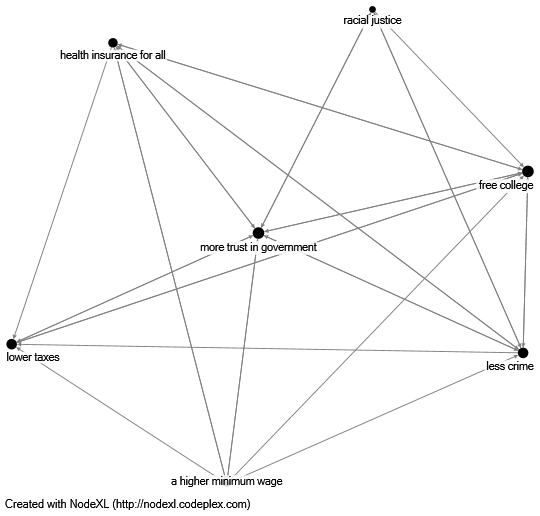

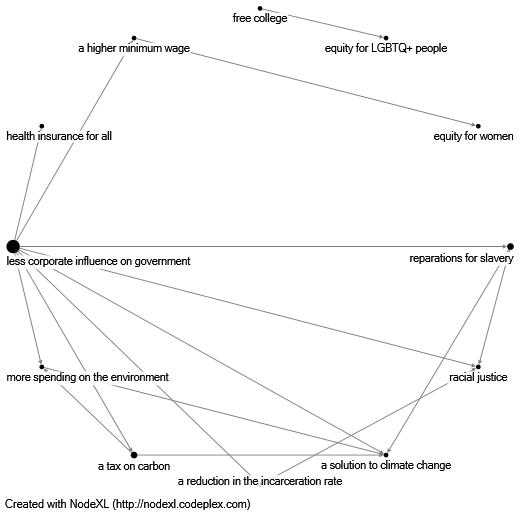

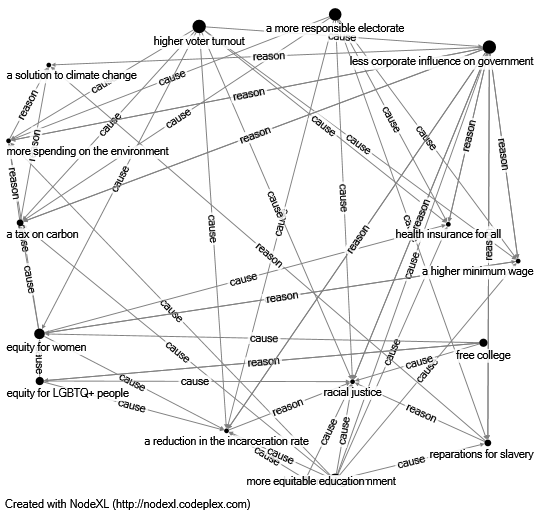

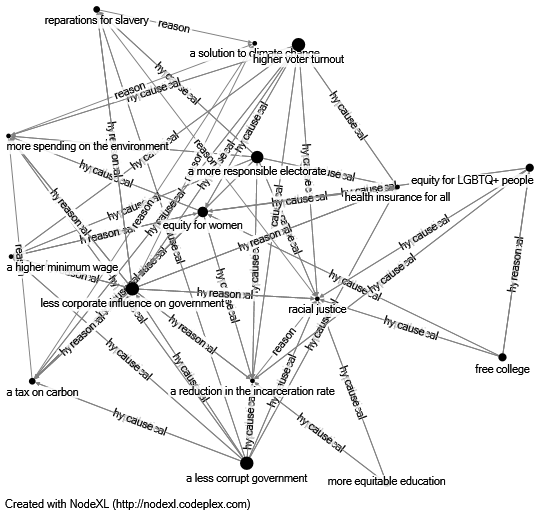

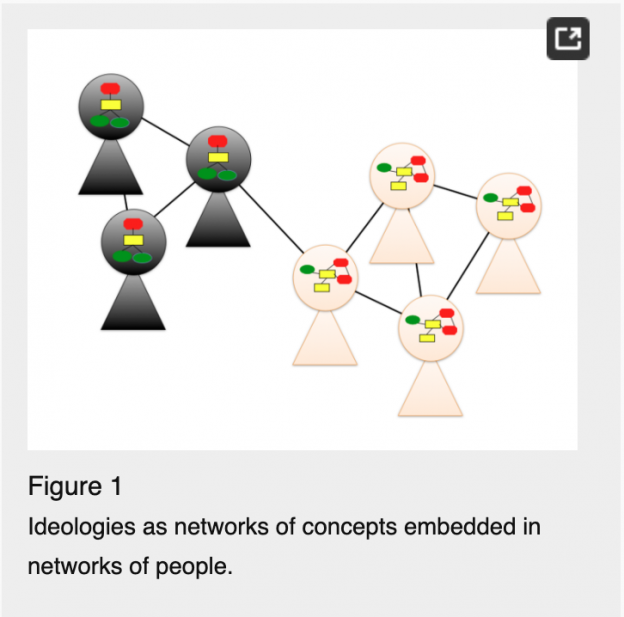

- Therefore, it can be helpful to diagram an idiolect, a dialect, or a language as a network of connected components rather than a mere list. I am not saying that language is a network; language is language. However, semantic network diagrams are useful models of idiolects, dialects, and languages because they identify important components (e.g., words) and connections among them. A semantic network diagram for a group of people will capture only a small proportion of each individual’s language but may illuminate what they share, showing how they communicate effectively.

- While words and other components of language are linked in ways that can be modeled as networks, people also belong to social networks, linked together by relationships of influence. A celebrity influences many others because many people receive her communications. The celebrity is the hub of a large social network. At the opposite extreme, a hermit would not influence, or be influenced by, anyone (except perhaps by way of memories).

- Whole populations change their languages surprisingly quickly, and sometimes without mass physical migration. The same population that spoke a Celtic language (Common Brittonic), transitioned partly to Latin, then fully to Germanic Anglo-Saxon, and then to a mixture of Anglo-Saxon and French without very many people ever moving across the sea to England. Today about 33 million people in South Asia also speak dialects of it. A few people can strongly influence a whole population due to their network position–which, in turn, often reflects power.

The point of this list is to suggest some similarities with other aspects of culture. Like a language, another part of a culture can be modeled as a shared network of components (e.g., beliefs, values, or practices) as they are used by people who are organized in social networks, which reflect power.

Such a model is a radical simplification, because each individual holds a distinctive and evolving set of components and connections (e.g., linked moral values); but simplifications are useful. And we can model culture usefully at multiple levels, from the individual to a vast nation.

There are precedents for this kind of analysis. The anthropologist Ward Hunt Goodenough encountered the concept of idiolects in the 1940s, while studying for a doctorate in anthropology (Goodenough 2003). By 1962, he had postulated the idea of “each individual’s private culture, if we may call it that, [which] includes his conception of several wholly or partially distinct cultures (some well elaborated and others only crudely developed in his mind) which he attributes to others individually and collectively, both within and without his community. A person’s private culture is likely to include knowledge of more than one language, more than one system of etiquette, more than one set of beliefs, more than one hierarchy of choices, and more than one set of principles for getting things done” (Goodenough, 1963, 261)

Later, Goodenough named a private culture a “propriospect” from the Latin words for “private” and “view” (Goodenough 1981, p. 98). Harry Wolcott summarizes: “Propriospects … are networks of sense-making connections created and constantly being reformulated by each of us out of direct experience. As we develop and refine our competencies, simultaneously we ‘construct” (and continually ‘re-model’) our individual propriospects” (Wolcott 1991, p. 267).

Individuals may actually share fundamental characteristics of a group, they may perceive themselves to share those characteristics, and they may be viewed by others as sharing them–but these perceptions do not necessarily align, because every group encompasses diverse propriospects. For instance, you might think that believing in God is essential to a culture; and since you believe in God, you are part of that culture; but someone else may define the culture differently and view you as an outsider.

In a review of Goodenough, Mac Marshall (1982) wrote, “While some may disagree with the finer points of his argument, his position on these matters represents the dominant orientation in American anthropology today.”

A different precedent derives from the Polish tradition of humanistic sociology, founded by Florian Znaniecki in the early 1900s. In the 1980s, a Polish sociologist named Marek Ziolkowski (later a distinguished diplomat) wrote interestingly about “idio-epistemes” (presumably from the Greek words for “private” and “knowledge”) meaning “not only … the cognitive content of an individual’s consciousness at a given moment, but … the whole potential content that can be activated by the individual at any moment, used for definite action, and reproduced introspectively.”

Ziolkowski called on sociologists to “enquire into the social regularities in the formation of idio-epistemes, seek relationships among them, establish basic intragroup similarities an intergroup differences.” He acknowledge that any individual will have a unique mentality, “yet every individual shares an overwhelming majority of opinions and items of information with other definite individuals and/or groups.” Those similarities arise because of shared environments and deliberate mutual influence. Ziolkowski coined the word “socio-episteme” for those aspects of an idio-episteme that are shared with other individuals. As he noted, these distinctions were inspired by concepts from linguistics.

Even earlier, in 1951, the psychologist Saul Rosenzweig had coined the word “idioverse” for an individual’s universe of events” (Rosenzweig 1951, p. 301).

An analogous move is Wilfred Cantwell Smith’s influential redefinition of “religion” from a bounded system of beliefs (each of which contradicts all other religions in some key respects) to a “cumulative tradition” of thought and behavior that varies internally and overlaps with other traditions (Smith 1962). According to this model, everyone has a unique religion, although shared traditions are important.

These coinages–idioverse, propriospect, idio-episteme, and cumulative tradition–capture ideas that I would endorse, and they reflect research, respectively, in psychology, anthropology, sociology, and religious studies. However, none of the vocabulary has really caught on. There may still be room for a new entrant, and I would like to emphasize the network structure of culture more than the previous words have done. Thus I tentatively suggest idiodictuon, from the classical Greek words for “private” and “net” (as in a fishing net–but modern Greek uses a derivation to mean a network). An individual has an idiodictuon, a group has a phylodictuon, and a whole people shares a demodictuon.

These words are unlikely to stick any better than their predecessors, but if they did, it would reflect their diffusion through a social network plus their utility when added to people’s existing networks of ideas. That is how all ideas propagate, or so I would argue.

A final point: “culture” encompasses an enormous range of components, including words, values, beliefs, habits, desires, and many more. Given this range, it is useful to carve out narrower domains for study. Language is one. I am especially interested in the domain of values, so I would focus on the interconnections among the values that people hold.

Note, however, that there is no neat way to distinguish values from other aspects of culture, such as desires and urges or beliefs about nature. In his influential empirical theory of moral psychology, Jonathan Haidt identifies at least five “Moral Foundations,” one of which is “sanctity/degradation.” I would have treated this category as a powerful human motivation, akin to sexual desire or violence, but not as a moral category, parallel to “care/harm.” Maybe Haidt is right, or maybe I am, but the evidence isn’t empirical. People actually see all kinds of things as the basis for action and make all kinds of connections among the things they believe. They may link a moral judgment to a metaphysical belief, or a personal aversion, or an aspect of their identity, or a belief about prevailing norms. When we carve out an area for study and call it something like “morality” or “ethics” (or “religion,” or “politics”) we are making our own claims about how that domain should be defined. Such claims require philosophical arguments, not data.

So the steps are: (1) define a domain, a priori, (2) collect a corpus of material relevant to that domain, (3) map it as a network of ideas, and (4) map the human relationships among people who hold different idiodictuons.

For me, the ultimate point is to try to have better values, and the study of what people actually value is preparatory for that inquiry. Clifford Geertz concludes his famous “Thick Description” essay: “To look at the symbolic dimensions of social action–art, religion, ideology, science, law, morality, common sense–is not to turn away from the existential dilemmas of life for some empyrean realm of de-emotionalized forms; it is to plunge into the midst of them. The essential vocation of interpretive anthropology is not to answer our deepest questions, but to make available to us answers that others, guarding other sheep in other valleys, have given, and thus to include them in the consultable record of what man has said.”

References:

- Geertz, Clifford, “Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture.” In Geertz, The interpretation of cultures. Basic books, 1973. (pp. 41-51).

- Goodenough, Ward, Cooperation in change : an anthropological approach to community development. New York, Russel Sage 1963

- Goodenough, Ward H. In Pursuit of Culture, Annual Review of Anthropology 2003 32:1, 1-12

- Goodenough, Ward H. Culture, Language and Society (Menlo Park: Benjamin Cummings, 1981)

- Mashall, Mac, “Culture, Language, and Society by Ward H. Goodenough” (review), American Anthropologist, 84: 936-937.

- Rosenzweig, Saul. “Idiodynamics in Personality Theory with Special Reference to Projective Methods 1.” Dialectica 5, no. 3-4 (1951): 293-311.

- Smith, William Cantwell, The Meaning and End of Religion (1962), Fortress Press Edition, Minneapolis, 1991

- Wolcott, Harry F. “Propriospect and the acquisition of culture.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly 22, no. 3 (1991): 251-273.

- Ziolkowski, Marek, “How to Make the Sociology of Knowledge Sociological?.” The Polish Sociological Bulletin 57/60 (1982): 85-105.

See also individuals’ ideologies as networks; ideologies and complex systems; judgment in a world of power and institutions: outline of a view; from I to we: an outline of a theory, etc.