(Providence, RI) What makes us think that certain features of objects are integral or essential while others are optional? For instance, a banana could be straight and still a banana, but a wheel must be round to be a wheel. You could change the material of a wheel without changing its status, but you cannot make a (real) banana out of something other than a certain kind of fruity flesh.

This is a psychological point and not a logical or metaphysical one. People will differ in what they consider definitive about a banana, and many (or even all) of us could be wrong. But we tend to think of some aspects of objects as central and essential, and others as optional. We can develop models that mimic–and help elucidate–how people make those distinctions.

These models interest me not so much when applied to everyday objects like bananas and wheels, but when turned toward matters relevant to human values. For instance, what makes us assign a person to a “culture”? (Cultures have many features, and they always encompass much internal diversity, yet we confidently declare that individuals represent particular cultures.) Likewise, when do we assign a person to a moral category, such as “liberal” or “religious”?

Sloman, Love, and Ahn* ask subjects various questions about what features of an ordinary object, such as an apple, are integral to it. For instance, surprise: How surprised would you be to find an apple that had no skin, that did not grow on a tree, or that was blue? Salience: How prominent in your conception of an apple is that it is edible, or red, or round? Inference: If you knew that something grew on trees, would you guess that it was edible, round, or red?

The authors develop a statistical model that can predict which features of an object are seen as most integral. The model turns out to depend on the survey questions about mutability. We define an object by the kinds of features we think can’t be changed. These features compose its identity, as we perceive it. (Again, this is a psychological finding and not a logical or metaphysical one.)

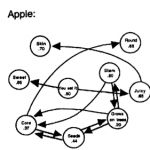

The authors then argue that what makes a feature seem immutable is the degree to which other features seem to depend on it. That leads to a second experiment in which the features of an object are scattered on a piece of paper and subjects are asked to draw lines between the features that they consider dependent on each other . For example, this graph shows an arrow between two features of an apple: “sweet” and “you eat it.” Apparently, we eat apples because they are sweet. Overall, the graph reveals two connected subnetworks, one concerned with apples as food and the other with the apple’s reproductive history (p. 223).

. For example, this graph shows an arrow between two features of an apple: “sweet” and “you eat it.” Apparently, we eat apples because they are sweet. Overall, the graph reveals two connected subnetworks, one concerned with apples as food and the other with the apple’s reproductive history (p. 223).

Of course, the image above is not a representation of an apple. It does not depict or convey the juicy crunch of the real fruit. Nor would it define an apple as objectively as, say, a DNA sequence. It doesn’t provide necessary and sufficient conditions for being an apple. It is rather a representation of the everyday mental model that subjects use in classifying objects as apples.

Now consider what happens when we introspect and assign ourselves to normative categories. Even if I limit my introspection to ethical matters, I observe many features of my own thought: principles, methods, aversions, enthusiasms, commitments, loyalties, open questions. Some of these I consider quite optional and superficial. If I changed those opinions, I wouldn’t believe that I had changed. Others seem more fundamental, so that I doubt that I could change them at all, and if I did, I would be someone new.

The model from Sloman, Love, and Ahn suggests a way of distinguishing between superficial and fundamental commitments. The fundamental ideas have many dependent ideas, so that if they change, it starts a whole chain of other changes.

Of course, people can differ in the degree to which their worldviews depend on just a few ideas, and therefore how much change any shift will cause. Some people organize their moral thought systematically, so that it all depends on a few premises (or even one sumum bonum). Others are not able to systematize in that way, or object to doing so. John Keats, for example, defined “Negative Capability” as the capacity not to organize one’s thought so that it was dependent on any particular ideas. He attributed that capacity to Shakespeare and also to himself, writing, “it is a very fact that not one word I ever utter can be taken for granted as an opinion growing out of my identical nature [i.e., my identity].” He implied that he could change any given idea without much effect on the whole of his thought, whereas people like Coleridge built their whole mentalities on narrow foundations.

The model from Sloman et al. suggests this is difference is a matter of degree. Probably all of us fall on the spectrum somewhere between Keats and, say, Jeremy Bentham. The network model is flexible enough to depict anyone.

*Steven Sloman, Bradley C. Love, and Woo-Kyoung Ahn, “Feature Centrality and Conceptual Coherence,” Cognitive Science, vol. 22, no. 2 (1998), pp. 189-223.

See also: “the politics of negative capability“; “toward a theory of moral learning“; and “a different take on coherence in ethics.”

(Dallas) I’m getting ready to present at the League of Women Voters’ annual meeting, which offers all the traditional trappings of a reform conference in the US: proud banners for each state’s delegation, canvassers standing at the door with flyers, tote bags with the League’s logo.

(Dallas) I’m getting ready to present at the League of Women Voters’ annual meeting, which offers all the traditional trappings of a reform conference in the US: proud banners for each state’s delegation, canvassers standing at the door with flyers, tote bags with the League’s logo.