- Facebook68

- Total 68

I am enjoying Elizabeth McKenna’s and Hahrie Han’s book Groundbreakers: How Obama’s 2.2 Million Volunteers Transformed Campaigning in America in preparation for this free open forum in Chicago on May 19. Register here.

I am enjoying Elizabeth McKenna’s and Hahrie Han’s book Groundbreakers: How Obama’s 2.2 Million Volunteers Transformed Campaigning in America in preparation for this free open forum in Chicago on May 19. Register here.

We discuss in order to address public problems together. We also develop morally through discussion–which, by the way, I would define very broadly to encompass a conversation with your neighbor over the backyard fence, with Leopold Bloom in the pages of Ulysses, with Angela Merkel through the New York Times, with Jesus in prayer, or with your late parent through memories and imagination.

I posit that the quality of discussion is a function of the skills, attitudes, and beliefs of the participants; the nature of the question under consideration; and the format. An individual’s contribution to a good discussion must be understood in context, because a given discursive act (such as making a concession or repeating a claim) can either be helpful or harmful, depending on the situation.

The tool I would use to assess discussion is a network map, where the nodes are the assertions made by the participants, and the links are explicitly asserted connections, such as “P implies Q” or “P is an example of Q” or “P is just like Q.” The network grows as the conversation proceeds–except when people stop adding new ideas and links–and each contribution can be assessed in terms of how it changes the network. A person’s statement can (for example) make a network larger, richer, denser, or more coherent.

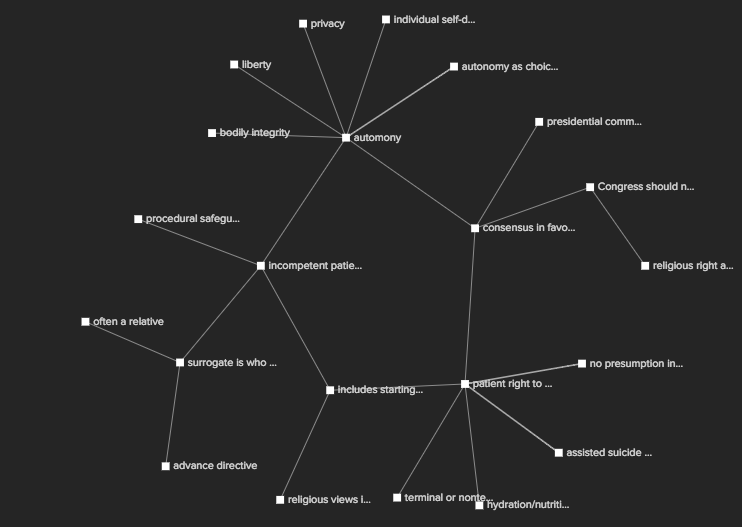

As an illustration, I’ve mapped a 2005 Pew Research Center debate on the right to die (prompted by the then-recent Terry Schiavo case) that involved Daniel W. Brock (a medical ethicist), R. Alta Charo (a law professor), Robert P. George (a political theoriss), and Carlos Gómez (a hospice physician). The transcript is here and my map can be explored here:

This topic (end-of-life decisions) has certain features: it raises fundamental metaphysical questions rather than empirical questions that could be settled with data. It poses absolute and irrevocable decisions, unlike questions about the distribution of scare resources, which can be negotiated. As for the format, it involved relatively long prepared statements by just four experts, in contrast to a free-for-all among a larger group, which would have a different structure. And the speakers, although diverse in perspectives, were all accustomed to a certain style of argument (relatively abstract and organized). It would be interesting to contrast this transcript to, for instance, a New England town meeting about a budget.

Dan Brock goes first and has a chance to lay out a position in favor of allowing a patient or her surrogate to end life support. His position is neatly organized, with the principle of autonomy at the center. He names that principle as the underlying rationale for a series of professional reports and court decisions that represent what he calls the current consensus. He connects autonomy to several related concepts: bodily integrity, privacy, self-determination, and choice. He draws the explicit implication that an autonomous patient must be able to choose or refuse any treatment. He adds the idea that when a person is incapable of exercising autonomy and has not made an advance directive, the best course is to empower a surrogate to choose. And he denies that the patient’s or surrogate’s choice should be constrained by supposed distinctions between starting versus stopping care, hydration/nutrition versus medical treatment, or a terminal versus a stable condition. Below is his position, isolated from the rest of the network.

Brock’s position is consistent (no nodes contradict each other), coherent (all nodes are connected), and centralized around the concept of autonomy. I would attribute those features of his position to: 1) the format (he gives prepared remarks that come first in a debate), 2) the professional style of the speaker (a professional philosopher), 3) the nature of the topic (bioethics), and 4) Brock’s position as a liberal who strongly favors autonomy. Indeed, Robert P George, the conservative theorist, says later in the debate: “liberals have to come up with a justification for placing autonomy in the central position in the first place, and that requires the defense of a moral proposition.” Note George’s use of a network metaphor to characterize Brock’s view.

Dr. Carlos Gomez speaks second. Unlike Dan Brock, he doesn’t produce a single, organized argument with explicit connections than link all of his ideas. I count nine different clusters of points in his remarks. Gomez’ points–isolated from the rest of the network–are shown below.

An important claim for Gomez only becomes evident to me (although this might be my own limitation as an interpreter) during the following exchange from the Q&A:

MODERATOR: Actually, before we go to the next question, when you said autonomy misses something essential in this sort of doctor-patient relationship, would you elaborate a little bit more on what that means in the real world?

MR. GOMEZ: Yeah, I’ve never had a patient knock on my office door, come in, sit down, and say, “I’m here to exercise my autonomy.” Now I may be a little too glib there, but what I’m suggesting is that one of the reasons that they are coming to me is precisely by nature of what I profess as a physician, by nature of what I know in terms of my skills, and also by nature – and on this I think Robby is dead on – by nature of the fact that there is a moral construct to what it means to be a physician or a nurse, or any other professionals that professes publicly what they’re going to do.

I think what Carlos Gomez has been implying all along is that nurses and doctors are required to show care for a patient, and an ethic of care is inconsistent with ending the patient’s life. Further, caregivers should have a strong voice in the debate about bioethics. Unlike Dan Brock, however, Gomez does not present that position as an organized argument but alludes to it with relatively scattered claims about how, for instance, there is actually no consensus about end-of-life treatment and the press is uninformed about hospice care. If I were to evaluate Gomez’ participation, I would say that he is less rhetorically effective than he might have been because he never states a claim that actually is central for him. The moderator assists not only Gomez but also the group by drawing out one central node that had not been clear before. On the other hand, Gomez clearly contributes ideas to the conversation and connects many of them to points already introduced by Dan Brock; so he broadens and enriches the discussion.

Alta Charo, a law professor, speaks third. She makes a cluster of points about how people mistake biological patterns for moral imperatives, and a related cluster of points about how sometimes the law appropriately creates “fictions” that are not based on biology, such as the idea of adoptive parenthood. She also makes at least nine other points that don’t explicitly connect to these two clusters. Her view is about as coherent as Carlos Gomez’. However, she is in a different position from him. She generally holds the same liberal position as Dan Brock, who has already spoken. It would not contribute to the conversation for her to repeat Brock’s argument for the centrality of autonomy, although she does state that choices about life must be personal and free. Instead, she builds ideas around the structure than Dan Brock has already laid out.

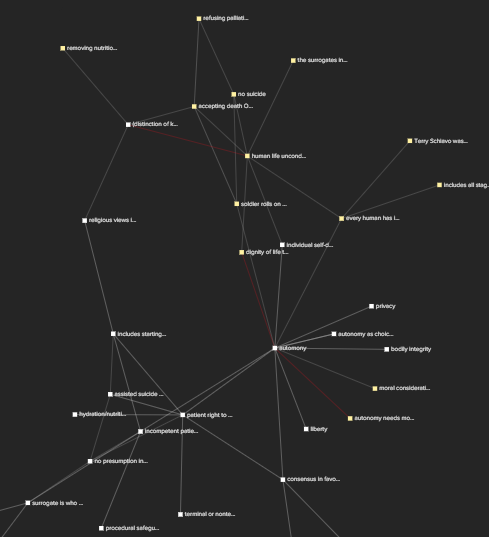

George follows Charo, and he lays out an alternative view to Brock’s, in which autonomy is explicitly not the central idea. Instead, “human life, even in developing or severely mentally disabled conditions, [is] inherently and unconditionally valuable.” His structure is about as consistent, coherent, and centralized as Brock’s, but it has a different center. Below is shown a network consisting only of the ideas proposed by Brock and George. “Human life is unconditionally valuable” is a central node in the top third of the picture; autonomy is a different center about two-thirds down.

The two networks touch at multiple points, either because George contradicts Brock (I show explicit disagreements with darker lines) or because he acknowledges specific areas of agreement.

Later, in the Q&A, George makes a discursive move that can sometimes be helpful to a group. He says, “As much as I love disagreement and dissent, I think that on one point on which Carlos and Dan thought they were arguing, there’s not actually a disagreement.” This is an example of tying together two points that have already been made in order to increase the coherence of the network. It is a helpful move–unless the two points are not actually alike.

By the time the session ends, the whole network is fairly connected. But certainly, no agreement has been reached, and two nodes remain central for different people but mutually inconsistent. That may be an inevitable feature of debates about the ends of life, or it may be a function of the way these speakers reason about such questions. Although they are speaking lightly at this juncture, Brock and Gomez imply a serious point about the impasse between them:

Dan Brock: Well Carlos and I first met on a PBS show about assisted suicide I guess 15 years ago, was it, Carlos? And we disagreed then roughly the way we do now, so –

MR. GOMEZ: I’m unteachable.

MR. BROCK: So am I.

I would hope that more mutual learning can occur when issues are either more empirical or more negotiable than this one is.

We come into the world with no moral ideas at all and must learn them from others. We learn not just from arguments and explicit principles, but also by observing practices and experiencing emotional reactions.1 We must make judgments about complex, evolved, historically contingent phenomena (such as, among many others, marriage, democracy, and art) that we cannot apprehend as wholes but must learn to assess from accumulated and vicarious human experience.2 In Habermas’ terms, we begin with a “Lifeworld” formed of our shared experiences and improve it through explicit deliberation with diverse people in civil society.3

Some people are much better at this process than others are, and we can explain why by understanding their moral worldviews as networks of ideas and connections and considering how their whole networks are organized. Consider these hypothetical discussion partners:

This list can be extended. The point is that the structure of a moral network is important. That follows from the premise that we each begin with whatever ideas and connections we happen to hold, and our responsibility is to refine the whole set in discussion and collaboration with others. In that case, we should be concerned not only about the various values that we endorse, but also with how they are configured. The best networks for discussion are likely rich, complex, connected, not overly centralized, and not necessarily fully consistent.

Notes

Many of my friends and colleagues believe that the more democratic any institution is, the better. I take a more pluralist position: democratic values are worthy but they are inconsistent with other values, and what we want is a mix of institutional types.

You can’t enter this debate without having a definition of “democracy” in mind. I would reserve the word for any system that defines a group of people (the demos) and empowers them all to rule (the “-cracy” part, from kratein) with roughly equal influence or authority over the outcomes.

Voting is neither necessary nor sufficient for democracy. It isn’t necessary because other devices, such as lotteries, common property regimes, and consensus decisions, can also afford everyone equal influence. And it isn’t sufficient because a vote can’t achieve its purported purpose without various supports. These supports include at least freedom of speech and assembly and also (I would assert) universal education, an actual press that performs its role well, an independent judiciary, habits of deliberation, and enough social equality that no caste, class, race, or gender is able to dominate the discussion because of its perceived superiority. Social equality may, in turn, require at least a limited degree of economic equality. These conditions are highly debatable, but it’s pretty clear that at least some of them are necessary.

Democracy embodies at least two valid principles: 1) equal respect for the dignity of all people, and 2) a general presumption that decisions made by the demos will be wiser, or more just, or at least less corrupt and self-serving than decisions made in other ways. These two democratic principles are always worth considering, whether you are involved with a firm, a neighborhood, a church, a university, a family, or a scientific community.

But they are not the only valid principles. You should also consider: liberty, solidarity, excellence of various kinds, truth, diversity, peace, rule of law (which implies stability and predictability), psychological and material wellbeing, intimacy and privacy, efficiency, the interests of future generations and animals, and–if you are so oriented–God.

Alas, these various principles do not fit neatly together but often trade off. For instance, empowered groups can easily suppress individual liberty or ignore the rule of law. So how should we decide how to make the tradeoffs? A superficially appealing answer is: “Let’s decide democratically.” But democratic processes are biased in favor of the democratic principles over the other ones. Likewise, market processes are biased in favor of efficiency and liberty; scientific processes privilege truth and certain kinds of excellence; legal processes favor rule of law.

The cautious, pragmatic solution is pluralism. Let there be powerful democratic institutions and also intentionally undemocratic ones, where the latter category includes physics departments, for-profit startups, hierarchical churches, anarchistic commons, and many more. Assign decisions about certain broad questions of distributive justice to democratic institutions. But limit the scope of democratic decisions with a strongly liberal constitution that defends pluralism.

This is very far from an original or idiosyncratic position, but it may be useful as a dissent from the “strong democracy” thesis that is pervasive in some circles I move in. It also suggests a more capacious definition of “the civic” or “civic engagement.” I use these phrases to mean not democratic participation but rather creative love for the world. It is a secondary question whether the best way to improve the world (in a given situation) is democratic. Sometimes it is, but definitely not always.

If this statement seems lukewarm about democratic reform, it shouldn’t. The institutions that make decisions about broad questions of distributive justice are badly undemocratic, and changing that situation is a fundamental task of our time. I just wouldn’t interpret it to mean that all organizations must become democratic, because if they did, I would want to leave them.

(National Airport) What defines an “organization”? Normally, I would cite some kind of boundary around the people who belong to the group, plus some kind of system for making decisions that affect the whole. The boundaries can be temporary or permeable, and the decisions can be partial or occasional, but these seem to be definitive features.

It’s interesting to think about the global community of Buddhist monks, the sangha. According to the received story, The Buddha himself ordained the first monks and nuns and gave them the authority to ordain others. According to this account, today’s Buddhist monastics are descendants of a continuous series of ordinations that go back to the founding; this makes them the sangha. There are strict criteria for membership, and new monks and nuns take detailed vows. Even if the lineage of ordinations doesn’t really extend from each of today’s monastics all the way back to The Buddha, the lines extend a long way through history, and the story makes a plausible hypothetical.

The sangha is clearly a network, because the ties of ordination link everyone. Is it also an organization? It has a boundary (with monks/nuns on the inside and laypeople without). The ordination criteria and vows are tools for constraining the monastics’ behavior and influencing results. A monk can be expelled by his own abbot. Because there is no leader, steering committee, or electorate, it is hard to change the direction of the sangha as a whole (as opposed to the policies of any given monastery). But the practices of the whole sangha can evolve as a result of the members’ aggregate choices. Practices could shift quickly if a change that was compatible with the traditional vows spread fast. Is that enough to make the sangha an organization?

Incidentally, priests in the Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Eastern Orthodox churches all claim a lineage of ordinations all the way back to Jesus and St. Peter—the Apostolic Succession. So do some Lutherans, Methodists, and Moravians. If the global Buddhist sangha is an organization, then all of these churches also form one organization that just happens to be internally divided today. I think that is more or less the Anglican view of the situation, but not the Roman Catholic one; and the other denominations are mixed on the issue. This raises the question of whether someone can be a member of a given organization and yet deny it.