I’m at Boston’s Logan airport, waiting to fly to DC for a day’s meetings. Then we’re going on vacation for a week, and I will try to stay offline as much as I can. So no blogging until July 5 or so.

Monthly Archives: June 2011

economic benefits of civic engagement

- Facebook410

- Total 410

Does civic engagement (or you can call it “democratic participation,” or “stronger civil society”) help communities economically? I don’t think there is a large literature on that question, at least with explicit reference to the United States. Of course, wealthier communities tend to be more engaged, but that could be because income and other assets make engagement easier. It is trickier to detect a causal arrow that points in the opposite direction. However, based on the sources listed below, I would make the following hypothesis: the quality–not the quantity–of civic engagement is related to whether communities can withstand economic crises and make difficult collective decisions that help them to recover.

- Vaughn L. Grisham’s, Tupelo: The Evolution of a Community, which associates the remarkable economic success of Tupelo, Miss, with its civic infrastructure.

- Sean Safford, “Why the Garden Club Couldn’t Save Youngstown: Civic infrastructure and mobilization in economic crises,” which emphasizes differences in network structures, not raw amounts of engagement.

- Jeffrey Berry, Kent Portney, and Ken Thomson, The Rebirth of Urban Democracy, which shows that cities with stronger associational participation are able to make difficult decisions better.

If I am missing research or plausible hypotheses, I would love to know.

the truth of focus groups and surveys

- Facebook288

- Total 288

I am deep into coding focus groups, along with my colleagues at CIRCLE. We have convened working-class, urban youth in several American cities. We listen to audio recordings of their discussions with the software package called NVivo and, in addition to making open-ended notes, we attempt to categorize individuals’ statements into one of several hundred codes that we have constructed.

Often, what you hear is not a belief, a preference, or a principle. It is the sound of someone thinking about and around a topic that he or she may never have considered before. Asked whether voting makes a difference, for example, an individual may give a short monologue that drifts between yes and no and then back again, passing by way of such ideas as “no, but you should do it anyway,” and “yes, but only if other people do it, too.”

This reminds me of Nina Eliasoph’s comments from Avoiding Politics (p. 18):

Research on inner beliefs, ideologies, and values is usually based on surveys, which ask people questions about which they may never have thought, and most likely have never discussed. … The researcher analyzing survey responses must then read political motives and understandings back into the responses, trying to reconstruct the private mental processes the interviewee ‘must have’ undergone to reach a response. That type of research would more aptly be called private opinion research, since it attempts to bypass the social nature of opinions, and tries to wrench the personally embodied, sociable display of opinions away from the opinions themselves. But in everyday life, opinions always come in a form: flippant, ironic, anxious, determined, abstractly distant, earnest, engaged, effortful. And they always come in a context–a bar, a charity group, a family, a picket–that implicitly invites or discourages debate.

That’s why the qualitative research we are doing now is interesting. And yet, there is a different way of thinking about people’s mental states and the relationship to their actions. It turns out (from a study of ethics rather than our topic, politics) that people “have a hard time offering an account of their moral reasoning that contains consistent substantive content.” They are “largely incapable of articulating their moral decision-making process in substantive, propositional terms.” Often, their responses to open-ended questions are rationalizations of what they have done, not reasons that will guide what they do.*

A cynic would conclude that people are just not very reasonable; our principles and reasons do not affect our behavior. But it turns out that individuals answer multiple-choice questions in ways that are consistent with their own responses; distinctive, when compared to other respondents; and strongly predictive of their own behavior. In other words, we are guided by something that’s in our heads, and it differs from person to person, but it is not linguistic or explicit. It is more like an unconscious network of associations. That is why fixed-response or “multiple choice” surveys often predict behavior better than open-ended questions do. They may work better for prediction because an actual decision (such as whether or not to vote) is more like checking a box than explaining a personal philosophy. So answering the forced choices on a survey resembles our ordinary decision-making process.*

Yet I remain interested in people’s explicit, verbalized, public thinking. We ought to give good reasons to justify (or criticize) our own actions. We should be interested in other people’s reasons and their reactions to ours. The act of interpreting the public thoughts of working-class urban youth thus has a moral motivation, even if those reasons are not strongly influential in their own lives. I don’t think that current psychological research precludes the hope that good arguments can change people’s implicit stances or premises, which then affect their behaviors.

In short, we should strive to understand other people’s arguments in case they are right and to decide how to respond effectively if they are not.

*Stephen Vaisey, “Motivation and Justification: A Dual-Process Model of Culture in Action,” The American Journal of Sociology, vol. 114, no 6 (may 2009), pp. 1675-1714.

could the president pivot to anti-corruption?

- Facebook322

- Total 322

Based on recent polling, Andrew Levison argues that a minority of Americans (call them the supply-siders) believe that a combination of federal spending cuts and tax cuts would boost the economy. A different minority (the Keynesians) believe that federal spending increases would help people economically. But a significant third group remains undecided. For them, the issue is not whether government programs could stimulate the economy and create jobs. The issue is whether government would succeed, given its (perceived) incompetence and corruption. A lot of people believe these statements, drawn from focus groups:

“Government can’t really solve problems. It always screws up anything it does. It can throw money around, but that’s about it.”

“The politicians in Washington don’t give the slightest damn about people like me. They take care of their fat-cat contributors and big business lobbyists and sell the average person down the river every chance they get.”

I sort of tend to believe these points myself–which is why I spent two years of the 1990s working for Common Cause and wrote a book about political reform–and my doubts have been reinforced by the way Congress responded to the financial crisis. Thus, for substantive rather than merely political reasons, I’d favor making corruption a major issue from now on in the Obama administration. And I would define corruption as the influence of money on policy.

The question is whether President Obama could make corruption his theme at this point–with any credibility and any chance of success. It would not be easy, but he did have a pretty strong record in both Illinois and the US Senate. During the presidential primary season, he regularly attacked lobbyists and Political Action Committees and saw “the issue as a bright line [between himself and] Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton.” I cannot find evidence now, but I am pretty sure that he and Clinton argued about campaign finance inside the Senate Democratic caucus, with Obama taking the pro-reform position.

In the general election, I thought his campaign soft-peddled corruption somewhat, and I would attribute that decision to several factors:

- A lot of “base” Democratic voters believed that the cause of corruption lay solely with Republicans, so defeating them in a national election would end the problem. Addressing the underlying causes of corruption was unnecessary to motivate these base voters.

- Incumbent Democratic elected officials did not want serious reforms and would have thrown up obstacles.

- The Obama people believed that a combination of better transparency and more small donations over the Internet would actually mitigate corruption–beliefs with which I happen to disagree.

- “Process” issues like campaign finance reform were much less urgent in the middle of an economic free-fall than the stimulus package and health reform. The strategy was to pass those bills despite special-interest pressure.

All those factors make the lack of attention to political reform at least forgivable. But the result was wasteful economic policy that benefited banks and rich taxpayers more than it had to; and now the whole federal policy agenda has stalled.

After Obama was elected, the Supreme Court made the situation starkly worse with the Citizens United decision that legalized campaign contributions by corporations. Whether because of Citizens United or for other reasons, the amount of private money spent on elections quintupled between 2006 and 2010 (successive midterm years).

Citizens United creates a rhetorical opening for the president. Even though the majority didn’t exactly say that corporations are persons (they rather cited corporations as associations under the First Amendment and treated money as speech), the decision is certainly unpopular–and for good reasons. Besides, from a narrowly partisan perspective, it’s easier for a Democratic president to attack the funding perquisites of Congress when the House happens to be in Republican hands.

Thus I think the President has an opportunity to say: “I have always criticized wealthy special interests and fought for reform. I chose not to make campaign reform my first priority when I entered the White House in the middle of an economic collapse, but now I think that was a mistake. I didn’t fully grasp the insidious power of money and how it frustrates our efforts to restore the real, working economy of America. In any case, now that the Supreme Court says that corporations can give unlimited money to candidates to get the policies they want, I realize this is our number-one issue. It’s a precondition for making the government work for people, not for rich interests.”

The next question is what he would actually fight for. I would recommend a Constitutional Amendment for campaign finance reform, not as a panacea, but as a helpful policy that would also send a strong public message that government and the market are two different spheres and that money is problematic in politics. Wealthy interests will always have disproportionate political power, but that does not mean that their deliberate efforts are respectable. Money is not speech, lobbies are not civil society, and corporate pressure is not “government relations.” Restoring these elements of our traditional public philosophy would put some constraints on the most egregious behavior.

the public wants us to teach facts, not skills of citizenship

- Facebook40

- Total 40

A perfect citizen would know an enormous range of facts, concepts, and skills, from macroeconomics to how to chair a meeting, from the contents of the Federalist Papers to the principles of statistics. (See my list in this HuffingtonPost article.) In practice, schools must decide what is most important to teach in the limited hours available to them. I value facts about politics and government and related academic concepts, but my highest priority would be the arts and habits of association that De Tocqueville thought were the basis of successful democracy in America. Unless citizens can successfully manage projects and groups, we are left to the mercies of the state and market. Further, by co-managing our own associations, we develop reasonable ideas about how to address larger public issues.

I find good news and bad news in a new American Enterprise Institute report entitled Contested Curriculum: How Teachers and Citizens View Civics Education. Good news: teachers, especially in public schools, generally share my goals and priorities. Bad news: American citizens do not.

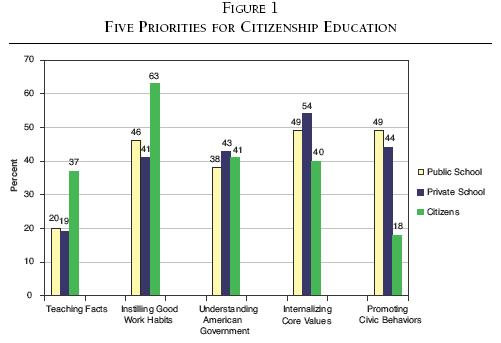

In the following graph, snipped from that report, “Public School” means the opinions of social studies teachers in public schools. “Private School” refers to social studies teachers in private schools. “Citizens” means a representative sample of 1,000 adult Americans. The bars bear simplified labels. For example, “Teaching facts” is short for: “It is absolutely essential [for students] to know facts (e.g., the location of the 50 states) and dates (e.g., Pearl Harbor).”

Look at the last cluster of columns, showing that while teachers think it is important to promote civic behaviors, citizens do not.

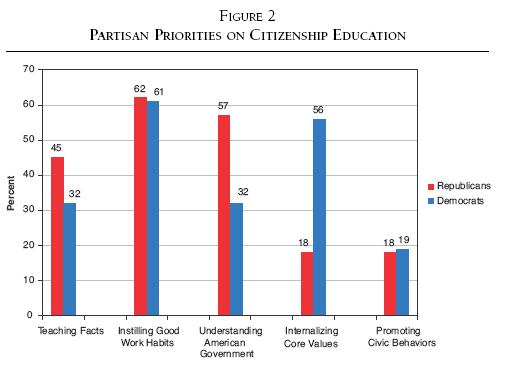

That first graph reveals one political obstacle for people who share my priorities: we are in the minority. Another–equally familiar–problem is the partisan split. Basically, Republicans are considerably more supportive of facts and academic concepts than Democrats are. But Democrats are more sympathetic to values. For instance, teaching students “To be tolerant of people and groups who are different from themselves” (one component of the bar shown below as “Internalizing core values”) seems “absolutely essential” to 31% of Republicans and 69% of Democrats.

Standards (official guidelines for what should be taught) tend to include all of the above priorities. That is the path of least resistance for policymakers: just add everything to the list. But the emphasis in classrooms is not determined by standards; it is much more shaped by tests. To the extent that states require tests of civics, almost all the content involves facts and academic principles.

In short, citizens, and especially Republican citizens, are getting an educational policy closer to what they want than to what teachers (and I) would prefer.