- Facebook404

- Total 404

Here are some working notes on Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict (Columbia University Press, 2011)

This is their central finding: nonviolent campaigns are nearly twice as likely to win–meaning that they achieve their objectives–as violent campaigns are, and the gap is growing (citing the Kindle edition, locations 315, 337).

This pattern appears to be causal; staying nonviolent increases the odds of success when other factors are held constant. Moreover, countries that have experienced successful nonviolent campaigns are much more likely to achieve “durable and internally peaceful democracies” than those that have experienced violence (351, 1260).

Why would this be? Doesn’t violence help to win many struggles? Didn’t George Washington raise an army to get George III out of the colonies? Chenoweth and Stephan argue:

- Nonviolent campaigns are less costly and dangerous to join than violent struggles, so they draw many more people. Although a few participants typically take prominent and perilous roles in a nonviolent campaign, there is also plenty of room for modest acts of support that can preserve the participants’ anonymity and safety (839). Large campaigns sometimes achieve critical mass, when the sheer size of the protests makes it safe to join–and possibly dangerous not to (812). It’s a clear pattern that bigger movements are more likely to win (892). To be sure, some people are drawn by the political potential of violence, the romance of armed struggle, or the sense that being willing to fight confers solidarity and dignity (769, citing Frantz Fanon). But the people drawn to violence tend to be young and male, and a broader base is necessary for victory.

- Nonviolent campaigns draw “robust, diverse, and broad-based membership” (351). Diversity is an asset beyond sheer numbers.

- When protests are diverse, the authorities can’t “isolate the participants and adopt a repressive strategy short of maximal and indiscriminate repression” (892). In turn, cracking down violently on a broad segment of a population often backfires. Although violent crackdowns do reduce the chance of successful resistance, they also increase the gap in the success rate between nonviolent and violent campaigns (1098, 1421). In other words, if the state is going to attack its citizens, that’s bad news, but the citizens’ smartest move is to remain nonviolent.

- Diverse campaigns typically generate a whole range of messages, tactics, and strategies, and that “tactical diversity” allows some options to succeed even if others don’t. In contrast, violent campaigns tend to make irreversible strategic decisions that prove fatal if they fail.

- A movement with diverse members is more likely to include people who have personal ties to the security forces, the government, or the business class, so it is more likely to fracture the opposition. Sixty percent of the larger nonviolent campaigns achieve “security force defections (1040). “Fraternization” is an ingredient of many campaigns’ success (1995)

- Nonviolent campaigns are much more likely to draw international support (1129).

- Authorities have sincere reasons to fear giving up power. Many former rulers have ended their lives before firing squads. Campaigns that are able to maintain the discipline of nonviolence can credibly promise to honor agreements made at the negotiating table, and that increases incumbents’ willingness to yield or share power.

As a matter of definition, we are talking about durable campaigns that have names and goals, not just events, activities, or organizations (426). Nonviolent resistance campaigns employ extra-legal activity (387), not just regular elections or lawsuits. (But sometimes a stolen election is a catalyst for extra-legal protests). They are predominantly and distinctively nonviolent, even though some violence may occur around the margins.

Chenoweth and Stephan contribute to the perennial and basic debate about structure versus agency. A structural theory explains outcomes as a result of big, impersonal forces. For instance, American presidential candidates win if the economic conditions are favorable to them, and not otherwise. It hardly matters what they do or say. An agency theory suggests that it does matter how we choose to act. A structural theory of nonviolent campaigns would attribute their success to factors like fractures in the ruling regime. Chenoweth and Stephan instead “make the case that voluntaristic features of campaigns, notably those related to mechanisms put into place by resistors, are better predictors of success that structural determinants” (1347). As I argue in my Civic Studies video, there are several robust intellectual traditions that not only find agency important in history but also work to enhance agency. Nonviolent resistance is one of those traditions.

As shown on the graph above, many nonviolent resistance campaigns fail. Although they have a surprisingly high success rate, they can still end in tragedy. One challenge is combining unity with diversity. Incorporating many kinds of people in a movement is smart; it clearly increases the odds of success. Yet movements also need unity. It can be hard to convey a coherent message or to negotiate effectively if participants in a movement disagree among themselves.

It’s also easy to overlook–when reading detached cases from distant countries–the sheer emotional difficulty of struggling together within a diverse movement. It sounds like an obviously good thing for the hard-core radicals to join together with police officials who are feeling uneasy about the regime and business interests who see new opportunities. But that’s easier said than done. Even in the relatively tame circumstances of the US in 2018, one can sense deep tensions between people who have been confronting police brutality for decades and people who joined their first protest last January and want to go home safely after the march. Making a movement out of all of them is a spiritual as well as a practical challenge.

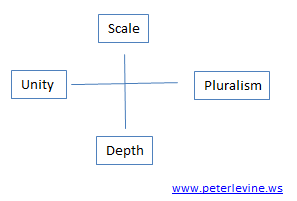

I’d interject my SPUD model here. Successful movements must combine unity with plurality, and size with depth, even though those are in tension.

Another challenge is keeping authoritarians from dominating a plural movement. The Iranian Revolution of 1979 began as truly diverse, encompassing religious revolutionaries, secular Marxists, merchants hoping for economic liberalization, civil libertarians, and even a Hippie drug counterculture (2084-2111). To achieve Unity along with all that Pluralism, the movement settled on the Ayatollah Khomeini as a leader, not because they all agreed with his positions but because he seemed uniquely viable (2111). In fact, there wasn’t much discussion in the revolution itself about what Iran should look like after the Shah (2196). This weakness became critical once the Shah was deposed, the Ayatollah gained power, and he and his allies ruthlessly destroyed all the internal opposition. The question is whether nonviolent social movements can be streams that carry authoritarians into power, and if so, what to do about it.

See also: a sketch of a theory of social movements; what is a social movement?; the kind of sacrifice required in nonviolence; and self-limiting popular politics.