- Facebook986

- Total 986

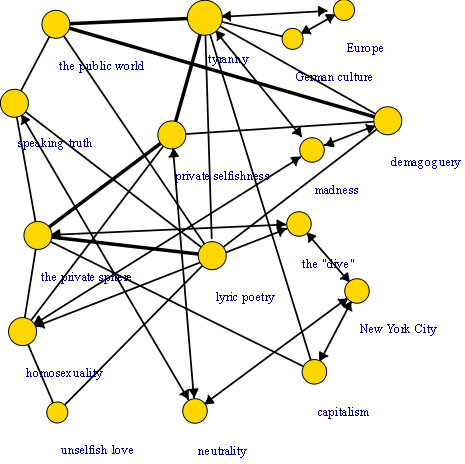

A moral worldview is a set of beliefs or values connected by various kinds of relationships. For instance, one belief may imply another, or may subsume another, or may be in tension with another even though both are truths. If analyzed that way, a whole worldview can be mapped as a network, with the beliefs viewed as nodes, and the relationships as ties.

Using that method, we can map the moral network implied by a work of literature, such as a lyric poem. Previously, I wrote some notes on W.H. Auden’s poem “September 1, 1939” (notes here; full text here.) I then mapped the moral network of that work. I think my first effort was a bit off, so here is a revised map:

What assumptions underlie this method?

1. The moral evaluation of literature is a valid and useful mode of criticism. It is not just about judging the values of the text (pro or con), nor is it merely a matter of elucidating what the author meant or what the text implies about moral issues. It is rather a critical engagement with the moral perspective of the work, a kind of joint investigation into what is really good and right that is informed by both the text and the reader’s critical response. Although I think that remains a rare mode of literary criticism, it has prominent defenders.*

2. Formal network analysis, a branch of graph theory, offers insights about the structure of any system that is composed of objects and relationships. Tools from network analysis, such as calculating the centrality of nodes or the density of relationships, can help to elucidate and assess the moral worldview of a work of literature.

Underlying this premise is a deeper assumption that moral worldviews should not be assessed only (or mainly?) by evaluating the correspondence between their separate ideas and truths about the world. It’s also (or more?) important to ask how the whole worldview hangs together. The question is not whether Auden should be against tyranny, but how that stance fits into his overall thinking. When people argue for assessing a whole worldview instead of individual principles, their next step is usually to look for internal consistency. But consistency is not the main virtue of a well-structured worldview. Better a mentality that incorporates valid and fruitful tensions than one that avoids all inconsistencies at the cost of narrowness or oversimplification.** Network analysis reveals density and other virtues that are more helpful than consistency. (See also “ethical reasoning as a scale-free network.”)

3. Abstract and general principles are overrated. I do not claim that they should be expunged from one’s moral thinking (that would be an over-radical form of “particularism”), but rather that there is no good reason to assume that a well-ordered moral mentality can be arranged like an organizational chart, with the abstract principles at the top and all one’s concrete beliefs and commitments as mere implications. That would be one kind of moral network map, and some people do think that way. Other people are much more concrete, or they mix concrete particularities with abstract generalities in interesting and complex networks. For instance, I think New York City and the “dive” bar where Auden sits in this poem are just as important to his moral vision as tyranny or selfishness.

One reason not to try to make the abstract principles fundamental to one’s whole network is that certain crucial ideas, such as love, will then be distorted. These ideas have the feature that they are sometimes good and sometimes bad, depending on the circumstances. If you try to organize your thinking around abstract and general principles, you will be compelled to divide love into the good and bad kinds, and that is false to the experience of what love is.***

Turning the map above back into a written analysis of “Sept 1, 1939” would take some space, but I think a few key points emerge:

- Auden has a dense moral network, not dependent on just one or two ideas. It’s robust. For instance, he later came to hate the line, “We must love one another or die.” But the poem does not rest on that.

- Love, art, and politics are densely interconnected.

- Homosexuality is not mentioned in the poem but is alluded to at least twice. It is hard to know whether Auden would connect it to “unselfish love.” I would. So I am either in disagreement with the poem or sympathetic with Auden (a gay man in the 1930s) because he could not draw that connection openly.

- Much depends on a polarity between public and private, but poetry occupies an uneasy space between. Consider declamatory statements like this: “There is no such thing as the State / And no one exists alone.” Are they incursions of public demagoguery into a poem, which should be private? Or should the poem speak truth to power?

*See David Parker, Ethics, Theory and the Novel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994); Todd F. Davis and Kenneth Womack, Mapping the Ethical Turn: A Reader in Ethics, Culture, and Literary Theory (Charlottesville, University Press of Virginia, 2001), Amanda Anderson, The Way We Argue Now: A Study in the Cultures of Theory (Princeton, 2006)

** Simon Blackburn, “Securing the Nots,” in W. Sinnott-Armstrong and M Timmons, eds., Moral Knowledge (New York, Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 95

*** This is basically my thesis in Reforming the Humanities: Literature and Ethics from Dante through Modern Times (Palgrave Macmillan, December 2009).