- Facebook276

- Total 276

This summer, I’ve had the chance to lead discussions among 20 scholars and activists who gathered for two weeks at Tufts, to chair the Frontiers of Democracy conference for about 130 educators and organizers (mostly Americans), to work with social studies teachers in Utah and in Ukraine, and to participate in the 4th annual European Summer Institute for scholars and activists from Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Germany, Kazakhstan, Kirghistan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Ukraine. I got to meet more than 200 new people, almost all of whom would say that their vocation is to support democracy.

These conversations provoke reflection on my part, a quarter century after I started in the “democracy business” at Common Cause and then at the University of Maryland’s School of Public Policy. It strikes me that our agenda must be very different today from during the Bush I and Clinton years, when I was in my 20s and early 30s. I’ve perhaps been too slow to adjust to the change (the Obama years made me complacent), but it’s not too late.

In the late 1900s, the formal systems of parliamentary democracy seemed secure in countries like the US, and triumphant globally. Autocrats were old guys who couldn’t deliver prosperity, achieve popularity, or anticipate the social movements that toppled them.

However, politics and government were unpopular in the US. We weren’t using public institutions to tackle complex and profound problems, such as de-industrialization, racial injustice, or environmental crises. Maybe that was because the neoliberal center-left–leaders like Clinton and Blair–had simply given up. Or maybe it was because citizens had come to mistrust public institutions for good reasons, and the tools and processes of government were inadequate to the challenges of the day.

Meanwhile, everyday civic life had eroded. Robert Putnam suggested this erosion in “Bowling Alone” (1995); succeeding events have unfortunately vindicated him. Traditionally, formal politics in the US rested on a foundation of associations that brought people out of their private spheres and taught them values and skills relevant to national government. Those associations had shrunk and fractured.

Many of us thought that we should try to “deepen” democracy by adding to the formal processes of our political system better opportunities for citizens to discuss and collaborate. That would repair some of the gaps among citizens and between citizens and the state and would enable civil society to tackle intractable problems. This was the premise of the National Commission on Civic Renewal, of which I was deputy director (1997-8), and of my 2000 book, The New Progressive Era: Toward a Fair and Deliberative Democracy.

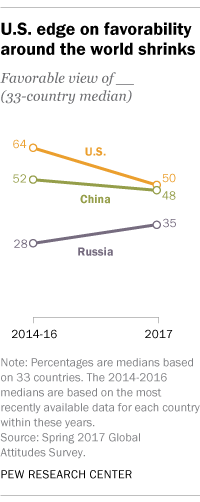

Flash forward to 2018, and we observe a very different situation. The autocrats and oligarchs are now the innovators, delivering prosperity and popularity in countries like China. Freedom House argues that democracy has been in retreat for a dozen years. As influential as the book version of Bowling Alone was in 2000 is this year’s How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt.

Then, one of the concerns was US arrogance and ideological imperialism, as we sent legions of advisers to places like the former Soviet Union and discussed the End of History thesis. We “spiked the football” in the end-zone of the Cold War. Now China offers the model that has rising global appeal: sophisticated technocratic authoritarianism, a corporate-dominated market economy, and assertive nationalism. The US follows that global trend but in a version that inspires almost no one beyond our borders.

Many people don’t merely disapprove of the performance of their respective democratic governments; they explicitly disparage democracy. Whereas every Republican president from TR to George W. Bush (except perhaps Taft) presented himself as a champion of democracy (by that name), now only one of the major American parties consistently endorses democracy as an ideal.

Americans are not merely disengaged and a little mistrustful of one another; we increasingly hate each other.

In the modern world, we observe events not directly, but through media of communications. Those media have been massively transformed since the late 1900s. One third fewer people are employed at journalists today, metropolitan daily newspapers have virtually collapsed, and the global media environment is dominated by openly ideological broadcast companies and caustic social media.

We’ve made some progress on some social issues (health insurance, for instance), but other issues have reached the boiling point. Policing, for example, was racially unjust in the 1990s. People then demanded the execution of innocent young Black men and defended their stance by saying, “maybe hate is what we need if we’re gonna get something done.” But now the person who uttered that particular phrase is the President of the United States and has the explicit support of more than 4 in 10 Americans.

I am increasingly skeptical that our main need is to deepen democracy–to add forums, programs, or policies that grant citizens more valuable roles in our formal systems. I doubt that strategy would block Brexit or Trump or the purge of the Supreme Court in Poland. Deepening democracy might work for addressing a mild sense of alienation from routine governance, but not for holding back autocracy.

If mishandled, this strategy can even help to delegitimize institutions that deserve support. Caroline W. Lee argues that organized deliberations can co-opt resistance. Cristina Lafont worries that deliberative fora can delegitimize regular democratic processes, such as elections, by making them look so inferior that they don’t deserve protection. China is implementing local deliberative processes at a large scale, perhaps to blunt criticism and improve satisfaction with its regime.

I think the new wave of strategies must have these features:

- Democracy must be championed by candidates, parties, and movements that aim to govern, not by specialized nonprofits in the democracy field. We can’t be satisfied with procedural innovations around the edges. Governments must demonstrate that they can get better outcomes by using democratic methods. That means that the same people must offer procedural reforms, democratic values, and substantive policies, and they must deliver results while they hold power.

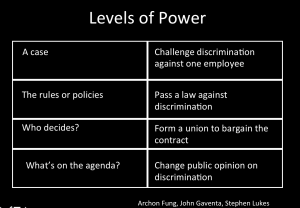

- Democratic reforms must shift the balance of power. That means that democracy can’t be viewed as politically neutral or nonpartisan. Some people must gain influence at others’ expense, to even the balance.

- Our strategies must address formal processes and rights guaranteed by constitutions–not add-ons.

- We should make more use of direct action and contentious social movement tactics.

- Arguments for democracy must be enthusiastic assertions of human dignity, fairness and equity, decency and non-corruption. They can’t be technocratic, legalistic, or procedural arguments, nor can they be hedged with qualifications. Human beings (everywhere) simply have a birthright to be treated as owners of their societies.

In many countries, the torch can be carried by new parties with explicitly democratic values and policy agendas. Pedemos (left) and Ciudadanos (center-right) both fit that bill in Spain.

In the US, the most important struggles involve our existing parties. The Democrats must win in 2018 and 2020, must then govern competently, must articulate a persuasive vision of an inclusive democracy, and must shift from making social policy reforms (like Obamacare) to changing who has power through electoral and labor-law reforms. They must address the third level of power.

Meanwhile, conservatives must capture the Republican Party for a genuinely conservative agenda of decentralization, constitutionalism, and skepticism about government. This may sound like “concern trolling“: a liberal pretending to care about the GOP to score points against it. But I genuinely believe that the struggle of true conservatives for their party is one of the most important frontiers in the US today.

See also: people trust authoritarian governments most; why autocrats are winning; what does it mean to say democracy is in retreat?; and why the deliberative democracy framework doesn’t quite work for me.