Yesterday, 6:00 am: In a dark house with a sleeping family, unable to rest myself, I’m working on a proposal to the National Science Foundation.

8:30 am: The Metro train is jammed because everyone is large in their winter coats. It’s too tight for newspapers, so people stare vacantly at one another.

9:30 am: In a conference room on K Street, overlooking a square with trees that are sugared by the season’s first snow. Bright light streams through the huge panes. Eight people sit around a large conference table talking about the appropriate “message” for a nonpartisan political campaign. The short speeches begin with self-deprecating jokes, but everyone seems fundamentally self-assured and experienced.

11:30 am: In another conference room, 6.5 miles northeast of K Street. This one is windowless and crowded. The walls are decorated with binders. We are going over the budget of a nonprofit organization. The institution itself is prospering, but the broader trends–lots of kids to serve, impending cuts in federal spending–make us sober.

4:00 pm: In our front yard with our 6-year-old, building a foot-high “snowman” out of powdery snow as the clear sky turns dark blue behind a lattice of tree limbs. Venus and a slender moon appear over the roofs; commuters crunch home.

10:00 pm: Back to the NSF proposal and email, but there’s time for cookie and tea with my wife and teenager and then a few pages of Orhan Pamuk’s My Name is Red.

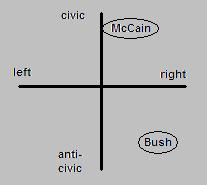

I suspect that McCain would improve our civic condition. I do not say that because I know that he is a wonderful person. (I am against hero-worship as a matter of principle, and I distrust judgments of character mediated by reporters.) I say it because improving the quality of public life–like any serious political endeavor–requires spending energy and capital, thinking tactically, and confronting opponents. Civic reform would be McCain’s strongest suit; therefore, he would be smart to make it a genuine priority.

I suspect that McCain would improve our civic condition. I do not say that because I know that he is a wonderful person. (I am against hero-worship as a matter of principle, and I distrust judgments of character mediated by reporters.) I say it because improving the quality of public life–like any serious political endeavor–requires spending energy and capital, thinking tactically, and confronting opponents. Civic reform would be McCain’s strongest suit; therefore, he would be smart to make it a genuine priority.