- Facebook99

- Threads

- Bluesky

- Total 99

Last week I wrote about my copy of the Rheims-Douai Bible, an English translation made by Catholics in 1582 and smuggled into Protestant England for Catholic laypeople to read. One of the translators, Edmund Campion, is now a saint, tortured to death for his secret work in England.

This Bible refutes the widespread myth that Catholics opposed translating and disseminating scripture. I think the myth sticks as a result of Protestant propaganda plus a desire to believe that religious bodies typically seek to control knowledge whereas technology (in this case, the printing press) liberates it.

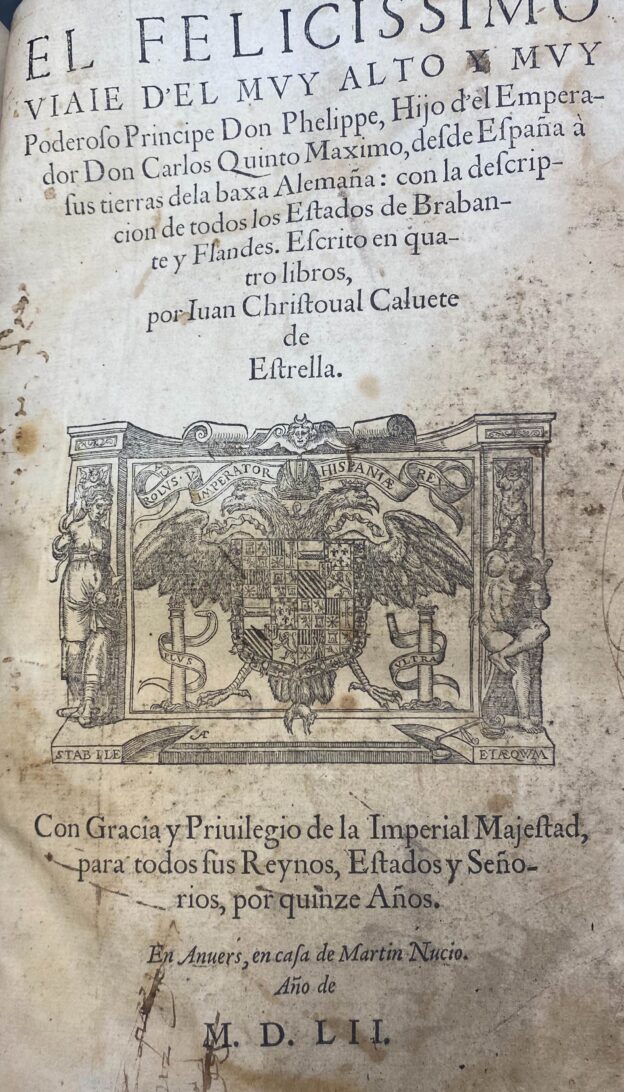

I mentioned in passing that this Bible was printed in Douai, now a city in France, which then belonged to Philip II. I also inherited from my father a 1552 volume that describes some possessions of that monarch, who later became King of Spain, King of Portugal, King of Naples and Sicily, officially the King of England and Ireland for a few years, Duke of Milan, Lord of the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands, and the colonial ruler of the Americas from New Mexico to Peru. In my translation from the Spanish, it’s entitled The Most Happy Journey of the Highest and Most Powerful Prince, Don Philip, Son of the Emperor Charles V the Great, Through Spain and His Lands in Lower Germany, With a Description of All the Estates of Brabant and Flanders.

Douay is presented on pp. 161-3. It is a “very good and well-favored [suerte] town of Gallic Flanders on the banks of the River Scarpe.” It is the site of a “good monastery” that has produced several saints. Its jurisdiction extends over many nearby villages. In mid-paragraph, the text then launches into a description of the visit by the young Philip with his father, Charles V, “who came to eat at Orchies [now in France], which was made very fresh and special with fruits and bouquets, strewn in the streets as a sign of welcome, and there the prince first ate before entering Douay. … Out of the town came the burgomasters, knights, and counselors, very well accompanied, and in the field beyond was a flag with [pisaros – ?] and drums, and there were three hundred soldiers very well ordered in colorful arms and clothing, yellow and white, and at the gate of the city the clergy processed …” — and so on for a couple more pages.

The aim is evidently propagandistic, which doesn’t imply that the authors were insincere. Perhaps they thought that Philip was a “most happy” prince of a happy empire. He did, however, face a massive uprising in his Low Country dominions.

This book was written three decades before the English Bible was printed in Douai/Rheims, but it gives a flavor of the times, which were still feudal and chivalric.

See also: A 1582 Catholic translation of the Bible into English (note #3 from the Levine library)