- Facebook440

- Total 440

I’m working with an interdisciplinary team* on a project that’s investigating whether an arts center in Boston’s Chinatown can mitigate the negative effects of gentrification in that neighborhood. This research is funded by the NEA and by Tufts (through a “Tufts Collaborates” grant). Here are some preliminary notes, with which my colleagues may not necessarily agree. We have much more data to collect, analyze, and discuss.

The setting is Boston’s Chinatown. The Asian population of the neighborhood has declined, the median income of Whites in the neighborhood has more than doubled, but the percentage of Asian households living in poverty has increased. These could be seen as signs of gentrification.

The Pao Arts Center is a new “multi-functional arts space with a performance theater, an art gallery, classrooms, an artist-in-residence studio, and other public meeting spac e[s].” It has been created within a very large, multipurpose new building that includes affordable housing along with expensive apartments (which have a separate entrance). The building reflects the shift toward more expensive, modernist, large-scale development in Chinatown. It also belongs to a community-based nonprofit, the BCNC [correction: the Asian Community Development Corp. was the community developer; BCNC leases the space for Pao] that offers programs to about 2,000 families and is committed to retaining the cultural heritage of the neighborhood and combating dislocation, isolation, and conflict.

e[s].” It has been created within a very large, multipurpose new building that includes affordable housing along with expensive apartments (which have a separate entrance). The building reflects the shift toward more expensive, modernist, large-scale development in Chinatown. It also belongs to a community-based nonprofit, the BCNC [correction: the Asian Community Development Corp. was the community developer; BCNC leases the space for Pao] that offers programs to about 2,000 families and is committed to retaining the cultural heritage of the neighborhood and combating dislocation, isolation, and conflict.

You might begin thinking about this project with the following model in mind:

- Gentrification disrupts community connections, which causes harmful social outcomes (apart from any other outcomes that gentrication may have). But …

- The arts can strengthen community connections, thus mitigating the damage done by gentrification.

But the emerging data complicate this model.

The neighborhood is dynamic. People move in and out as both a cause and a consequence of economic change. It’s possible for an individual to remain in Chinatown and move on a trajectory of upward (or downward) mobility, while assimilating (or not assimilating) to the dominant culture. It’s also possible for an individual to leave in order to take advantage of a desired opportunity–or as a matter of necessity, due to rising rents.

The whole neighborhood could be characterized as historically Chinese-American. It was never like a traditional community in China; it was an enclave of Victorian tenement buildings, manufacturing plants, and restaurants catering to outsiders in an East Coast US city. One evident change is that it’s becoming much more pan-Asian. Does that preserve its heritage as an ethnic enclave or spell the end of “Chinatown” per se?

By no means everyone in Chinatown embraces the concept of “gentrification.” I think that word is almost always defined as a negative trend, a process of disruption or displacement caused by outside forces and suffered by residents of a neighborhood. In We Were Eight Years in Power, Ta-Nehisi Coates calls gentrification “a more pleasing name for white supremacy.” (But see also his nuanced piece on the same topic from 2011). However, there is a different discourse that emphasizes economic growth and development and upward-mobility. Some people in Chinatown see rising rents and residents moving out to suburbs as signs of progress, attributable to their own success rather than outside forces.

The neighborhood is certainly changing its physical form. Even presuming that most tenants of the new BCNC high-rise are Chinese-American former residents of other Chinatown buildings, the sheer design and aesthetic of their home are new. There are similar buildings in modern Shanghai (and in modern Dubai and Mexico City), but not in a traditional Chinese-American neighborhood in a Northeastern city like Boston. Is this preservation? Development?

Likewise, the Pao Arts center is devoted to Asian arts, but its minimalist and functionalist architecture could be seen as modernist, cosmopolitan, placeless, or specifically “Western,” depending on your interpretive frame. Pao probably feels different to people of different backgrounds.

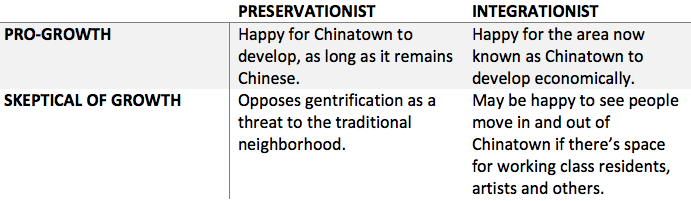

There may also be differences between groups that I will call (with some concerns about these labels) preservationists and integrationists. Preservationists see value in an historic Chinese urban enclave, whereas integrationists may celebrate the arrival of other Asians and non-Asians in Chinatown and the positive effects that occur when Chinatown residents move to suburbs.

These two distinctions produce four possible stances, but in real life, many more options are possible.

To further complicate the model, it’s not a simple case of “the arts” affecting a neighborhood. The Pao Arts Center hosts many events and exhibitions. Our team has been attending the events and conducting surveys, and it seems clear that various events draw different demographic groups and have different purposes and impact. Some performances raise consciousness of social injustice; some are sheer fun. Also, these are not exactly Pao Arts Center productions: Pao is a space that various artists and organizations use.

A series of events at Pao could reconnect people who have moved away from Chinatown to their former neighborhood, give local Chinese residents a reason to stay in Chinatown or mitigate the stress caused by changes in the area, connect people of different Asian backgrounds or of different races to one conversation and one affective community, or serve a diverse set of audiences from the Boston metro area without really having much to do with connections or the immediate vicinity. Pao could contribute to neighborhood economic development, thus accelerating gentrification, or it could consolidate Chinatown’s function as an ethnic enclave. It could do more than one of these things for different people at different times.

We have survey data from audiences, interviews with artists and other key stakeholders, pending surveys of community-members, and expert analysis of the events. We still have to put it all together.

*Cynthia Woo (Pao Arts Center), Ginny Chomitz (Tufts Department of Public Health and Community Medicine), Carolyn Rubin (Public Health and Community Medicine), Susan Koch-Weser (Public Health and Community Medicine), Annie Chin-Louie (Tufts Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute), Noe Montez (Tufts Department of Drama & Dance), Yizhou Huang (Drama and Dance), Yang He (Tufts Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning), and Joyce Chen and Kaiyan Jew (community researchers).

See also changes in how we talk about cities; against methodological individualism or why neighborhoods are not like broccoli; why the Jews left Boston, why the Catholics stayed, and what that teaches us about organizing.