- Facebook76

- Twitter2

- Total 78

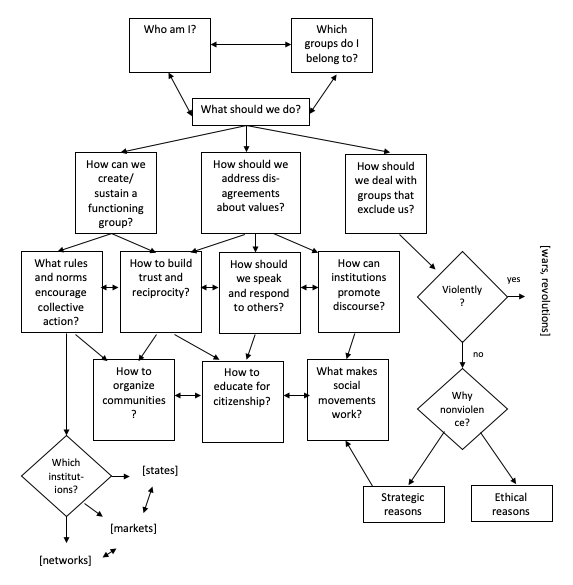

Fall 19 Civic Studies 0020-01 Intro to Civic Studies

Instructors: Peter Levine, Brian Schaffner. TA: Gene Corbin

Sept 4: Introduction

Introduction to the course and the instructors.

In class exercise: “The “Christmas Tree Crisis” at Sea-?Tac Airport” (handout in class)

Sept 9: Problems of collective action

- Timothy Burke, “How to read in college (Links to an external site.).”

- Amelia Hoover Green, “How to read political science: a guide in four steps (Links to an external site.).”

- The above readings are to help guide you in how to read what we assign in this course. The following reading is the substance of what we will be discussing in class.

- Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons.” (Links to an external site.)Science, vol. 162, no. 3859 (1968): 1243-1248.

(In class, we will simulate a collective action problem.)

Sept 11: Elinor Ostrom’s solutions to the Tragedy of the Commons

- Elinor Ostrom, Nobel Prize Lecture (Links to an external site.)(video or text)

Sept 16: Ostrom continued

- Thomas Dietz, Nives Dolsak, Elinor Ostrom, and Paul C. Stern, “The Drama of the Commons” in Elinor Ostrom, ed., Drama of the Commons, pp. 3-26.

- Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons, Ch. 1.

Sept 18: Ostrom Continued

- Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons, Ch. 3.

Sept 23: Social capital as part of the solution

- Robert D. Putnam, “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital, (Links to an external site.)” Journal of Democracy 6:1, Jan 1995, 65-78

- Robert D. Putnam, “Community-Based Social Capital and Educational Performance,” in Ravitch and Viteritti, eds., Making Good Citizens, pp. 58-95

- Pierre Bourdieu, Forms of Capital, (Links to an external site.) 1986 (excerpt)

Sept 25: Why do people voluntarily participate?

- Inglehardt et al., “Declining willingness to fight for one’s country: The individual-level basis of the long peace,” Journal of Peace Research

- Russell J. Dalton, “Citizenship Norms and the Expansion of Political Participation, (Links to an external site.)” Political Studies

Sept 30: Discussing good ends and means

Reading assignment: the Harvard Pluralism Project’s case entitled A Call to Prayer (Links to an external site.). In the discussion sessions this week, students will deliberate what the people of Hamtramck, MI should do. In the class session on Sept 30, additional discussion of deliberation (what it is, what it can accomplish, and what else is needed for good decision-making).

Oct 2: Habermas and Deliberative Democracy

- Jürgen Habermas, “The Public Sphere: An Encyclopedia Article,” New German Critique, 3 (1974), pp. 49-55

- Lasse Thomassen, Habermas: A guide for the perplexed. A&C Black, 2010, pp. 63-96, 111-130.

Oct 7: Does deliberation work?

- Dennis Thompson, “Deliberative Democratic Theory and Empirical Political Science,” (Links to an external site.) Annual Review of Political Science

- Michael A. Neblo et al., “Who wants to deliberate—and why? (Links to an external site.)”, American Political Science Review.

Oct 9: Other forms of discourse: 1) testimony and empathy

- Lynn Sanders, “ Against Deliberation” (Links to an external site.)

- Emily McRae, “Empathy, Compassion, and ‘Exchanging Self and Other’ in Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Ethics” for Handbook of Philosophy of Empathy (Routledge), edited by Heidi Maibom, 2017.

[Oct 14: vacation day]

Oct 15 (Tuesday): Other forms of discourse: 2) dissent

- Tommie Shelby, “Impure Dissent” from Dark Ghettoes: Injustice, Dissent and Reform (2016)

Oct 16: How can we design for deliberation?

- Tina Nabatchi, Matt Leighninger, Public Participation for 21st Century Democracy (2015), pp. 241-285 and 305-324

Oct 21: Midterm in class

Oct 23: Exclusion and Identity

- The Book of Nehemiah (Links to an external site.)

- Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House. (Links to an external site.)

- ”Steve Biko, “Black Consciousness and the Quest for a True Humanity“

Oct 28: What happens when people experience diversity?

- Craig et al., “The Pitfalls and Promise of Increasing Racial Diversity: Threat, Contact, and Race Relations in the 21st Century (Links to an external site.),” Current Directions in Psychological Science

- Elizabeth Levy Paluck, “The contact hypothesis re-evaluated, (Links to an external site.)” Behavioural Public Policy

Oct 30 Guest lecture on political hobbyism (Eitan Hersch)

- Eitan Hersh, “The Problem with Participatory Democracy is the Participants,” New York Times.

- Eitan Hersh, “In a Deep Blue or Red State? You Can Still Influence Politics,” New York Times

Social Movements

Nov 4: Identity and the Common Good

- Lilla, Mark Lilla, “The End of Identity Politics (Links to an external site.),” The New York Times, Nov. 18, 2016

- Todd Gitlin, “The Left Lost in Identity Politics (Links to an external site.),” Harpers, Sept. 1993

- Transcript of an encounter: Hillary Clinton and Julius Jones

Nov 6: Social Movements

- Charles Tilly, “Social Movements, 1768-2004“

- Marshall Ganz, “Why David Sometimes Wins: Strategic Capacity in Social Movements,” in Jeff Goodwin and James M. Jasper, Rethinking Social Movements: Structure, Meaning, and Emotion (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2004) pp.177-98.

(Nov 11: no class)

Nov 13: Community Organizing

- Schutz, A., & Sandy, M. (2011). Collective action for social change: An introduction to community organizing. (Links to an external site.)New York: Palgrave MacMillian. [Note: We will upload a PDF–link to Google Books in place for now].

- Cortés, Ernesto. 1994. Reweaving the social fabric. The Boston Review (Links to an external site.) 19 (3).

Nov 18: Nonviolent Campaigns

- Martin Luther King, Stride Toward Freedom, chapters 3, 4, and 5.

- Timothy Garton Ash, “Velvet Revolution: The Prospects,” New York Review of Books, December 3, 2009

Nov 20: Gandhi

- Bikhu Parekh, Gandhi, Chapter 4 (“Satyagraha”), pp. 51-62;

- Gandhi, Satyagraha (Ahmedabad: Navajivan Publishing Co., 1951), excerpts.

Nov 25: Gandhi continued

- Gandhi, Notes, May 22, 1924 – August 15, 1924, in The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (Electronic Book), New Delhi, Publications Division Government of India, 1999, 98 volumes, vol. 28, pp. 307-310

[Nov 27: no class]

Dec 2: Does nonviolence work? Does violence work?

- Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict,chapters 1 and 2

- Enos et al., “Can Violent Protest Change Local Policy Support? Evidence from the Aftermath of the 1992 Los Angeles Riot (Links to an external site.),” American Political Science Review

Dec. 4: Student presentations in class

Dec 9: Student presentations in class

Dec 17: Final exam (3:30-5:30 in the Rabb Room)

(click for more information)