Today at a Social Science Education Consortium meeting, Walter Parker is presenting his fine paper with Sheila Valencia and Jane Lo entitled “Going for Depth in Civic Education: A Design Experiment,” and I am replying.

Parker and colleagues have completely redesigned the AP American Government class–often a rapid march through miscellaneous material–so that it employs nothing but elaborate simulations (a model Congress, a mock Supreme Court, etc.) and focuses on a few central concepts instead of a long list.

The results have been positive: students perform just as well on the AP test while developing much more civic skills and interests. I love the move to interactive projects and the willingness to distinguish central from peripheral concepts. I also agree with Parker and his colleagues that if the course is AP American Government, then the core concepts are “federalism and constitutional reasoning.” Working with those concepts in interactive settings will teach you what you need to know to score high on the test.

The question is whether these should be the core concepts if we have one chance to teach civics to high school seniors. I can think of three major reasons that they should be:

- Americans should understand federalism and separation of powers as major aspects of our constitutional system, because the constitution determines our politics.

- Americans will be more effective if they understand these concepts. For instance, if you understand federalism, you won’t contact your Member of Congress to report a broken streetlight on a state or city road.

- Americans should honor the basic values of constitutional government, which include obeying the rules that constrain us and recognizing the value of limitations on the power and discretion of each person and office.

Here are my reasons to doubt, or at least to complicate, these arguments.

First, the US Constitution is not very well designed for our era. I am not primarily talking about its undemocratic aspects, such as the highly unequal significance of a vote in different states. That is a planned feature, not a bug. Instead, I am talking about the bugs.

For example, if the president and Congress belong to different parties, no coherent policy is possible, and all the incentives favor each side sabotaging the other. Juan Linz found that the US was the only presidential republic that hadn’t already collapsed into a dictatorship. The reason may have been lucky circumstances (vast ideological diversity within each party) that allowed US presidents to form working majorities regardless of which party controlled Congress. Those days are gone.

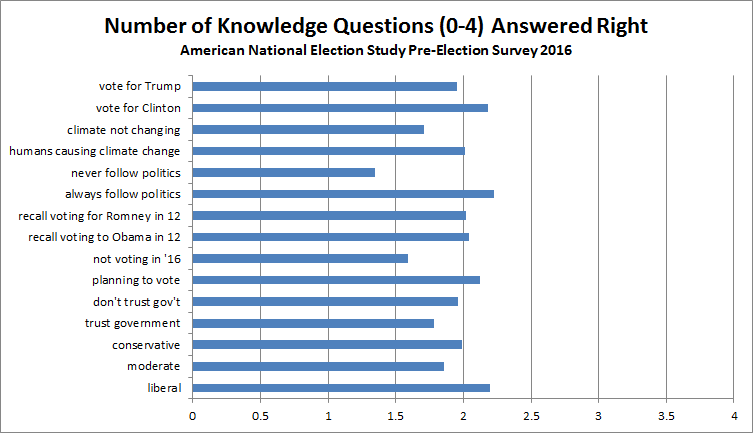

Likewise, the Constitution fails to acknowledge such crucial components of our modern polity as parties, general purpose corporations, lobbies, media companies, administrative agencies, security agencies, and nonprofits. Our jury-rigged system copes by treating parties, companies, and nonprofits as First Amendment “associations,” media companies as “the press,” and federal agencies as arms of the president. This doesn’t work very well. Therefore, learning the official theory of the Constitution does not help a citizen to understand how things actually work; and learning how things work does not reinforce trust in the official theory. (See yesterday’s post on the small negative correlation between political knowledge and trust in government.)

Second, learning the official rules doesn’t help you navigate the system all that well. A very common assignment (or assessment question) asks students to choose which branch or level of government to contact about various topics of concern. But that’s not how things really work. Your Member of Congress might be the best person to ask about a significant road repair if you know her; she can call a city official and get it fixed. Your Representative is not worth contacting about a federal issue if she she has taken a hostile position on it or if the issue is off the table. Effectively navigating the system involves answering such questions as: What is being decided, by whom? Whose interests align with yours? Whom do you know? Whom do you know who knows someone else who knows an actual decision-maker? What does the press care about? Is there an organization that might take an interest in your issue? I fear that by teaching the official theory, we actually give the wrong impression of how a bill becomes a law. (A question for Walter is whether simulations of governmental processes primarily teach the official rules, or skills like persuasion, or both.)

Third, I am not sure that the values implied in a curriculum about separation of powers are the most important ones for students to learn. We do want people to honor the best principles that underlie a constitution like ours, such as rule of law and limits on powers. Our president never acknowledges that he should be limited in these ways, which is one of the reasons that I consider him anti-conservative. Citizens who understand the importance of limits may be less likely to assess politicians in unreasonable ways–expecting them to accomplish things that they are prevented from doing.

However, these principles may not be the paramount ones for everyday citizens (as opposed to presidents of the United States). Citizens should also honor such principles as personal responsibility for the world, openness to alternative views, concern for facts, and fairness. I am worried that by emphasizing constitutional values that mainly pertain to office-holders, we encourage students to think like states, when they should above all think like citizens.

See also: is our constitutional order doomed?; the Citizens United decision and the inadequate sociology of the US Constitution; liberals, conservatives, and love of the Constitution; constitutional piety.