Civil society is increasingly dominated by people who have received relevant professional training or who officially represent firms and other organizations. In local discussions about schools, for example, a significant proportion of the participants may hold degrees in education, law, or a social science discipline or represent the school system, the teacher’s union, or specific companies and interest groups.

Such people can contribute valuable sophistication and expertise. But if my arguments here are correct, we should not be satisfied with public discourse that is merely technical or that reflects negotiations among professional representatives of interest groups. We should want broad deliberations, rooted in everyday experience, drawing on personal experience and values as well as facts and interests, and resistant to the generalizations of both professionals and ideologues.

Technically trained professionals already intervened powerfully in public policy and institutions a century ago. The ratio of professionals in the United States doubled between 1870 and 1890, as society became more complex and urbanized and scientific methods proved their value. More than 200 different learned societies were founded in the same two decades, and learned professionals specialized. For example, physicians split into specializations in that period. The historian Robert L. Buroker deftly describes the implications for politics and civic life: “By 1900 a social class based on specialized expertise had become numerous and influential enough to come into its own as a political force. Educated to provide rational answers to specific problems and oriented by training if not by inclination toward public service, they sensed their own stake in the stability of the new society, which increasingly depended upon their skills.” At best, they offered effective solutions to grave social problems. At worst, they arrogantly tried to suppress other views. For instance, the American Political Science Association’s Committee of Seven’s argued in 1914 that citizens “should learn humility in the face of expertise.”

One of the great issues of the day became the proper roles of expertise, specialization, science, and professionalism in a democracy. The great German sociologist Max Weber interpreted modernity as a profound and unstoppable shift toward scientific reasoning, specialization, and division of labor. One of Weber’s most prominent students, Robert Michels, introduced the Iron Law of Oligarchy, according to which every organization–even a democratic workers’ party–would inevitably be taken over by a small group of especially committed, trained, and skillful leaders. In America, the columnist Walter Lippmann argued that ordinary citizens had been eclipsed because of science and mass communications and could, at most, render occasional judgments about a government of experts. Thomas McCarthy, author of the Wisconsin Idea, asserted that the people could still rule through periodical elections, but expert managers should run the government in between. John Dewey and Jane Addams (in different ways) asserted that the lay public must and could regain its voice, but they struggled to explain how.

Thus the contours of the debate were established by 1910. If dominance by experts is a problem, it was already evident then. But even if the conceptual issue (the role of specialized expertise in a democracy) is the same today as it was in 1900, the sheer numbers are totally different. This is a case in which quantitative change makes a qualitative difference.

Just before the Second World War, the Census counted just one percent of Americans as “professional, technical, and kindred workers”: people who according to, Steven Brint’s definition, “earn[ed] at least a middling income from the application of a relatively complex body of knowledge.” This thin slice of the population was spread fairly evenly. There was usually a maximum of one “professional” per household, and even in a neighborhood association or civic group, there might just be one physician, one lawyer, and one person with scientific training. Often these people (mostly men) had been socialized into an ethic of service. They had valuable specialized insights to offer, but they were obliged to collaborate with non-experts on an almost daily basis to get anything done. Without romanticizing the relationship between professionals and their fellow citizens, I would propose that the dialogue was close and reciprocal.

Today, in contrast, there are so many “professionals” (and they are so geographically concentrated) that particular neighborhoods, and even whole metropolitan areas, can be dominated by people who make a good living by applying specialized intellectual techniques. As holders of professional degrees, these people possess markers of high social status that were much more ambiguous a century ago, when gentlemen were still expected to pursue the liberal arts, and the professions still smacked slightly of trades. When wealthier and more influential communities are numerically dominated by people with strong and confident identities as experts, the nature of political conversation is bound to change.

In 1952, of all Americans who said that they had attended a “political meeting,” only about one quarter held managerial or professional jobs. Many more (41 percent) worked in other occupational categories: clerical, sales and service jobs, laborers and farmers. The rest were mostly female homemakers. In short, professionals and managers—people trained to provide specialized, rational answers to problems—were outnumbered three-to-one in the nation’s political meetings. By 2004, however, 44 percent of people who attended political meetings worked in managerial or professional occupations, and 48.5 percent held other jobs. The ratio nationally was now almost even, and professionals were the dominant group in affluent communities.

These are crude categories that do not tell us how people talk in meetings. A clerical worker could argue like a technocrat; a physician could tell rich, personal stories, laden with values. But I think the increasing proportion of professionals and managers in our meetings tells a story about a society dominated by people with specialized training and expertise.

Theda Skocpol notes that traditional fraternal associations like the Lions and the Elks, which once gathered people at the local level who were diverse in terms of class and occupation (although segregated by race and gender), have lost their college-educated members. But non-college-educated or working class people remain just as likely to join these groups. It is not so much that working-class people have left civic groups, but that professionals have left them–moving from economically diverse local associations to specialized organizations for their own professions and industries.

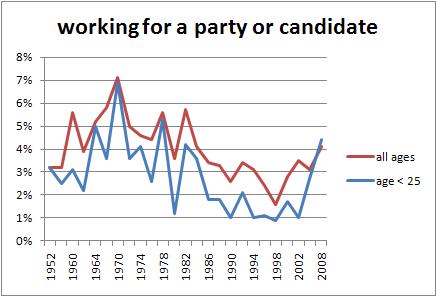

The proportion of all Americans who are professionals or managers has roughly doubled since the 1950s. That is a benign shift in our workforce, reflecting better education and more interesting jobs. It largely explains why highly educated specialists have become more numerous in meetings. They bring sophistication and expertise to community affairs. Still, two thirds of people do not classify themselves as professional or managers, and it important for their values and interests to be represented. The steep decline in traditional civil society leaves them poorly represented, to their cost and to the detriment of public deliberation.

[works cited here: Burton Bledstein, The Culture of Professionalism (New York, 1976), pp. 84-6; Robert L. Buroker, “From Voluntary Association to Welfare State: The Illinois Immigrants’ Protective League, 1908-1926,” The Journal of American History, vol. 58, no. 3 (Dec, 1971), p. 652; APSA Committee of Seven (1914, p. 263, quoted in Stephen T. Leonard, “‘Pure Futility and Waste’: Academic Political Science and Civic Education,” PSOnline (December 1999); Steven Brint, In an Age of Experts, The Changing Role of Professionals in Politics and Public Life (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), p. 3; Theda Skocpol, Diminished Democracy: From Membership to Management in American Civic Life (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003), pp. 186-7. Statistics on political meeting participation are my own results from the American National Election Studies.]