- Facebook57

- LinkedIn1

- Threads1

- Bluesky1

- Total 60

The numbers of jobs and college slots per capita have remained relatively stable over time, but the number of people who compete for each position has dramatically increased because markets for admissions and employment have grown (from local to national or global) and have become far more efficient. Nowadays, you can search online for jobs anywhere and click to apply.

Thus, for example:

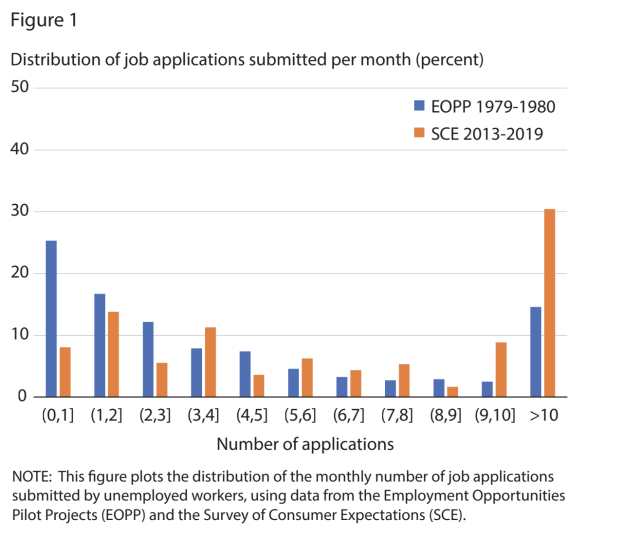

- As shown in the graph above (from Birinci, See & Wee for the St. Louis Fed), an unemployed person submitted a mode of 0 or 1 job applications per month in 1979-1980 (during a severe recession). In the 2010s, even though the unemployment rate was lower, the modal number of applications per job-seeker was more than 10 per month. Nowadays, about 2% of job applications result in an interview.

- In 1995, 10% of college freshmen had applied for admission to seven or more institutions. By 2017, 36% had done so (source).

- From the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s, the percentage of college graduates who had completed an internship rose from 10% to over 80%, probably because an internship now seems necessary to get a job (Scott Alexander, citing NACE.)

Alexander offers this pair of fictional portraits to illustrate this trend:

Brenda Boomer applied to a local business she liked at age 18. She got hired, worked her way up from the bottom, and by age 35 she was a regional manager making $50,000 per year.

Martha Millennial lost her adolescence to endless lessons in Mandarin, water polo, and competitive debate, all intended to pad her college resume; her only break was the three months she spent building houses in Rwanda to establish her social justice credentials. She eventually got accepted to Penn and earned a 4.2 in her college classes, despite having to complete several of them remotely from the Google campus where she was doing a simultaneous internship. After graduation, she applied to twenty-eight grad schools but was rejected from all of them, so she instead got two half-time jobs, one as a waitress and one at a startup that pitched itself as “Uber for humidifiers”. The humidifier startup failed, reducing her equity to $0, but she had only been in it for networking anyway, and by attending industry conferences every weekend she had collected the right contacts to get a warm introduction to the vice-president of their biggest competitor, “Uber for dehumidifiers”. She joined the dehumidifier startup, rose to associate manager, bumped up against a local ceiling (“we don’t promote from inside”), and successfully got herself poached by an air purifier startup, where at age 35 she was a regional manager making $50,001 per year.

With her “service” experience in Rwanda and her Penn degree, Martha sounds upper-middle-class. But I think we could envision a pair of working-class examples that illustrated the same trend. A low-SES Martha would apply for admission to a charter school, a slot in a summer jobs program, and an apprenticeship, not to an Ivy League university.

One might think that everything is fine for Martha. The actual odds of landing in any given social position have remained similar. With the unemployment rate at 4.4%, most people are still finding jobs. And US workers recently reported the highest mean levels of job satisfaction since they were first asked this survey question in 1987 (Conference Board 2023).

But I think the stress is very real. As a teacher and advisor of college students, I observe constant angst. Each application now generates many rejections, often with little or no feedback. Each position seems to require a different strategy, and each failure suggests that the student’s strategy must have been flawed.

Searching for educational opportunities and jobs is a substantial time commitment, a cost that may not be captured in standard economic indicators.

Finally, I think people reasonably draw negative inferences about the economy and the society from their experiences as applicants. Brenda Boomer and Martha Millennial ended up in similar jobs. But Martha competed unsuccessfully for many more opportunities than Brenda did. Almost inevitably, Martha will perceive a world of scarcity, in which desirable opportunities are out of her reach.

I wouldn’t try to persuade Martha that everything has worked out OK. She’s bound to ask, “Compared to what?” She has experienced constant comparisons to other people, some of whom have beaten her out for almost everything she has wanted to do. It’s reasonable for her to perceive a worse world than Brenda did, even if we hold all the other changes constant.