- Facebook146

- Total 146

Notwithstanding the fiasco that is the GOP presidential primary so far, Matthew Yglesias warns, “The Democratic Party is in much greater peril than its leaders or supporters recognize, and it has no plan to save itself. … The vast majority — 70 percent of state legislatures, more than 60 percent of governors, 55 percent of attorneys general and secretaries of state — are in Republicans hands. And, of course, Republicans control both chambers of Congress.”

A major factor is the turnout gap. That is worse for Democrats in local and off-year elections but will persist in 2016. Today, the pollsters Greenberg/Quinlan/Rosner report that “unmarried women, minorities, and particularly millennials are less interested in next year’s voting than seniors, conservatives, and white non-college men are.”

Why do we see these gaps? On the whole, we engage in politics when we are brought into networks where political issues are regularly discussed and where people encourage each other to participate. This is a consistent finding of our own research on youth as well as much research on adults. Yglesias uses that theory to explain why unionized teachers vote in local elections:

Teachers talk to one another (they work together, after all) about questions of public policy (everyone talks at work about work, but public school teachers’ work ispublic policy), and they also have hierarchical channels of information dissemination (the union itself) through which this work talk can connect to practical politics.

(Yglesias is expanding on Eitan Hersh’s argument that “scheduling local elections at odd times appears to be a deliberate strategy aimed at keeping turnout low, which gives more influence to groups like teachers unions that have a direct stake in the election’s outcome.” Yglesias is contributing an explanation of why the union members vote.)

Let’s call participation in networks “social capital.” Since the 1970s, Democrats have lost social capital (of a politically relevant kind) and Republicans have not. The parties used to be on par, but the Republicans now have a meaningful advantage.

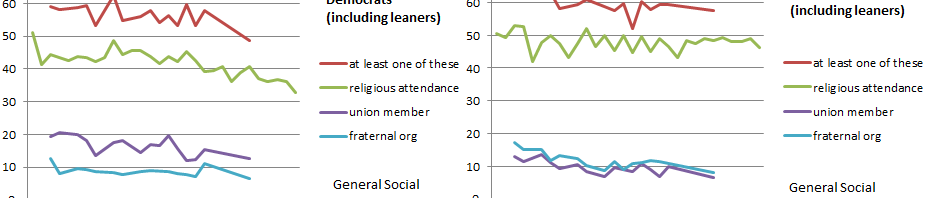

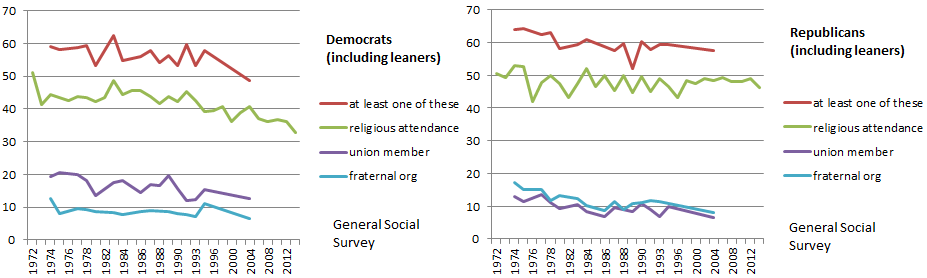

To illustrate, I show rates of regular religious attendance, membership in unions, membership in fraternal organizations, and a composite (defined as belonging to at least one of the three). The data come from the General Social Survey, which hasn’t asked about unions or fraternal associations since 2004. But in some ways, that’s OK, because I think the trend from 1970-2004 is the significant one, and the subsequent period has been unsettled because of social media and two high-profile presidential elections.

Observations:

- Democrats have become less likely to attend religious services regularly; Republicans have not.

- Democrats have always been more likely than Republicans to belong to unions, but their membership rate was considerably higher in the 2000’s than in the 1970s. (Of course, union membership for Americans as a whole has fallen more steeply.)

- Republicans have lost some ground with fraternal associations, but those never provided a huge component of their social capital.

- The Democrats show an overall decline; the Republicans do not.

Caveats: 1) These are only three measures of social capital, plus a composite of the three. There are certainly other varieties of engagement–but I selected the ones I thought were most important. 2) Democrats and Republicans are not fixed demographic groups with persistent members. It is not the case that people have remained Democrats but have become less likely to join unions or attend church. Rather, the American people have changed in various ways, and the subset that consists of Democrats who have social capital has shrunk. The trends shown above only tell part of the story, but I think an important part.